Suffering outside the headlines

It was evening when they suddenly heard gunshots.

Almaz Tilhun’s voice breaks as she brings up memories of the day her life changed dramatically, when she grabbed her six kids and fled.

Almaz and her family joined one million people who were displaced during conflict in Gedeo and West Guji zones in southern Ethiopia between April and July 2018. People were killed, houses burnt down, and livelihoods destroyed.

“We didn’t know what was going on. We looked outside and saw people fleeing when we realized something was wrong. My husband went outside to look. This was the last time I saw him,” she told Jennifer Bose, emergency communications officer with international humanitarian agency CARE.

Despite the suffering, Almaz’s hardship was part of one of the most underreported crises in English, French and German news of 2018.

Why could this be? And what can we do about it?

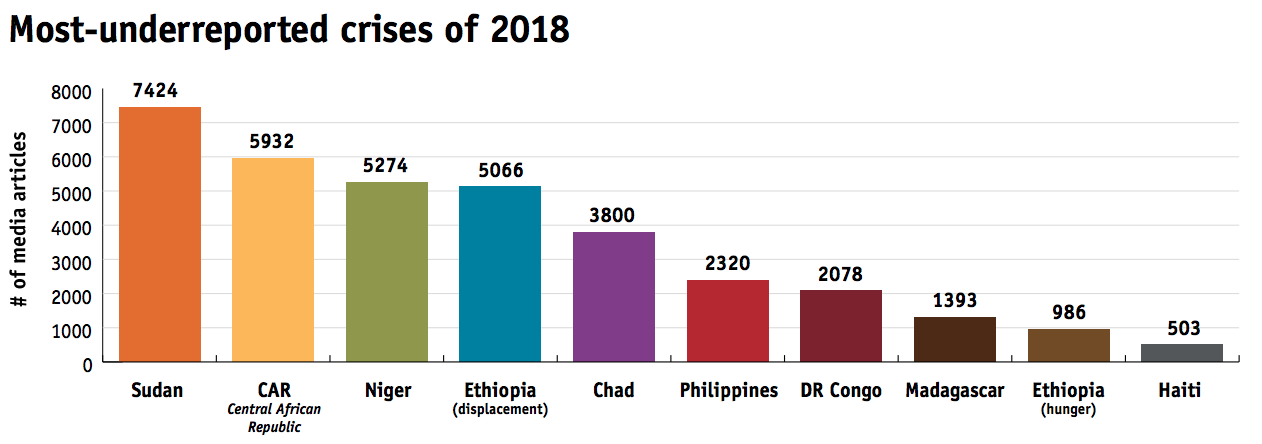

CARE worked with media intelligence firm Meltwater Group to determine which crises affecting more than a million people earned the least amount of news coverage.

The research, published Thursday in the report “Suffering in Silence”, found man-made crises and natural disasters in Ethiopia, Madagascar, Democratic Republic of Congo, Philippines, Chad, Niger, Central African Republic and Sudan garnered few headlines.

The most underreported was Haiti. Last year, drought contributed to more than 2.8 million people in need of assistance.

The reasons these situations received less coverage are as varied as the crises themselves. Shrinking news budgets force editors to make hard choices. Countries are difficult or dangerous to access. Certain regions carry more geopolitical weight than others.

Media coverage brings attention, which helps drive funding for emergency response efforts. For those living in makeshift shelters far from the spotlight, limited funding means aid dollars do not meet the need. This often leaves women and girls at greater risk as money is channeled towards basics like food or water, while vital reproductive health services or support to protect women from violence are shortchanged.

Sustained coverage also sparks important discussions about why this suffering exists in the first place. Climate change and prolonged conflict are leading factors in many of the crises listed in the CARE report.

Media access, visa issues and attacks on journalists continue to be some of the biggest obstacles for crisis reporting. According to Reporters Without Borders, the media is facing an unprecedented wave of hostility, with 80 journalists killed in connection with their work, a further 348 imprisoned and 60 held hostage in 2018.

Press freedom is essential to shine a light on issues that would otherwise be forgotten. UN member states, donors and aid agencies should insist on media access as a condition of political support and aid to affected countries. They must also speak out for the safety of journalists to do their work. This not only applies to international media, but is of vital importance to local journalists.

At the same time, in the age of reduced news budgets, we need to find new ways to allow journalists to see crises first hand, particularly places often beyond the typical news radar.

I attended a panel presentation in early 2018 where a Canadian journalist noted she would never accept support from an aid agency to travel as it would compromise her objectivity.

It’s a fair position and not uncommon. Like the humanitarian principles that underpin aid work, journalism ethics need to be held up to the highest standards as well. However, we do need to navigate how to respect the meaning behind conflict of interest guidelines and yet ensure important stories have an opportunity to be told.

There are a few options to consider. Donors can fund organizations that advocate for press freedom, train journalists or support foreign reporting. For example, since 2012, the R. James Travers Fellowship at Carleton University has financed journalists to launch foreign reporting projects. This scholarship has helped support in-depth coverage on several international issues.

The shift of news online does provide space for more diverse voices from Canada and abroad. Local journalists overseas can speak to Canadian networks via Skype. Canadian advocates from communities not typically represented can also highlight the suffering of friends and family back home.

But they do need more room to speak.

Given the number of humanitarian issues currently unfolding, it’s clear there is no easy fix to help people in distant lands.

While the conversation on the need to expand foreign coverage must continue, it should not be used to absolve governments from overlooking communities in crisis.

These are difficult times for journalism, but with the rise of fake news fueling fear and xenophobia, honest reporting is needed to show the human impact of politics, war and climate change on real people trying to move forward with their lives. They must not be allowed to suffer in silence.

Communication specialist for CARE Canada