Shrinking press galleries leave little time for journalists to dig deep

This story was funded by the J-Source Patreon campaign.

By Anda Zeng

A series of photos hangs on Jean LaRoche’s wall. The first shows the president of the Nova Scotia Legislative Press Gallery and CBC journalist amid a group of nine other smiling reporters outside Province House in the late 1990s. The other photo, taken this year, shows the same location, but the framing is closer, portrait rather than landscape, and LaRoche stands with only five others.

Since that most recent picture, the Chronicle Herald’s David Jackson went to work in the premier’s office. LaRoche said that of the remaining members, only he and one other reporter—Brian Flinn for AllNovaScotia.Com—cover the legislature on a dedicated daily basis, rather than coming in only for scrums or question period.

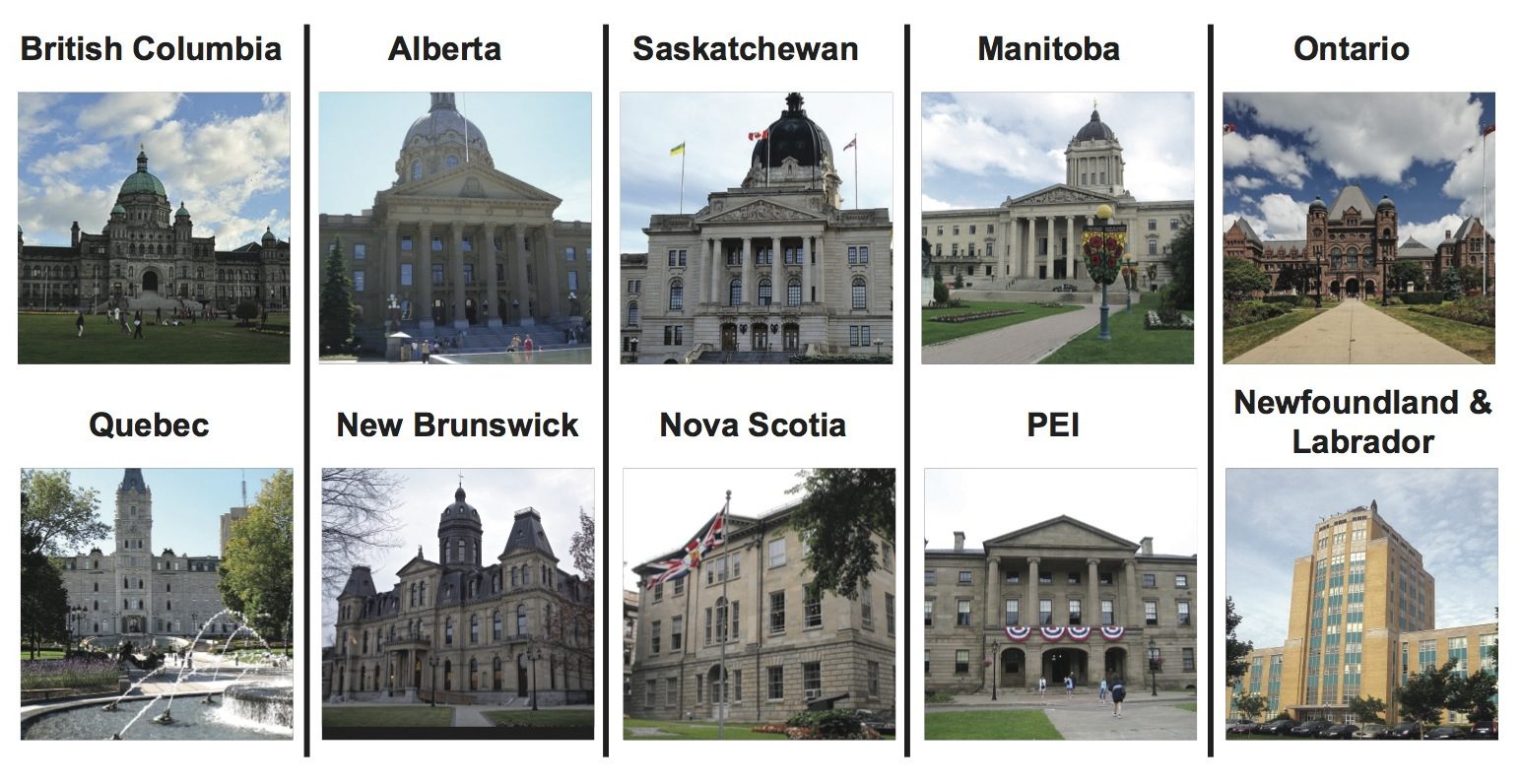

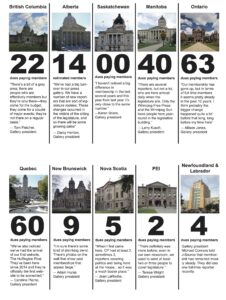

Nova Scotia is not the only press gallery to see ranks shrink. J-Source spoke with the presidents of provincial legislative press galleries across the country and found that other provincial press gallery presidents have noticed significant drops in their number over the last decade.

The Québec Parliamentary Press Gallery has had a 17-per-cent drop—72 members to 60 members—since 2006. Alberta and Prince Edward Island’s press galleries have seen their memberships whither; in PEI, only two dedicated, daily legislative reporters remain. In 2015, a lone citizen started a petition to have just one CBC reporter reinstated to the Saskatchewan legislature on a full-time basis.

Press gallery presidents who said their membership has remained mostly steady during their time in the legislature—Newfoundland and Labrador, British Columbia, New Brunswick and Manitoba— mentioned the effects of tightening resources weaving into their daily work. Reporters are under increasing pressure to cover more with less time, at the cost of the deep digging that holds politicians to account.

Photos on the walls of press gallery offices in Quebec also attest to a pattern of membership decline. The mosaics, as former gallery president Caroline Plante calls them, show almost a hundred members in 2003.

In the Ontario press gallery, the shrinking happened before president Allison Jones’ time. Local newspapers such as the London Free Press and local TV stations used to have correspondents at the legislature.

