Not gold, but close

This series was funded by readers like you through donations to the J-Source Patreon and FutureFunder at Carleton University.

In the summer of 2018, Angela Long embarked on a 22,000-kilometre journey, traversing eight provinces and a territory – from Dawson City, Yukon, to Cape Breton, N.S. – to learn from residents, reporters and experts about journalism’s importance in rural markets. In this series, she tells the stories of local news survivors and the roles they play in bolstering their communities.

“The toe has to touch your lips,” the bartender says.

She fiddles with her black velvet choker, turning to top off a pint. The lineup to drink a Sourtoe Cocktail, a shot of 40 proof liquor and a pickled toe, begins to form. “You’d better line up now or you’ll be waiting an hour,” she says.

“Is it a real toe?” a patron asks.

“Of course,” she laughs. “This is the North.”

She lines up shot glasses, filling them with Yukon Jack whisky.

Later, on the balcony of the Bunkhouse Hotel, the words of the bi-weekly Klondike Sun are still visible at 1 o’clock in the morning – the June sun has barely set in this town, just south of the Arctic Circle.

“AYC and the Gold Show made for busy weekends,” reads the headline. A photo of a prehistoric lion skeleton fills the page. By page five, drunken patrons begin to stagger out of the Sourdough Saloon and into the Land of the Midnight Sun. They look around, puzzled, it seems, by the light, unsure of whether to celebrate, or hide.

But there’s no hiding here.

Dawson City, Yukon. Population 2,323. Closer to Siberia than Toronto. Holland America buses cruise through the town’s unpaved streets. Motorcyclists wearing Harley Davidson leathers roar past the El Dorado Hotel. Convoys of RVers bob across the George Black Ferry, heading to the Top of the World highway, to Alaska, where towns with names like Chicken await. Dawson, heart of one of the biggest gold rushes in history, and the traditional lands of a Hän-speaking group of people, now part of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, displaced by hordes of the 1898 “stampeders,” has become the stuff of reality TV shows and National Film Board documentaries. Artists and writers apply to coveted residencies, hoping to stroll along the town’s wooden boardwalks, eat a bison burger, ogle at the northern lights. The Klondike Outreach Job Board lists dozens of employment opportunities: baristas, childcare providers, card dealers, lifeguards, soil samplers, room attendants. The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, a self-governing First Nation who comprise more than 18 per cent of the town’s population, prepare to celebrate 20 years of sovereignty.

And all of this is documented by Dawson’s non-profit media: a twice-a-month newspaper, a community radio station, a Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in newsletter. Here, at the confluence of the Klondike and Yukon rivers where two cultures once collided, a model based on a spirit of community collaboration and volunteerism ensures local media outlets keep the stories flowing.

“It’s not gold but it’s close,” reads the Klondike Sun sign on the blue clapboard building the newspaper shares with the Royal Canadian Legion. Behind a partition separating a studded faux-leather bar from the paper’s headquarters, a lone woman, Crystal Everitt, sits at a computer.

“You’re not from the Amazing Race, are you?” she asks, explaining how someone from the reality show on CTV had recently barged in with cameras rolling.

Due to spotty cellphone reception for several days – a common occurrence in rural municipalities such as Dawson – attempts to meet with editor and “head writer” Dan Davidson have been fruitless. But with Everitt’s help, Davidson is soon on the line. “Meet me at the Red Mammoth at 1,” he says and hangs up.

