In 2014, a grisly video surfaced showing workers physically abusing cows at Canada’s largest dairy farm in Chilliwack, B.C. Captured via hidden camera, the footage was taken by an undercover investigator from animal advocacy organization Mercy for Animals Canada.

After being picked up by media and broadcast on live television, the exposé — which revealed workers kicking and punching cows in the face and body, whipping them with canes and chains, ripping out their hair and dragging one by the neck using a tractor — eventually led to guilty pleas from seven workers on 20 counts of animal cruelty, jail sentences for six of them and a $350,000 fine against Chilliwack Cattle Sales. Those convictions marked the first time factory farm workers had been sentenced to jail for animal abuse following an undercover investigation by an animal protection group.

Anna Pippus, who was director of legal advocacy at Mercy for Animals Canada at the time, told CBC News that their investigator applied to work at a number of facilities and did not target the Chilliwack farm; it was just the first to hire him. In a press conference, Pippus also claimed their investigator tried to bring concerns to company owners who failed to take corrective action. “That leads us to believe that cruelty to animals runs rampant on factory farms,” she said.

Now, critics say the possibility of agricultural investigations like the Chilliwack dairy farm exposé are being threatened by legislation that will prevent whistleblowers and investigative journalists from exposing illegal or unethical farming practices.

Dubbed an ‘ag gag’ law, Ontario’s recently-passed Bill 156, or the Security from Trespass and Protecting Food Safety Act, is framed as intending to protect farmers, animals, food supply and others from intrusion and risks created by trespassers, such as “exposing farm animals to disease and stress.” Bill 156 follows Alberta’s Bill 27 passed last November, the first legislation of its type introduced in Canada.