Diminishing numbers don’t mean provincial politics has lost news value. With the rise of a new NDP government after 44 years of Tory power in Alberta, press gallery president Darcy Henton sees a renewed interest in political affairs. “The big news events are covered by larger crowds than I have seen in recent years, so that’s a good thing,” the Calgary Herald political writer said.

But between the big events, not nearly enough reporters are at the ready with notebook or camera in hand, according to Henton. During this spring’s legislative session in Alberta, four events were scheduled for the same morning.

“I went on Twitter, and I questioned how they expected anybody to cover that event,” said Henton, referring to the fourth event that day, for the conservative Wildrose Party. “There weren’t enough members in the press gallery to cover that many events going on simultaneously.”

The Alberta Legislative Press Gallery had just undergone its latest shrinking via Postmedia newspapers combining newsrooms. Henton had begun to see his stories showing up in the Postmedia-owned Calgary and Edmonton Suns—even the National Post at times. The NDP government hired a number of press gallery reporters to be its media apparatus, and big turnovers in the press gallery meant a number of rookie reporters were still finding their way around.

The symptoms of converging financial instability and digital coverage ambition are evident in legislative press galleries, and not only in those who have been dealt a membership blow. B.C. press gallery president Tom Fletcher, who reports for Black Press, said that although the gallery roster has remained steady, television reporters do more off-site stories than before. Other press gallery presidents mentioned their CBC members going from two reporters to one who must file TV, radio and online reports.

Teresa Wright, acting president of the PEI press gallery, said that the Charlottetown Guardian used to send two or three people to cover legislature. One of those was a dedicated question period live-tweeter. Now, she’s the only one left, carrying the workload of three. After live-tweeting question period, she files an online story right away to produce original stories for print and web, which she will continue filing throughout the day.

Plante, a Montreal Gazette reporter who recently finished her mandate as president, finds she spends a lot of time running around trying to catch reactions. “Politicians will announce something in the morning, and so we’ll cover that. And then we’ll cover the reaction to that, and then the politician will react to the reaction, and so we’re always sort of running around because everybody’s reacting all the time,” she said.