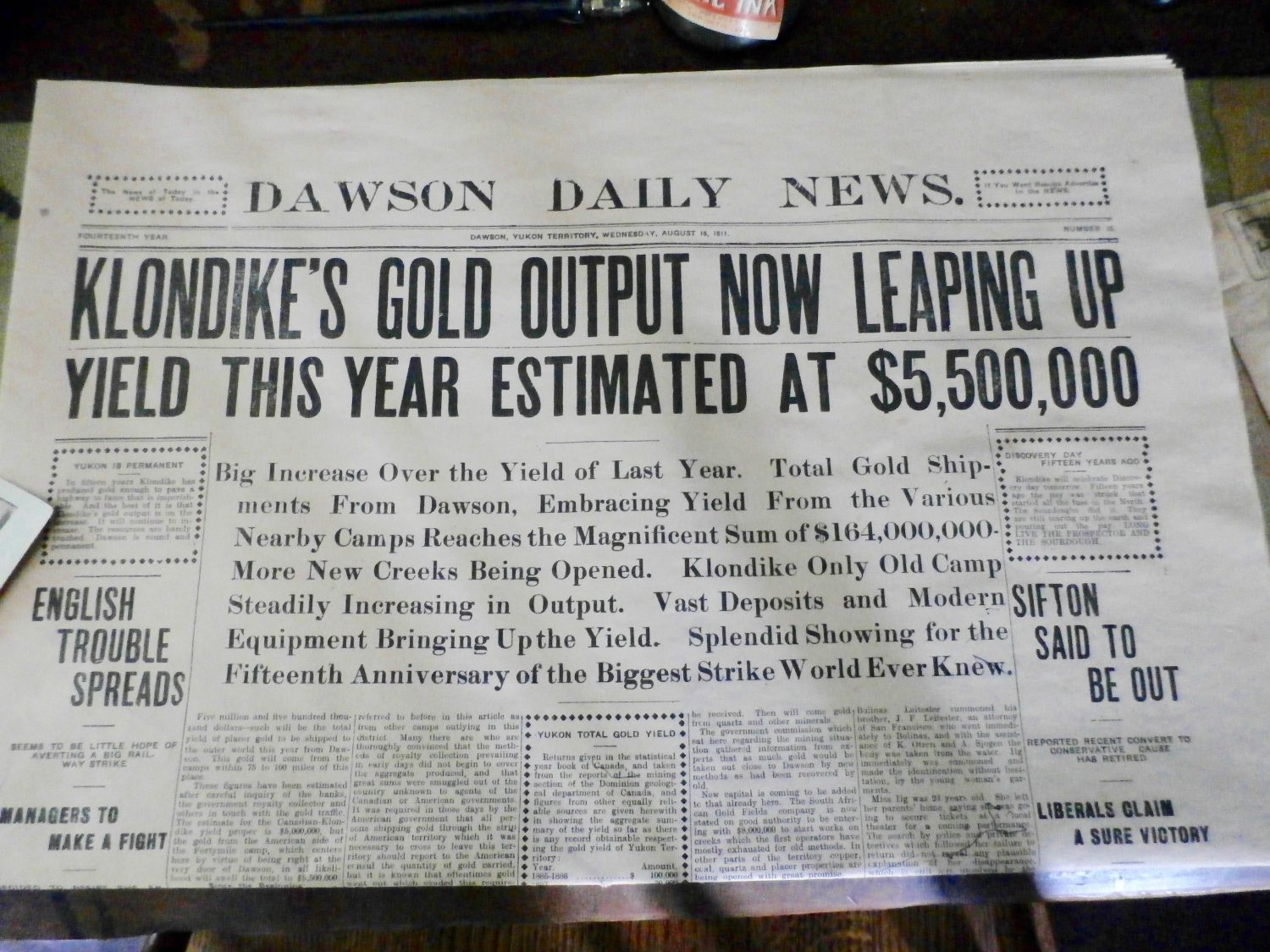

The media industry’s traditional model of doing business, relying mostly on advertising and print subscribers, has been disrupted to such an extent that the federal government recently announced a $595-million incentive package to support ailing Canadian news outlets. But in Dawson City, a place that has seen its early 1900s population decrease by tens of thousands; the purveyors of the fine silks, oysters and opera glasses of the “Paris of the North” close up shop; and at least seven daily newspapers go out of business (according to the government of Yukon Archives), change is nothing new.

The Klondike Sun’s current non-profit venture, however, poses its own challenges.

Davidson sips a cappuccino as the screen door of the Red Mammoth Bistro squeaks open, over and over, and slams closed. If other papers are forced to switch to a model reliant, for the most part, on volunteerism, he says, “We have a problem.” Especially, Davidson says, with people like United States President Donald Trump and Ontario Premier Doug Ford on the loose, media need all the resources they can get.

Everitt, the paper’s office and production manager, is the only paid employee. Everything else, from proofreading to distribution to photography, is volunteer work. Davidson, who retired from three decades of teaching in 2008, is able to do what he does partially because he freelances for publications such as the Whitehorse Star, based in the territory’s capital 532 kilometres away. He worries this kind of arrangement isn’t sustainable.

Nevertheless, Davidson believes in the power of local news no matter how small the population or how big the challenge. He began his community newspaper career as a science fiction book reviewer for a now defunct Halifax paper, the Fourth Estate, going on to work for the Faro Raven using an IBM Selectric typewriter when he and his wife moved to Faro, Yukon, (population 413) in 1979. When he moved to Dawson six years later and saw the local paper was “a bunch of ladies called The Nutty Club who got together to produce a newsletter,” or, as he calls it “a gossip paper,” Davidson saw an opportunity.