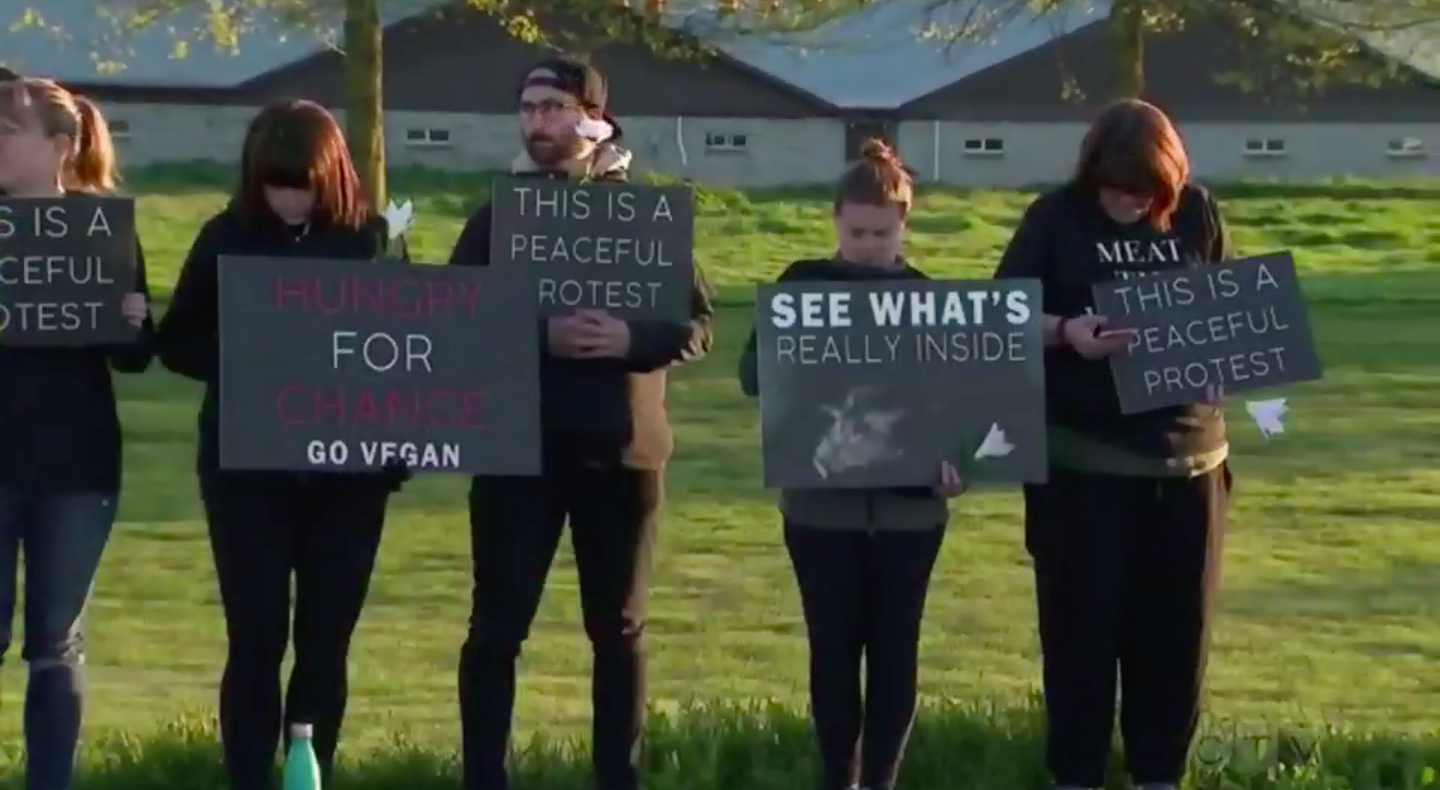

However, Ontario journalists and animal rights activists have raised the alarm over Bill 156 and its implications for the public’s right to know.

On June 10, the Canadian Association of Journalists released a statement condemning Bill 156 and highlighting a number of concerning consequences. According to the statement, the new law does not allow protections for whistleblowers, would criminalize undercover investigators entering animal protection zones or interacting with drivers “under false pretences” and expose journalists to lawsuits for doing their jobs.

The statement also notes that similar legislation in the United States has been struck down and deemed to violate the U.S. constitution’s First Amendment provisions of free speech, principles also protected under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Over 40 legal experts signed a letter to the government advising Bill 156 to be unconstitutional, and a petition urging members of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario to oppose the bill amassed over 75,000 signatures.

“These exposés have often resulted in animal cruelty charges and major media features on programs like W5, CTV National News and CBC Marketplace,” said Camille Labchuk, animal rights lawyer and executive director of Animal Justice, a national animal law non-profit.

According to the CBC’s Journalistic Standards and Practices, “When the investigation bears on illegal or antisocial behaviour or abuse of trust and the gathering of information of public interest, the journalist may need to infiltrate an organization to get first-hand information.”

“The bill makes it an offence to gain access to a facility under false pretenses. That would mean that an undercover investigative journalist or an employee whistleblower who doesn’t disclose their full intentions on a job application could be subject to fines up to $25,000,” said Labchuk.

“There’s a pretty long history of using these types of investigative techniques in journalism and they’re a completely legitimate thing to do. As people are increasingly concerned about where their food comes from, it would be my expectation that there would be more interest from journalistic outlets in doing this kind of work,” she said.

According to Colombe Nadeau-O’Shea, donor relations manager for Mercy for Animals (MFA), critical investigations like the Chilliwack exposé “just would not be possible” under the bill.

Furthermore, according to Nadeau-O’Shea, the bill hearing process was not as transparent as it should have been.

“They tried to push through in the middle of a pandemic,” Nadeau-O’Shea said of the legislative proceedings. “Normally, these hearings would be broadcast to the public. But because of what the government described as technical issues, much of the legislative debate happened behind closed doors.

“There are obviously a lot of issues with this bill, and I think they’re just trying to get it pushed through while they can.”

Carleton MPP Goldie Ghamari, who chairs the standing committee on general government which administered the hearing, did not respond to a request for comment.

President of the Ontario Federation of Agriculture Keith Currie said that there are still avenues whistleblowers can use to expose suspected legal or ethical problems on farms, such as the Provincial Animal Welfare Services (PAWS) Act, which came into force on Jan. 1. The legislation outlined an increase in provincial inspectors, higher fines of up to $1 million for corporations repeatedly found guilty of animal cruelty and new oversight for inspectors, as well as a complaint mechanism for inspector conduct.

Along with the PAWS Act, Ontario established a toll-free, 24/7 tip line to report concerns about animal abuse. Currie said whistleblowers can call this line if they suspect wrongdoing on farms, following which the complaint will be reviewed and, if warranted, a provincial inspector will conduct an independent investigation.

“Call the proper authorities who are trained to understand what to look for and how to deal with this,” said Currie. “If you’re being hired under false pretenses, what really is your goal? Is it trying to uncover something that’s going wrong, or do you have an ulterior motive?”

However, Nadeau-O’Shea said previous Mercy for Animals investigations have shown individuals tasked with oversight to be complicit in animal abuse. Footage from the group’s 2014 investigation into the Western Hog Exchange and abuse in the Canadian pork transportation system caught inspectors from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency either failing to act when animals were being abused in their presence, or actively facilitating the abuse.

In some instances, CFIA inspectors were seen handing electric prods to workers to use on pigs — a clear violation of Western Hog Exchange regulations, which says “prods are not allowed to be used in the barn to move hogs,” according to CTV News.

The undercover MFA investigator said, “it seemed as though [the CFIA inspectors] were there to be a presence, to give people assurance that animal welfare is being taken care of. But I didn’t see them doing anything to really enforce that.” At one point, as a truck comes in with a couple of dead pigs onboard, a CFIA inspector said: “If anybody has a camera, this’ll be on the internet.”

