What happened when a B.C. student newspaper went toe-to-toe with access to information laws

UBC student newspaper the Ubyssey fought for admission rubrics for four years before the documents were leaked to them.

This story was funded by the J-Source Patreon campaign

By Mike Lakusiak

Four years and two legal decisions in their favour later, UBC’s student newspaper the Ubyssey abruptly concluded a battle for access to an admissions rubric this semester. An anonymous source unceremoniously handed the paper the materials they had been fighting for.

In the midst of UBC appealing a British Columbia Supreme Court decision the Ubyssey’s’s favour this February, Jack Hauen, the paper’s outgoing coordinating editor, received some startling information. “Someone who had seen our editorial saying UBC was appealing this again approached us,” he said.

“They said, ‘I saw your editorial, I have this, do you want it?’”

“There was definitely a sense that if we didn’t get this leaked, UBC would have fought it as long as they could and just tried to outspend us.”

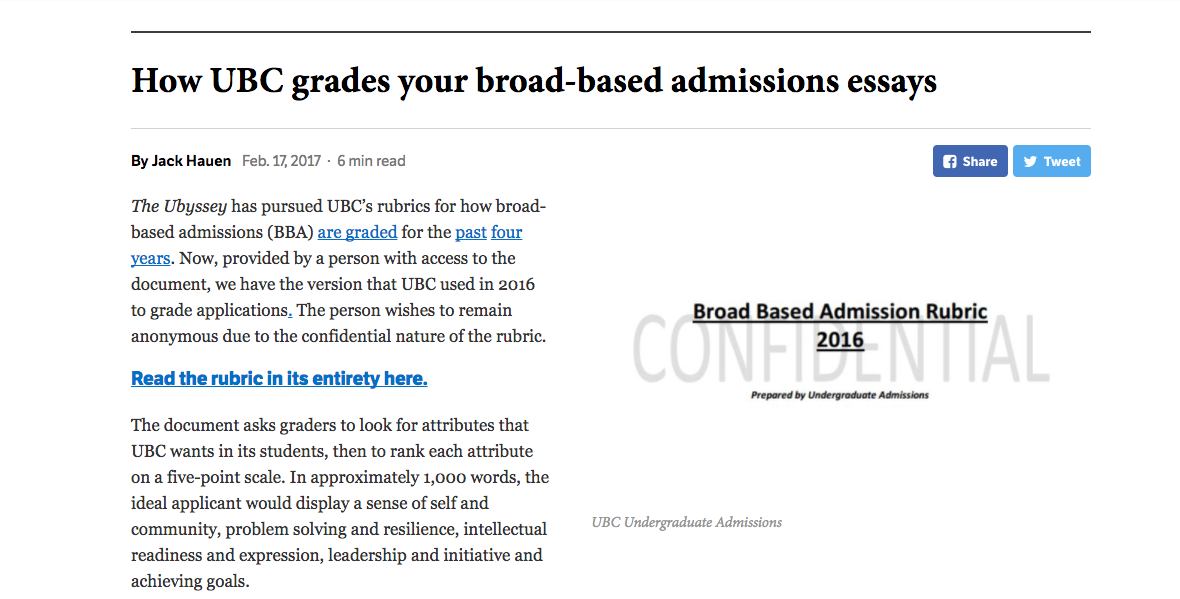

The rubric, a 2016 document marked “confidential,” was published by the paper in late February. It didn’t contain any explosive revelations (apart perhaps from the fact that spelling and grammar do not factor into the evaluation of students’ applications), but the question remains of why the university fought so hard for four years and several rulings to keep it confidential.

In this case the Ubyssey’s journalists ran into familiar, if particularly steep, hurdles to those faced by journalists in B.C. and across the country in their attempts to access public records.

Advocates for changes to provincial and federal access to information laws point to a culture of delay, lawyering and understaffing that, if not intended directly to discourage requests for public information like the Ubyssey’s, surely doesn’t help.

The rubric

The fight for access to the rubric began with former coordinating editor Geoff Lister in 2013, when Lister requested details of the then-new broad-based admissions model — a type of evaluation that not only considers a student’s high school grades but also their responses to a series of essay questions that consider their problem-solving skills and learning from situations outside the classroom.

Hauen said the university’s immediate resistance to release what the Ubyssey viewed as a basic public document sparked the protracted legal battle. “You wonder what’s in this thing,” he said, explaining the request’s journey through rulings in the paper’s favour by the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner (OIPC) and the Supreme Court of British Columbia.

“It’s partially our duty as a student paper to go after this and make UBC transparent but they’re legally obligated to give it to us.”

