U news you can use

Garett Williams became a reporter in 2008, writing for the Daily Miner and Newsin Kenora, Ontario. In a typical week he bounced between community activities: a pancake banquet in the morning, a Scouts badge ceremony at lunch, a youth hockey tournament before the day’s deadline. But these topics didn’t interest him. He wanted to write about social issues, government and laws — serious issues that impact people.

Williams spent five years at the Miner. In that time he watched it sold not once but twice, first to Sun Media and then to Post Media. Staff were let go, the already small paper got even smaller and he saw his “opportunities to expand disappear.”

Williams left the Miner in 2013 and enrolled at the University of Manitoba in Labour Studies. He signed up to write for the school’s paper, the Manitoban.

By the end of his first month he’d been to the provincial legislature, spoken to professors and board members about divestment and accessibility at the school, and covered local research into how gender is used in food marketing. At the Manitoban he found “a thriving environment for aspiring journalists” — a place to grow.

Flip through any campus publication and you’ll find a variety of content: photographs, news, opinions, literary submissions, cartoons, political coverage and more. The great majority of the publications are independent, financed through the gathering of a levy. That means a few dollars of each student’s tuition is allotted for the running of the school paper. For example, every student at the University of British Columbia pays $6.75 per year to their paper, the Ubyssey. With 55,000 students enrolled in 2017, that’s almost $377,000 a year.

These papers differ from most daily and weekly newspapers in Canada, the vast majority of which are part a large chain. In 2014 News Media Canada, an association representing publications across the country, released a comprehensive list of Canadian newspapers and their owners. Of the 90 daily papers printed across the country, six were independents. Of 1,000 community weeklies, almost 600 are owned by one of Canada’s ten major media corporations. Of the 114 campus publications, 102 are independent.

The size, format and frequency of university publications varies from school to school. At the Manitoban Williams coordinates 17 paid students and prints 8,000 copies per week for a student population of 30,000. The average campus publication shows similar numbers, employing between 10 and 20 students and printing enough copies for at least one-quarter of their populations. The 2016 census revealed the university population in Canada to be 1.3 million. That’s more than most of Canada’s major cities.

Campus papers bring campus – and sometimes city and national – news to those 1.3 million people. As Cameron Raynor puts it, “the CBC isn’t going to come cover your students’ union meeting — it’s the other students who are going to tell the stories.” Raynor is president of the Canadian University Press, a members network that connects post-secondary publications to conferences, workshops, legal services, an online wire service and each other. He believes these papers are giving students access to what “might be some of the best local news in the country.”

Circulation numbers suggest the students are reading it. Consider the Queen’s Journal in Kingston, Ontario. Queen’s University has 24,000 students, and twice a week the Journal prints 6,000 copies. That means their circulation is one-quarter of their population. The daily paper in the city is the Kingston Whig-Standard. The Whig prints 17,000 copies for a city population of 120,000, making their circulation one-seventh of the population. Of course, Whig subscriptions are paid.

