Book review: Dispatches from the Front brings a legendary war reporter to life

New biography of Matthew Halton is “scrupulously even-handed.”

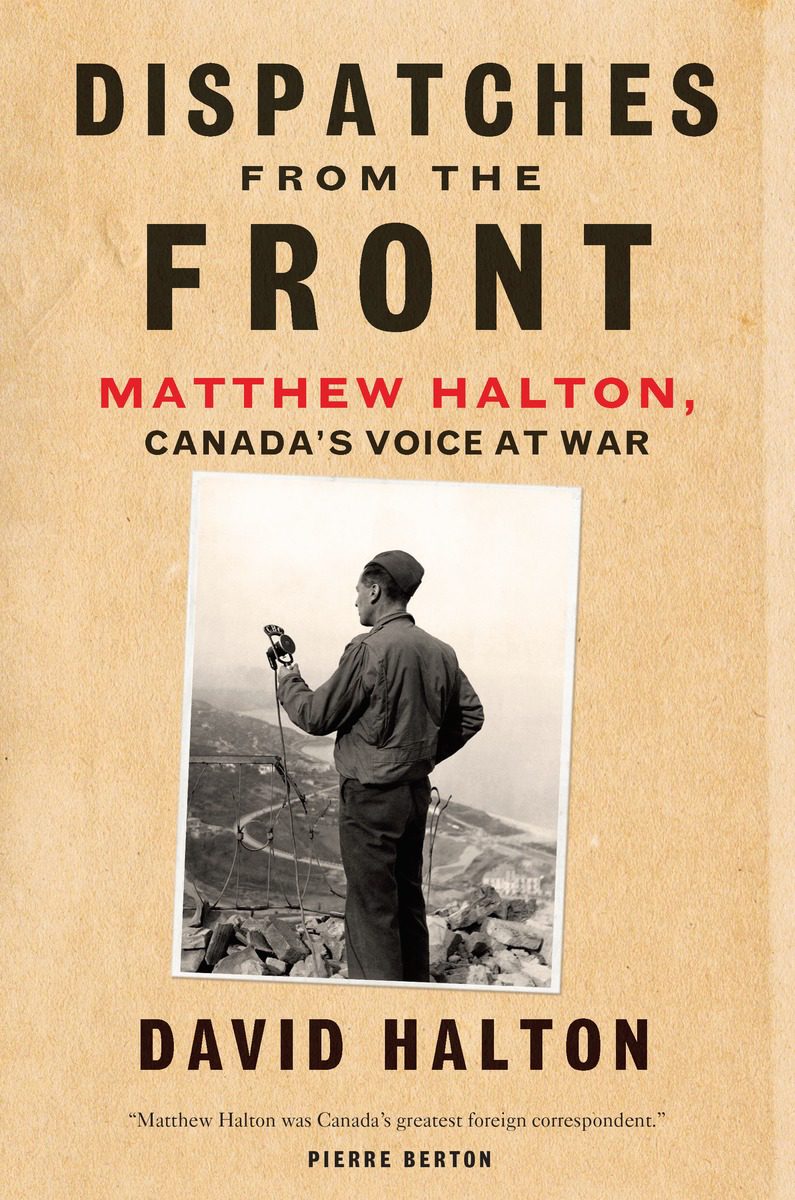

David Halton, Dispatches from the Front: Matthew Halton, Canada’s Voice at War (McClelland & Stewart, 2014). Cloth, $34.95.

By Gene Allen

Most Canadians—other than those who were actually members of the armed forces—experienced the Second World War primarily through the news media. Canada’s military, like that of other Allied nations, realized that civilian support for the war required a steady flow of news about the exploits of Canada’s soldiers, sailors and flyers. Unlike in the First World War, journalists were seen, according to the army’s “Regulations for Press Representatives with the Canadian Army in the United Kingdom” in May 1941, as “as valued colleagues with [[{“fid”:”3486″,”view_mode”:”default”,”fields”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:””},”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”attributes”:{“height”:”1200″,”width”:”795″,”style”:”width: 200px; height: 302px; margin-right: 12px; margin-left: 12px; float: right;”,”class”:”media-element file-default”}}]]a most important mission to discharge. They will be fully trusted, treated with complete frankness and given every proper facility for their work.” While the application of military censorship placed significant limits on what could and could not be reported, newspaper readers and radio listeners followed Canada’s participation in the war on a daily and even hourly basis, bringing an unprecedented common focus on the nation at war.