General assignment and political reporters alike are simply not around as much to catch this constant cascade of response. In P.E.I., every news outlet sends a list of reporters who could potentially at some point be sent to cover legislature, but only Wright and CBC reporter Kerry Campbell have a daily presence. The threefold workload is strenuous, but Wright is dedicated to using her knowledge and experience to report intelligently on what happens on the floor.

“If you have someone coming in (who) doesn’t have that base of knowledge, they’re not going to recognize those times when something changes, and they’re not going to understand how to relay why that’s important and how that’s going to affect taxpayers,” she said.

Perhaps the harshest symptom of ongoing scarcity at legislative press galleries is the demand placed on journalists to adapt into multi-platform, ever-filing, hybrids with little time to pursue deeper stories. Part of a legislative reporter’s responsibility is to report what the government wants the public to know. “The other part of the job,” said Henton, “is to let the public know what the government doesn’t want them to know. And it gets harder to do the latter when you’re chasing to do the former.” Fewer people to turn over the rocks, he said.

The P.E.I. government passed legislation this spring that only received cursory coverage. Wright wants to delve further into those affected by the legislation, to hold the government accountable for how it uses its resources, especially as it pertains to the province’s most vulnerable. But her own lack of time and resources hinders her. “I’m a big believer in investigative journalism and long-form journalism,” she said. “That means taking your time with things. But sometimes, that’s just not possible.”

Small communities in particular can be subject to political reporting absent of subjects specifically relevant to them. Plante and LaRoche both mentioned that most regional papers in their provinces rely on the Canadian Press for legislative stories. LaRoche said it’s been a decade since he’s seen, for example, the Cape Breton Post send a stringer to legislative sittings; J-Source reached out to the Post for comment but received no response. Other publications used to send reporters down for particular issues, but he doesn’t see that anymore.

The life of every Nova Scotian is affected within the four walls of legislature, he said, and they should therefore watch their elected officials closely—and not only at budget time or during a 30-day campaign. “You judge them on their performance over the last four years and whether or not they really are advocating your aspirations and share your values.” To him, it’s vital to an informed electorate and effective democracy.

In an effort to allow for remote coverage, the office of Nova Scotia Premier Stephen McNeil recently started what they call Cabinet Out. Typically, a reporter would have to be physically present to scrum cabinet ministers. Now, every second week, the premier’s office sets up a microphone, and reporters outside Halifax can call in to ask their questions.

A few reporters have proven excellent provincial political journalism isn’t contingent on being in the building. Jones noted that the Ottawa Citizen’s David Reevely covers Queen’s Park remarkably well despite being based in Ottawa, not Toronto. He has broken multiple stories—Reevely was the first to report on the OPP investigation into the Liberal government’s sudden cancellation of a wind-farm development contract in 2011.

However, Reevely’s role at the paper is to cover how provincial politics affects Ottawa. His function is not that of a legislative reporter and neither is his focus. “Not that I’m fishing in a different pond, but I’m probably fishing in a different part of the pond,” he said. The dual advantages of his position are nearness to his readers and getting to complement what legislative journalists report—but he stressed that his role could never be a perfect substitute for full-time at Queen’s Park.

Whether Reevely and Nova Scotia’s Cabinet Out signal hope for legislative coverage remains to be seen. Though closing the distance, remote coverage may not build the same rapport and trust that Plante said is embedded into press gallery tradition. Distance does not allow for following daily events, questioning political leaders or tracking every comma in their speeches in quite the same way.

But Wright said there are always waves of change. “After a while, people reassess to figure out what’s important to their audience and to their community.”

Until this waves crests, she hopes resources will always be dedicated to ensuring politicians are challenged, that the media will continue to keep its watchful eye within the walls of legislative chambers.

With files from H.G. Watson.

Anda Zeng is a copy editor, paginator and freelance writer in Toronto. Her writing has appeared in Torontoist, Spacing and the Ryerson Review of Journalism.