When the CFIA was asked for information on what inspectors found while hidden cameras were rolling, they said they did not issue a single violation or warning after conducting 84 “humane transportation verifications” between May and August 2014.

“We can’t rely on the current system, which is not built to protect animals or workers, it’s built to protect industry,” said Nadeau-O’Shea. “If we could, we wouldn’t have to do undercover exposés.”

MFA has conducted the majority of undercover agriculture investigations since 2012. While news outlets often publish footage obtained through animal rights organizations, Canadian journalists rarely go undercover on farms themselves, which Labchuk attributes not to lack of interest but underfunding of newsrooms and investigative journalism generally.

Jessica Scott-Reid is a freelance writer and advocate who mainly covers animal rights and welfare, and has been covering Bill 156 since it was proposed in early December 2019. Even though there’s a dearth of journalists covering agriculture full time, she said interest in the stories she covers has been steadily mounting.

“Five years ago, I used to have to fight for these pieces to get into the paper. Now they’re very interested in having them done,” said Scott-Reid. “I think there’s a concern about the credibility of animal rights organizations.”

On June 23, the Toronto Star published an investigation into Scotlynn Growers, a Norfolk County farming operation where 199 migrant workers have tested positive for COVID-19, and one has died. According to the Star report, Mexican migrant workers at Scotlynn tried repeatedly to raise what they described as “unsafe and sometimes hazardous” living conditions, like bedbugs, or being offered cash to return to Mexico without reporting an injury sustained on the job, one claimed. One worker who said he has experience on multiple Canadian farms told the Star that employers and authorities often “seemed slow to react to concerns about living and working conditions.”

But Currie maintains that Bill 156 is really just about protecting the safety of farmers, their employees and their families from trespassers. “What’s happened these last few years is a real escalation of invasion of private property … these activists come onto our farms, literally break into our buildings. They’re endangering our families, our children, our employees.”

If caught trespassing on a farm, offenders could be fined up to $25,000, compared to a maximum of $10,000 under the Trespass to Property Act.

“Fines within the trespass act are not very strong and quite often the police won’t bother investigating or charging,” said Currie. “It’s not likely to get a conviction … because the court costs are so high compared to the actual fine that would be laid.”

Nadeau-O’Shea told J-Source that MFA does not engage in trespassing, and that farm occupations are “an extremely rare phenomenon.”

“Mercy for Animals whistleblowers follow all health and safety rules and protocols during their time at the facility. They follow every other rule that any other worker is following,” she said. “If biosecurity is really as important as they’re claiming, why isn’t the government legislating standards? Why doesn’t this bill make it an offence to create a biosecurity risk instead of focusing narrowly on trespassing?”

Part of Bill 156 also makes it illegal to enter not just farming sites but anything deemed an Animal Protection Zone, including transport trucks and biosecurity areas around buildings. On June 23, longtime animal rights activist Regan Russell was struck and killed by a transport truck outside a slaughterhouse in Burlington. Russell was outside the processing plant holding a vigil — in which activists bear witness to animals and provide them with water before they’re killed. “She was out there that day in particular because we know with Bill 156, these vigils beside these trucks will soon be highly illegal,” said Scott-Reid.

Labchuk said she’s concerned the bill “has emboldened the meat industry to declare open season on animal advocates.”

An eerie TikTok video circulated shortly before Russell’s death shows a truck driver pretending to run over protesters, while the comments showed an abundance of support from other truckers. One comment read: “Vegan bowling.”

“The legislation also empowers and gives legal authority to farmers and truckers to arrest animal activists … the law essentially turns farmers into your police force,” said Labchuk. Scott-Reid echoed the sentiment, saying she believes Bill 156 “absolutely gives people in the industry some sense of power that they already had and shouldn’t have anymore of.”

“It doesn’t feel like a coincidence to us that Regan Russell’s death came just two days after this legislation passed,” Labchuk said.

Currie, however, said Bill 156 is intended to not only keep farmers and animals safe, but protesters too. “We were concerned as an organization that something like this could happen if we didn’t somehow get some better rules in place for the protection of everybody,” he said. “We also need to protect the animals because people are running up with bottles of liquid and we don’t know whether that’s water, or something that’s a foreign substance that’ll cause harm to that food.”

Anita Krajnc, founder of vegan advocacy group Toronto Pig Save, made headlines in 2015 after she was charged with mischief for giving water to pigs on their way to slaughter. A judge found her not guilty because she didn’t harm the animals or prevent them from being slaughtered, according to the Star.

“We as Canadians I think are pretty trusting of governments, we expect and desire that our governments are regulating industries in the public interest and protecting the vulnerable,” said Labchuk. “I think you see the same kind of shock when people learn about the situation in long-term care homes.”

Animal Justice is preparing to file a lawsuit challenging the “unconstitutional” aspects of the law, which will be filed once the provincial government outlines regulations to accompany the bill and the law comes into effect.