“It speaks a lot to UBC’s trouble with transparency,” he said. “It’s also just a fun story. It’s the scrappy underdog against the giant university. We felt justified the whole way through.We felt confident we weren’t doing it just to spite UBC — we actually had the law and morality on our side.”

In a statement issued after the leak and publishing of the rubric, the university’s director of undergraduate admissions, Andrew Arida, continued to justify the university’s dogged resistance on the matter.

“UBC has a legal right to appeal a January 2017 B.C. Supreme Court ruling requiring it to release its broad-based admissions scoring guides. Releasing these scoring guides would allow prospective students to tailor their answers to meet UBC’s requirements, seriously harming UBC’s ability to properly evaluate applicants.” He added that the broad-based admissions mechanism is widely used and factors in prospective students’ experiences along with their grades.

Hauen said this rationale doesn’t cut it. For the Ubyssey it was about giving prospective students a better chance, especially if they didn’t have a guidance counselor to support them. “If your professor gives you a rubric for an essay, you don’t say, ‘What an idiot, he just gave me the answers’,” he laughed.

The state of FOI

Tom Henheffer of Canadian Journalists for Free Expression in Toronto didn’t mince words when asked about the state of access to information law and practice in B.C. “It’s a fucking dumpster fire across the country. I’d say your dumpster is slightly more on fire.”

While he credited the provincial legislation that gives the information and privacy commissioner order-making power — making decisions of the commissioner on par with court decisions — he lamented how things actually play out.

“Order-making power is great but if there are loopholes around it it makes it extremely difficult for information to come out and that’s the problem,” Henheffer said. “It’s incredibly crass and cynical to say, but they’re more than willing to abuse convention and what the constitution is supposed to represent in order to prevent any potentially embarrassing information from getting out.”

In B.C., the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act stipulates that when an FOI request is made, a public body has 30 business days to respond, although it may take extensions in certain circumstances.

Complaints about how public bodies respond to requests are escalated to the provincial Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner. According to a spokesperson for the OIPC, the office received 1,096 complaints about access to information and requests for review last year. Only two cases were escalated for judicial review to the B.C. Supreme Court —one was the Ubyssey’s request for the admissions rubric.

Henheffer said understaffing of offices in charge of responding to requests for public information is a consistent problem across lots of institutions. “There’s nothing compelling them to (hire more staff),” he said. “It’s BS whenever an institution says they’re overrun with requests. That’s because they chronically underfund their departments.”

The Office

The Ubyssey’s Hauen said his paper’s interactions with the university’s FOI office are overwhelmingly positive, but he’s realistic and noted that he’s spoken to journalists at other campus publications who have it much worse.

“UBC’s FOI office is incredibly overloaded all the time and I feel very bad for the people that work there because they are not the ones who want to put up roadblocks to us accessing information. All signs point to them doing their best.”

“UBC never meets the 30-day deadline. They always extend it another 30 days and even then they’re usually late after that.”

The Ubyssey wrote about the office’s two overloaded staff members in 2015, as the resignation of UBC’s president six months into the job prompted a flurry of access to information requests. At the time, the university’s legal counsel in charge of access to information Paul Hancock said the average file completion time was 40 days. Hancock was not available for comment before deadline.

The office received well over 300 requests for information in 2016. As of 2017, there is a Freedom of Information Specialist and two Freedom of Information Assistants listed on the Office of the University Counsel site.

Looking for change

Vincent Gogolek, executive director of the BC Freedom of Information and Privacy Association, is pushing for more teeth to B.C.’s access to information laws.

He said that while there aren’t specific requirements around staffing for the offices who handle requests, being consistently outside of the 30-day parameter is not okay.

“You have a legal obligation to respond,” he said. “In B.C. and federally, there’s a duty to assist requesters. They should not be under-manning their FOI shops.”

He’s pushing for actual penalties for noncompliance. But he acknowledged it’s not realistic to hire staff immediately to respond to the volume of requests that come in during a big news event or scandal.

“If the same kind of patterns can be seen in a public body, they should be smacked down, in my mind anyway. There’s a lack of any kind of sanction and people generally want to see that.”

Overall Gogolek remains positive that with some teeth to the laws and the continued persistence of journalists to fight for access to public information, it’s not all bleak.

“We win some too,” he said. “To the extent that they drag their heels and try to delay, the main thing is to not give up, because that’s what they want.”

“It can be frustrating but as a journalist you know FOIs are where you get some of the best stuff from.”

Disclosure: Mike Lakusiak is a contract employee at UBC’s Graduate School of Journalism.

Mike Lakusiak is a Vancouver-based journalist and video producer. A graduate of the UBC Graduate School of Journalism, his work has appeared on CBC Radio and VICE News. He was a 2016 Carnegie-Knight News21 Fellow.