The most important of the institutions that provided this steady diet of war coverage were The Canadian Press news agency and the much more recently established Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (an astonishing 86 per cent of adult English-Canadian radio listeners tuned in to the CBC’s war news every night). And none of the CBC’s correspondents was more prominent than Matthew Halton. Along with Peter Stursberg, Marcel Ouimet and others, Halton brought Canadians into daily contact with the battles of the Sicilian and Italian campaigns, D-Day, the liberation of France and the Netherlands and Germany’s eventual surrender. For 10 years before joining the CBC in 1943, Halton also covered the rise of Nazism—he was one of the earliest and most consistent critics of Hitler in the 1930s—and the early years of the war, including Dunkirk, the London blitz and the North African campaign, as European correspondent of the Toronto Star.

In this biography by Matthew Halton’s son, David—himself a highly respected CBC journalist, with postings in Ottawa, London, Paris, Moscow and Washington over a 40-year career—Matthew’s war coverage for the CBC takes pride of place, as the title suggests. David provides a gripping and detailed account of the stories that Matthew covered—including the bloody siege of Ortona, Italy, the brutal first weeks of the 1944 Normandy campaign, the liberation of Paris, the Nazi surrender in Berlin—and how he covered them. David captures Matthew’s unique editorial voice, with extensive quotations from his moving and literate (and, in the words of his close friend and fellow correspondent Charles Lynch, sometimes “flowery”) reports.

Unlike some correspondents who stayed near the press camp, Matthew insisted on getting as close as possible to the front lines, sometimes coming under enemy artillery fire. The power of Matthew’s coverage (even though he estimated that censorship prevented him from reporting on 40 per cent of what he saw, and the details of a further 20 per cent were too horrible to be reported) made him a major celebrity in Canada and gave him an international reputation when his reports were carried on the BBC and in the United States.

Giving a warts-and-all picture of one’s subject can be a challenge for any biographer, especially for a son whose avowed purpose in writing is to “re-awaken interest in a Canadian legend.” But David, relying on an extensive and frank collection of letters between Matthew and his wife, Jean, his diaries and interviews with contemporaries, is scrupulously even-handed. Matthew’s great abilities and achievements went along with some major personal weaknesses, notably a chronic over-reliance on alcohol and a series of poorly concealed extra-marital liaisons, especially when he was on his own in London during the war. Still, David concludes that the drinking and the affairs “appeared to have had no effect on a marriage that all their closest friends agreed was one of enduring love.”

Among his fellow correspondents, some considered Matthew standoffish and a snob, carried away by his own reputation—his determination to write poetry was unusual in those circles—while others enjoyed his company. After the war ended, Matthew struggled in his new role as the CBC’s chief European correspondent, undergoing “a slow descent from the summit of his career.” He died in 1956, only 52 years old, never regaining the fame and sense of accomplishment that his wartime role had brought.

This is an important, well-researched and highly readable book. (The story of Matthew’s role in the liberation of Paris, which included a passionate affair with a glamorous Resistance fighter, a well-lubricated and well-received impromptu speech before a crowd of 10,000 Parisians and being caught in a crossfire between rearguard Nazi supporters and French forces, reads like the script for an action movie.) Matthew Halton is undoubtedly a significant figure in the history of Canadian journalism, and David gives a judicious and convincing account of his contribution. My only regret was that I wanted to know more about his interactions with his editors and superiors at the Star and the CBC. Even larger-than-life individuals like Matthew Halton did their work in a context that was largely set by the institutions that employed them, promoted (and sometimes fired) them and encouraged them to go in some directions and not others.

[[{“fid”:”3487″,”view_mode”:”default”,”fields”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:””},”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”attributes”:{“height”:”500″,”width”:”667″,”style”:”width: 133px; height: 100px; float: left; margin: 12px;”,”class”:”media-element file-default”}}]]Gene Allen is a professor at Ryerson University’s School of Journalism. In 2013, he published Making National News: A History of Canadian Press.