“If Faro was big enough for a paper, so was Dawson,” he decided. So, in the spring of 1989, a group of nearly a dozen like-minded citizens got together at the library to form the Literary Society of the Klondike, a registered non-profit society, and the Klondike Sun was born. Currently the society consists of a president, vice-president, treasurer, secretary and a four-member board of directors.

In 2009, the Whitehorse-based Yukon News reported on the Klondike Sun’s 20-year anniversary, marveling at its survival. “Publishing a newspaper in Whitehorse certainly has its challenges, but to publish for 20 years in a small community like Dawson City is another order of magnitude more difficult,” said former Yukon News publisher Steve Robertson. On three separate occasions, Dawson entrepreneurs had tried to start a for-profit competitor, and three times the Sun had “buried all of them.” Davidson was quoted by the Yukon News as saying, “The paper has never been about making money, just about making enough to get by, which confuses a lot of people who enjoy playing with business plans.”

Nearly 10 years later, with a print run of 600 and, as of January 2019, 1,009 Facebook followers, not much has changed. But Davidson doesn’t take anything for granted. “I don’t know what happens after I stop,” he says. “When I’m not doing it anymore it will be because I’m not able to do it anymore, and, I don’t want to sound like I’m blowing my own horn, but there isn’t anyone else putting as much into this as I do.”

Davidson takes a bite of his apple tart.

“I think I’m doing a public service, really,” he says. And he knows that when push comes to shove, the community values the Sun. Several years ago, when he thought the paper was about to go under, he created a GoFundMe account to ask for $5,000. The community donated $7,500.

Davidson says the “shock” of almost losing their paper caused a “revival in community interest.”

The paper sells about 450 copies twice a month at a newsstand price of $1.50. With less than 200 subscribers in Canada at $44 annually, 40 e-subscribers (at $29), plus readers who hail from Alaska (at $75) and the United Kingdom, and Belgium (at $125), the Sun survives almost exclusively on advertising and sales, says Davidson, to ensure Everitt gets paid for a 30-hour work week and that the paper’s operating costs are covered. The price of an ad ranges from $10 to $650 and government bodies – municipal, territorial and Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in – regularly buy up quarter to a half page of print ad space.

For now, Davidson’s biggest challenge is trying to cover everything happening in this subarctic town: the Commissioner’s Tea, the Commissioner’s Ball, the Print and Publishing Festival, the farewell dinner for the departing RCMP detachment officer. But it’s not all fluff. “Well, there’s the murder, which we don’t know much about yet,” he says. And the suicide at Pan of Gold, a pizza joint just down the street. “We’re just waiting for an obituary,” he says. The Red Mammoth door squeaks open and slams closed. Davidson stands up – time to get back to work.

Other local media players are also tuned into the challenges of the non-profit model.

