Exploring the military-journalist relationship

By Leah Woolley for The Signal

Josie Lukey’s face is covered in mud, dirt, and dust. The sun is setting over Canadian Forces Base Wainwright in Denwood, Alberta and she’s standing on the hard leather seat of a tank, gripping its edge to stay upright. The vibrations of the engine echo through her body and make her teeth rattle. The tank crew’s radio communications are almost lost beneath the roar of the engine and the rush of wind blowing past her face. Behind the tank, only a trail of crushed foliage and muddy track marks remain. For Lukey, a journalism student in her final year at Calgary’s Mount Royal University, this tank ride is just one of many experiences in the April 2016 version of the Canadian Military Journalism Course (CMJC) in Calgary.

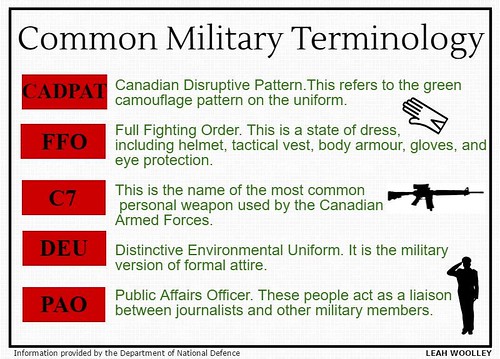

The annual course is run by Dr. Bob Bergen. He started out as a reporter in 1976; first for The Albertan, then for 20 years at the Calgary Herald. According to Bergen, the CMJC is meant to give young journalists access to the knowledge and experience he gained over his years of covering the Canadian Forces (CF). To start with, students are given more than 50 pages of military lingo to help familiarize them with more than 400 commonly used acronyms and initialisms. This is followed by 53 gigabytes of data detailing basic military information: rank structure, public affairs contacts, names and facts about weapons and vehicles, how Veterans Affairs works, how to use the Access to Information Act, and pertinent rules and regulations governing how military members can and can’t act. But do journalists really need to know all that? It’s a lot of information to learn.

Military Versus Media

At first glance, the military and the media seem irreconcilable. “It’s an oil and water mix. They both repel each other, by the very nature of the institutions,” says Scott Taylor, former CF infantry member and the author, editor, and publisher of Esprit De Corps magazine since 1988. “One is supposed to question everything, the other is supposed to obey unquestioningly.”

It’s an uneasy relationship, but a necessary one. Journalists are charged to keep watch over powerful players in society (politicians, corporations, and the wealthy, to name a few) – and the military is one of them. Besides that, the Canadian Forces is made up of 78,200 Canadian citizens. What they do and how they do it is important to know.

The 2011 National Household Survey conducted by Statistics Canada reported that 13,280 journalists are employed in Canada. The number of CF employees is almost six times larger.

How can journalists keep up?

“Quickly,” Taylor says. He disagrees with the notion that journalists might find the sheer size of the Canadian Forces – and the information that comes along with it – too challenging. “Journalists can quickly come up to speed,” Taylor says. He thinks that CMJC (he calls it “soldier camp”) is a little unrealistic, but emphasizes the importance of journalists being unafraid to question the military. “At the end of the day, if we’re putting these people in harm’s way, we need to be able to justify their sacrifice.”

Wanted: A Better Reputation

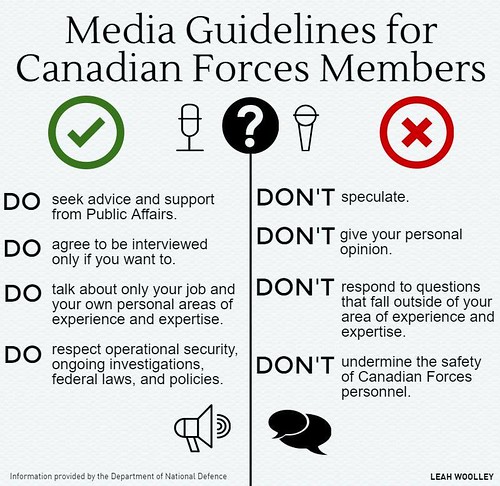

Journalists who learn quickly often first interact with Public Affairs. Captain Colette Brake is a Public Affairs Officer working in Royal Artillery Park in Halifax. She’s been with Public Affairs for eight years, and her main responsibility is to advise her commander on media relations. She also prepares soldiers for interviews and delivers media awareness training. All Canadian soldiers are required to receive media awareness training, which amounts to one 40-minute lecture per year. Brake says the training is supposed to make soldiers more comfortable with interacting with media. “I always tell them that journalists aren’t our enemy, but they aren’t our friends either.”