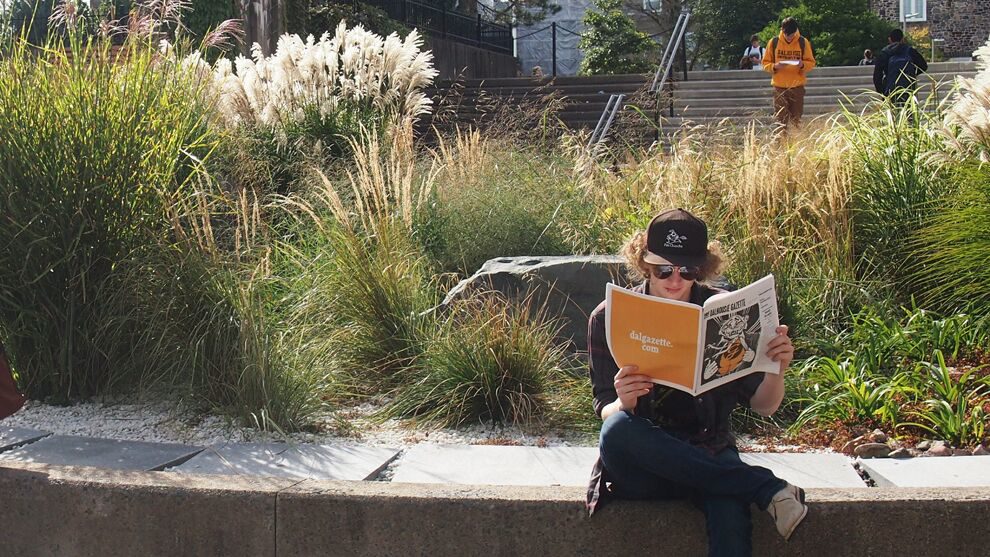

Dalhousie Gazette, have full office spaces where they can independently create their publications. Photo courtesy of AVIVA JACOB.

Is this really journalism?

Universities are complicated communities like any other. Those student union meetings Raynor was talking about are filled with discussions and votes, including the spending of hundreds of thousands of dollars per year.

Raynor used to edit his campus paper at the University of Alberta’s satellite Augustana campus. The paper, the Dagligtale, wasn’t independent from its student union. The executive members of the union were also the paper’s publishers.

Eventually there was a disagreement, and Raynor’s contract was terminated. He and staff members who followed him out the door,started an independent paper, the Augustana Medium. The paper is now in its second year. “Ideally,” said Raynor, “we exist to push (the Dagligtale) to do better, and to show our students what’s actually going on.”

Jack Hauen, editor-in-chief of the Ubyssey, believes truth is at the heart of his job. Last year Hauen and his team printed a document they obtained through a leak. It was the official admissions rubric, used to grade entrance essays to the school’s undergraduate programs.

Hauen said they printed it to lessen the divide between students from low-income and high-income families, and it took the Ubyssey four years to gather the information for the story. Hauen said the paper stuck with it because its staff are students — just like their readers. “Nobody can cover this stuff better than we can.”

Jason Herring, editor of the Gauntlet at the University of Calgary, feels the same way. His team has a direct line to the controversies on campus. He says it’s a very political environment. Just a few weeks into the fall term, students at the school came to class to find a confederate flag painted on a rock in a busy area. Over the course of the morning the rock was repainted several times. Students covered the flag with statements: “black lives matter,” “vote,” “heritage not hate”. Before long those statements were covered by conflicting ones: “Robert E. Lee did nothing wrong” and “Trump” surrounded by a heart.

“We can see the rock from our offices so we were right on it,” said Herring. He published a story about the incident on the Gauntlet’s website later that day. Just a few hours after the story went up, the CBC published one of its own. Reading through both stories, there’s one major difference: the Gauntlet had comment from the students responsible, and the CBC didn’t.

Editors of other campus papers have had similar experiences. Jacob Lorinc of the Varsity at the University of Toronto got first access to a professor at “the forefront of what became a national conversation” on the use of gendered pronouns in the classroom. Kaila Jefferd-Moore of theDalhousie Gazette was able to publish footage of arrests being made at a homecoming party because one of her writers happened to be at the party.

Garett Williams thinks he and his fellow student journalists have their “fingers on the pulse” of their communities. He wants to eventually go back to full-time reporting. His executive staff want to be journalists too; so do Hauen, Herring, Raynor, Lorinc and Jefferd-Moore. Williams doesn’t think they’re all that far off; their time at the papers has provided a decent footing as they near graduation.

“Student journalists deserve some respect for what they do,” said Williams. “I may not be a professional reporter anymore but (at the Manitoban) I’m still doing the job.”

This story originally appeared in the University of King’s College Signal, and is republished here with the author’s permission.

viva Jacob (aka Avi) is in the final year of her journalism degree at the University of King's College. She has focused on advanced research and investigative journalism with a minor specialization in law, justice and society. She plans to continue her studies while freelancing in the coming years. Her spare time is usually spent reading true crime novels or re-watching old TV shows. She can be reached at aviva.h.jacob@gmail.com or through her website www.avivajacob.ca