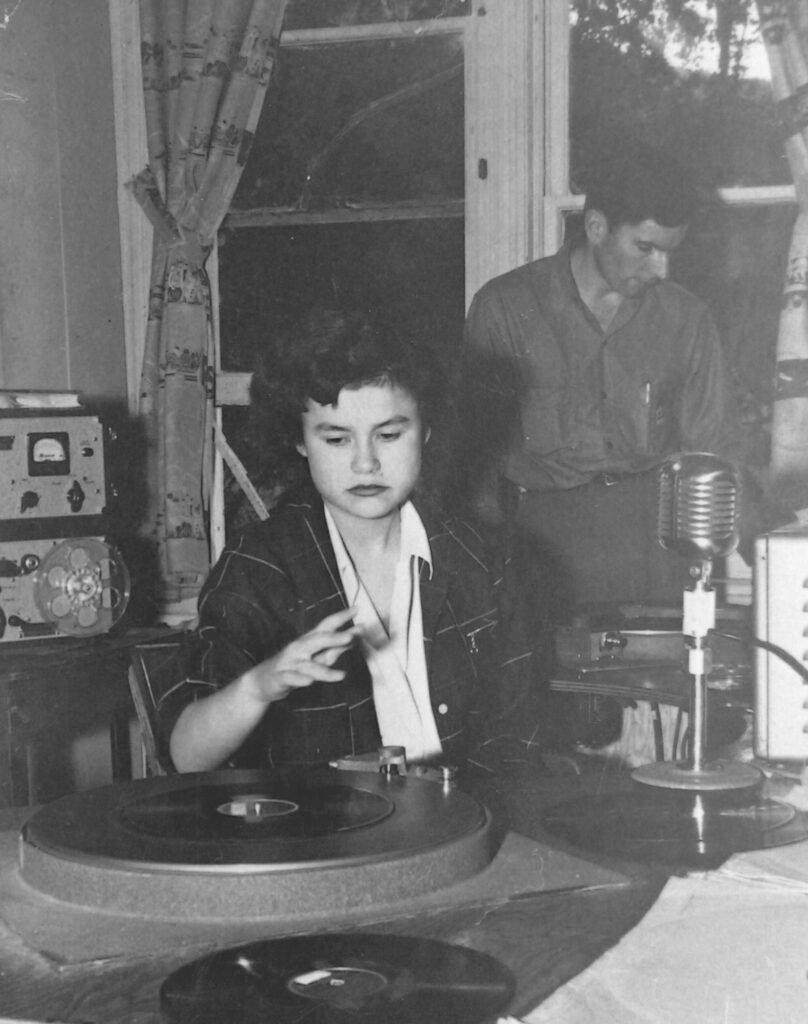

Peter Menzies, treasurer and founding member of Dawson City Community Radio Society, is aware of the looming question marks, but has faith in his community’s ability to make the most of its resources. The non-profit DCCRS has run the community radio station CFYT 106.9 FM –”The Spirit of Dawson”– since 1984.

Menzies, who, along with volunteering in nearly every community organization, works as a full-time applied skills instructor at Robert Service School. We sit in the school’s shop class, an airy space filled with equipment ranging from band saws to microphones. “I make radio compulsory in Grade 7,” he explains, opening cases filled with “remote” broadcasting equipment to cover the town’s long list of events and political forums.

From the incorporation of the City of Dawson in 1904, the town has been the site of three major stakeholders: industry, tourism and government, Menzies says. “They’re all big.”

Such a trio of what Menzies calls “capacity” creates an environment where community-based radio can exist: the revival of the mining industry (recently deemed a “21st century gold rush“), the more than 100,000 tourists (a record-breaker, according to the most recent Tourism Yukon report) and the territory’s per-capita allocation of federal support (one of the highest in Canada at $24,722). Dawson is home to a college, a visual arts school, a $30 million dollar hospital. All this, says Menzies, in the middle of nowhere: “Any small town of 2,000 in Canada would marvel at something like this.”

The radio station, Menzies says, is just another “piece of the puzzle.” It’s what you do with community capacity that counts.

In Dawson, a place where winter temperatures can plunge below 50 C and, for several months of the year, the sun sets a few hours after it rises, what people do is support each other. “There’s a spirit here,” Menzies says, “that even if you can’t stand each other we’ll figure out a way to collaborate, and there’s very, very few examples where that doesn’t exist.”

“I don’t want to overstate anything,” Menzies continues, fiddling with a piece of paper containing a Pavlova recipe. “What I’d rather talk about is that CFYT is there and it needs to be sustained. What I want people to understand is that it’s as much work to sustain something as it is to create it.”

The creation of the radio society 35 years ago occurred in a Dawson much different from a place the Globe and Mail recently called a “bucket list must-do.” Back then, the population hovered around 500, and “the whole north end was still outhouses,” Menzies recalls. The only surviving paper of the gold rush era, the Dawson Weekly News (formerly the Dawson Daily News), folded in 1954, and CFYT (Canadian Forces Yukon Territory), whose history began with the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals in a log cabin in 1923, was about to go bankrupt.

“There wasn’t much media up here,” says Menzies. “There weren’t even fax machines.”

Despite their own financial mishaps in the early 2000s, a string of relocations from a cabin to a rec centre to the top floor of an abandoned federal building, the DCCRS has survived, says Menzies, purely because of the collective will of his community. With an operating budget of approximately $20,000 a year, the station relies on a combination of fundraisers, territorial and federal grants, corporate sponsors, the sales of community advertising on local cable channel DCTV, and luck.

The DCCRS pays almost nothing in rent at its current Queen Street location, Menzies says. The organization’s existence depends on a fragile network of goodwill.

“We pass out the station’s security code to probably 50 people,” Menzies says. “If one person left the door open and a drunk went in and destroyed the place, if a brick went through the window, it would be over. But we don’t have these issues. I think that’s proof the radio station is respected.”

