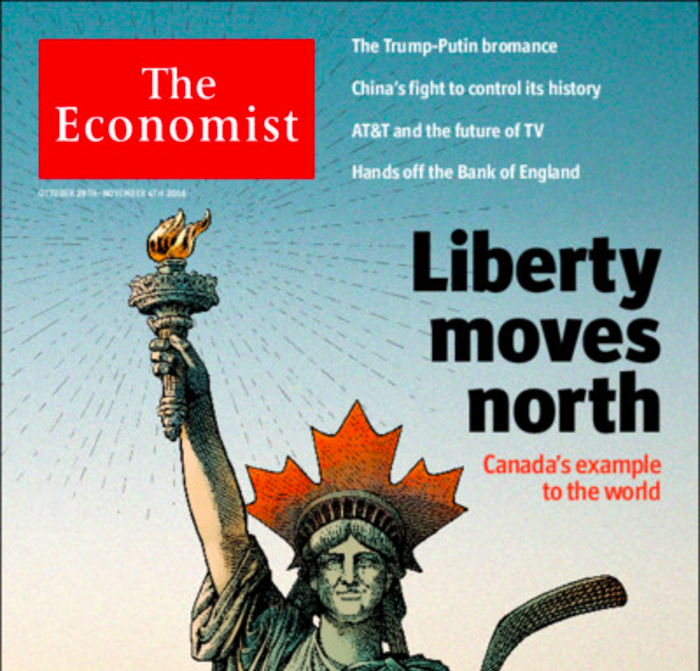

How Canada ended up on the cover of The Economist

By Madelaine Drohan

Reaction to the cover story I wrote for The Economist on Canada (Liberty Moves North, Oct. 29) revealed a lot of misconceptions about how such stories come about. Some pundits thought it was generated in London, making it a British view of Canada. Others went to the other extreme and said it was a Canadian view of Canada that just happened to appear in a British publication. Neither is correct. I thought it might be useful for my fellow journalists to describe how the process works.

Ninety-nine percent of the stories I’ve written for The Economist in 10 years as their Canada correspondent are the result of ideas I have pitched to the editors in London. At the end of every week I generally pitch two or three ideas I could write about the following week. The editors say yes, no or maybe, depending on whether there is a strong news peg and what else is happening in the world. The cover story was more of a hybrid.

For several months I had been discussing a piece on immigration and diversity with the editor of the Americas section, which is where Canadian stories appear. But while we were waiting for a news peg on which to hang the story, the editor of The Economist came up with a question that superseded that story. Why, she asked, was Canada not suffering from the same anti-immigration and anti-globalization protests that had led to Brexit in Britain, the rise of Donald Trump in the U.S., and populist movements in Europe?

That prompted the research that led to the cover story. It included a round of telephone interviews, some digging into history through academic papers and books, and then a round of face-to-face interviews, including one with the prime minister. The Americas editor came over from London and we travelled together to Winnipeg, Toronto and Montreal to interview people in person. We tried to get a broad range of views. We chose Winnipeg because it is in the centre of Canada but not Central Canada. If time and budget had allowed, we would have travelled farther west. Instead, westerners were interviewed by phone. The stringer in Vancouver happened to be visiting Nova Scotia, so sent a file from there.

At this point the story was already a British-Canadian project. The idea and central question came from London. My London-based editor participated in the bulk of the interviews and asked questions during those interviews that would only occur to someone looking at Canada from abroad. He helped place Canada in the global context. I wrote the first draft and sent it to him. We handed it back and forth several times before he decided it was ready for prime time or, in this case, the editor who handles the three-page briefings at The Economist.

Even at this stage, this level of editing far surpasses any I experienced in my previous incarnations as a foreign correspondent for the Globe and Mail, Ottawa correspondent for Maclean’s and the Financial Post and finance writer for The Canadian Press. Yes, most of those were published daily, or hourly in the case of The Canadian Press. I’m thinking here of how these media outlets treated lengthier, special projects when I was there. And this was not even the end of The Economist process.

The Economist holds at least two meetings a week which all London-based staff can attend: one on Monday to discuss which stories will appear in the print edition later in the week and one on Friday to discuss possible cover stories for the following week. I’ve only been to a few Monday meetings but suspect the Friday ones are broadly similar. Anyone in the room can voice an opinion on a piece, pointing out possible flaws or points to consider. The section editors defend their choices or agree on changes, which they then relay to whoever is writing the article.

So back to my piece, which is now with the editor who handles the three-page briefing notes. He has his own questions and also wants suggestions for illustrations in the form of photos and charts and graphs. (I had previously supplied interview audio and photos to the multimedia side of The Economist, but that is another story.) When the briefings editor is satisfied with the piece it goes to the fact-checker, one of a group of unsung heroes at The Economist. They go through every piece and check every fact.

Writers are supposed to supply sources (I do it by putting footnotes throughout the piece). Wherever possible, they should be primary sources. Newspaper articles and columns are not usually sufficient because few are fact checked. Wikipedia is definitely out as a source, because it can be unreliable, although it can be a useful place to start. If you use a fact in your piece that has no source, the fact checker will ask you for it. Wednesday, which is editing day for the print edition, can be a massive scramble for sources if you did not provide them to begin with. In 10 years I have written only one piece that did not elicit questions from the fact checker. It was very short.

The Economist is not finished with the piece yet. It starts to move up the chain of editors. Most of my regular pieces are also read by the foreign editor, who may have questions of his own. In the case of this cover story, it was read by the person editing the magazine that week.

While all this was going there was a parallel process for the editorial, or leader, as The Economist calls it. This was written by my immediate editor, who discussed it with me and debated it at an editorial meeting in London. It went through a separate editing and fact-checking process.

To call the piece a Canadian view or a British view is misleading. Both are ingredients in a complicated mix that eventually produces The Economist view.

The article and the leader represent the work and thinking of many people. That is one of the reasons why there are no bylines in The Economist. Having so many people weigh in does making writing such a piece more complicated. Yet the end result is worth it.

Madelaine Drohan is the Canada correspondent for The Economist. For the last 40 years, she has covered business and politics in Canada, Europe, Africa and Asia. In 2016, she became a senior fellow at the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa. In 2015-2016 she was the Prime Ministers of Canada fellow at the Public Policy Forum.