She says sometimes it can be difficult for soldiers to communicate with journalists because “we speak in a different language.” (Even between different military branches the lingo can be confusing.) Many soldiers also don’t like speaking to journalists because they must answer to a chain of command, Brake says. “They’re scared what they say will be written up in a way that will reflect negatively on them and get them in trouble with their supervisors.” She says soldiers who haven’t interacted much with the media often seem to think journalists are “out to get them.”

As both a journalist and a Canadian citizen, Noah Richler finds this response to journalism close-minded at best. In his opinion, when people talk about the difference between cultures and professions, they are creating excuses for not confronting or understanding different situations. “I would imagine that the sensible soldier understands the sensible journalist,” says Richler.

When soldiers say they hate journalists, it is criticism of a part expanded into criticism of the whole. “He or she has a particular incident in mind, and they’re blanket-charging the rest of journalists with it,” Richler says. “The soldier should not be free to go around elevating a culture in which journalists are categorically condemned.”

Richler agrees that there are great differences between soldiers and journalists, but rejects the idea that lack of experience with the military would negatively affect his understanding of soldiers. He maintains that education and learning are what is lacking in the relationship between the military and media. People must be willing to talk about something to understand it, he says. “What underpins our democracy as a whole is bright, vigorous discussion.”

Creating opportunities for discussion is part of the reason Bergen started teaching the CMJC. The course was founded in 2002, when the director of the Centre for Military, Security, and Strategic Studies approached Bergen for a discussion about how the Canadian press was covering the military badly. The centre is at the University of Calgary, so it made sense to pair up with Bergen, who was an adjunct assistant professor at the university and a well-seasoned journalist with experience in covering military stories. Bergen hoped that the CMJC would inspire more journalists to cover military stories, and says that, for the most part, it seems to be working.

Why It Matters

According to Bergen, coverage of military stories is becoming more important. Canada has been in seven wars since 1991, and before that had not been at war since the 1950s. That’s seven wars in the last 25 years. “That’s unheard of in Canadian history,” says Bergen. “The military application of force is more of a reality in the new millennium than it has been since the Korean Gulf War.”

Journalism schools, he believes, are not doing enough about it. “If you look at the Parliamentary Press Gallery in Ottawa, there’s more than 300 journalists there, and maybe about five or six of them know the difference between a Canadian Forces Corporal and a Polish Admiral.”

At least one school does cover the subject. The Bachelor of Journalism program at Carleton University offers a fourth-year elective called Journalism and Conflict. It covers topics such as the history of military reporting, practices of embedded journalism, journalists as witnesses, and the importance of objectivity, plus offers a field trip to a Canadian Forces base.

“We couldn’t offer a specialization in media and the military without offering other specializations as well,” says Susan Harada, Head of the Journalism Program and Associate Director of the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton. Other specialized courses for fourth-year students include arts and culture, sports, legal, political, and business.

Harada understands why there may be a lack of specialized journalism courses in other learning institutions. “There is very little room in a journalism program,” she says, “given all of the fundamental, foundational things that need to be taught.”

Harada would tell journalists looking for advice on military stories to make an effort to go in with a “clear understanding of the history and context with respect to the relationship between military and media.” CMJC has its uses, she says, but students still need the fundamental tools of reporting. Still, “someone who’s taken CMJC would be in a better position to report comfortably.”

Josie Lukey, our journalism student tank-traveller, agrees. She says CMJC is an effective starting point for students. “I knew nothing, and now I have a developed background in the terminology and all the different roles in the military. They’re like a whole community I didn’t know about.”

This story was first published on University of King’s College news site The Signal and is republished here with the author’s permission.

Leah Woolley studies Journalism and International Development at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia. After graduation, she hopes to focus on reporting stories from hard-to-reach places around the world. She is currently a reservist with the Canadian Armed Forces, a piano player, and that person who gets in trouble for reading books under their desk.