In tandem with the town’s growth, CFYT has evolved from four hours of music per week to four days of programming per week, including shows such as Pardon My French, Dude, How’s Your Stool?, and Angry & Queer in the North. If you drop by the station, you’ll see Menzies’ training in practice. Volunteer DJs have been taught to give back as much as they get from the experience of hosting their own show. One rainy afternoon, Allison (Poprocks) of Psychedelic Sundays, takes a few minutes between songs to chat. Before swiveling back to her console, Poprocks has issued invitations for a crocus viewing expedition, a walk up to The Dome and martinis at Bombay Peggy’s, a former brothel famous for its Dirty Jims and Blueballers.

Just around the corner from the station, the Dänojà Zho Cultural Centre sits on the banks of the Yukon River. The sound of a river making its way to the Bering Sea as it has for millenia fills the air. Homemade bannock fries on an outdoor grill while spruce-tip tea brews in a glass pot. Glenda Bolt –– Dänojà Zho curator and manager of 18 years who has been living on the traditional territory of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in for more than 30 years –– offers these treats to anyone who passes through the doors of the culture centre.

The centre, a “gateway to Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in heritage,” which opened in 1998, hosts one of CFYT’s most popular summer programs: Radio Zho Live by the Riverside.

“It takes a village to produce a radio talk show,” posts the culture centre on Facebook in August, 2018, marking the end of the 10th season on air.

During a phone interview, as the river begins to freeze and Bolt prepares for her winter holidays, she says the program was designed to “bring Hän language, stories, community events, special guests and live performance to CFYT airwaves, with a Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in focus.” Bolt cites examples of the local media and Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in working together in other ways, from coverage of an exhibition called “Where Are The Children? Healing the Legacy of the Residential Schools“ to partnering to produce a 30-minute radio documentary, “Trauma and Resilience,” part of a nation-wide project addressing reconciliation. Both Davidson and Menzies, says Bolt, “have been trying to address some of the Calls to Action before there was even such a thing. They do it, I think, from the heart. They know it’s the right thing.”

Historically, learning and working together with non-First Nations settlers has been a challenge in the Yukon. In 1973, the Council of Yukon First Nations (formerly the Council for the Yukon Indians) presented Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau with a “statement of grievances and principles for negotiating a land claim.” The document “Together Today for our Children Tomorrow” describes waves of contact – from fur traders to gold seekers to highway builders to pipeline workers, people that have “always come to the Yukon for money and left without really ever having experienced her quiet brown people or the majestic reaches of her land.” Among its many grievances, the nearly 50-year-old document expresses issues with the Yukon’s communications system: “We listen to Whitemen from the time we get up til we go to bed. Most of this is one-way communication.” The council calls for its people to learn media skills to tell their own stories, because “it has been so long since anyone listened.”

Bolt sees the CFYT program as an opportunity to “build cultural bridges,” finding ways for everyone to learn and work together. The hosts volunteer from the centre’s staff of Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in youth. One former host, Allison Anderson, now mentors students at Robert Service.

Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in citizens have their own newsletter, the Këntra Täy, or Moccasin Trail, which started over 20 years ago to keep citizens informed during the “heady days” leading up to the land claims final agreement ratification in 1998. Radio Zho, says Bolt, is a way to connect with the broader community.

“When you hear a Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in youth speaking Hän language,” Bolt says, “telling fish camp stories and giggling on the local radio, even giving the call letters for CFYT out in Hän language, it’s just so impressive, and it makes people vibrate with pride, both, I think, First-Nation citizens, but also non-First-Nation citizens – because everyone is in this together, right?”

This spirit of togetherness is on full display at the biennial Moosehide Gathering –– a four-day summer festival celebrating the cultural traditions of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in where “everyone is welcome.” CFYT broadcasts the event live. The Klondike Sun puts out a two-page spread.

While it’s these types of events that can attract coverage from bigger media outlets such as CBC North, Bolt stresses the importance of the local, day-to-day coverage.

“You know, having your photograph of you and your aunty, or your kids on a float, or doing something at the culture centre in the paper, adds a level of legitimacy and pride for community members” says Bolt. “We have to remember that although things are very good today, it was not always like this in Dawson.”

It’s the little things we should never underestimate, she says.

Editor’s note: This story was updated at 4:47 pm ET on Jan. 24, 2019 to reflect that Dan Davidson worked for, rather than helped start, the Faro Raven. We regret the error.

Angela Long is a freelance journalist based in Toronto currently working on a book about rural journalism in Canada.