More than two years into the pandemic, news organizations in Canada are reimagining futures that entail navigating the ongoing public health crisis, an evolving economic landscape and a radically different relationship with the public that has made journalism a riskier occupation.

There is positive news: There has been an uptick in local online news startups. In some notable cases, digital-born publications are thriving thanks to audience and philanthropic support. The number of Canadians who pay for online news or access paid online news services is growing, albeit slowly. New mentorship programs are offering points of entry and support for historically underrepresented media workers. Many newsrooms are deepening their relationships with the people who listen to, watch and read their content. And as with other businesses, federal government subsidies kept many news outlets alive during lockdowns and other COVID-related restrictions.

But there have also been major challenges. Advertising revenue tanked during the pandemic and its future as a source of funding for news remains uncertain. Federal COVID-19 subsidies that pumped hundreds of millions of dollars into news organizations are no more. Some news outlets and jobs permanently disappeared. Toxicity in virtual spaces has increasingly morphed into hostility targeting media workers on the ground and news avoidance is on the rise.

“The pandemic had one basic effect on news media, which is that it sped up every trend. Some of (those trends) are good things, some are bad,” said Bob Cox, the recently retired publisher of the Winnipeg Free Press and former chair of News Media Canada, an industry lobby group for print and digital media.

In this report we draw upon information gathered from the COVID-19 Media Impact Map for Canada, interviews with industry players, and the latest research to provide an overview of the pandemic’s impact on news media since March 11, 2020, when the World Health Organization declared a worldwide pandemic. The review wasn’t all-encompassing as our data do not sufficiently capture the effects of COVID-19 on freelance media workers or multicultural and third-language media, but we did identify some major trends.

Love and hate in the time of COVID-19

The relationship between the public and news media started well in the early days of the pandemic. Many news organizations saw substantial audience growth and many, if they relied upon subscriptions for revenue, temporarily made paywalled COVID-related content available for free. In mid-2020, when Statistics Canada asked people which online sources they relied upon for COVID-19 information, 63 per cent of respondents cited online newspapers or news sites while 35 per cent used social media posts by news organizations.

Cox said the Winnipeg Free Press received a lot of love in those early days: “We actually got people sending us donations to make sure that we could keep publishing.”

Tai Huynh, editor-in-chief of The Local, a digital publication that has covered urban health and social issues in Toronto since 2019, said monthly pageviews quadrupled from about 25,000 pre-pandemic to more than 100,000 with the rollout of award-winning coverage documenting high infection rates and low COVID-19 vaccine availability in the Greater Toronto Area’s Peel Region.

“Had we set up The Local to cover arts in Toronto it would have been a different story,” Huynh said. “People were hungry for our content because it helped them make decisions.” About 60 per cent of The Local’s funding now comes from philanthropy, he said, and the 15 per cent from reader donations is growing quickly. Grants are the other main revenue source.

Huynh was not alone in observing that audience support over the past two-and-a-half years translated into a willingness to pay for content.

“We had a huge surge in new members right around the beginning of the pandemic,” said Emma Gilchrist, the editor-in-chief and co-founder of The Narwhal. The digital magazine, which covers environmental issues, had about 1,000 members in early 2020, she said. This spring it had 5,000.

“We were experiencing a lot of success in getting readers to convert into paying members, which was a little bit surprising even to us,” Gilchrist said.

Both The Local and The Narwhal, which do not have paywalls or sell advertising, received a boost during the pandemic because they were among the first eight non-profit news organizations to become registered journalism organizations. This Canada Revenue Agency designation allows them to issue tax receipts to individual donors and more easily secure funding from philanthropic foundations.

But as the pandemic dragged on, the news media’s honeymoon with the public didn’t last.

Early stumbles included the CBC’s decision to halt local supper-hour and late-night TV newscasts as of March 18, 2020. The announcement that local coverage would be replaced with a “core news offering” from the CBC News Network cable service sparked widespread outrage including from P.E.I. Premier Dennis King, who tweeted it was “vital” for Islanders to have access to the latest local information. A week after pulling the newscasts, the public broadcaster began gradually restoring local coverage.

Other self-inflicted wounds were more systemic. In “Spin Doctors: How Media and Politicians Misdiagnosed the COVID-19 Pandemic,” journalist and author Nora Loreto makes the case that media failed to challenge government narratives and engage critically with data about workplace outbreaks and long-term care deaths in the first year of the pandemic. Another early analysis argued news media historically failed to bring a critical lens to private-sector profit in long-term care.

There were also outside forces bearing down, including in some cases, reporters’ limited access to hospitals and government officials that prevented them from documenting eyewitness stories about the reality of COVID-19.

And as disinformation accelerated virtually and globally, media in Canada lacked the tools to fight back.

Trust in the Canadian news media fell to the lowest point in seven years in 2022, according to the latest Canadian survey data from the Reuters Institute’s 2022 Digital News Report. Only 42 per cent of Canadian respondents said they “trust news, most of the time,” down from 45 per cent in 2021 and 13 percentage points lower than in 2016.

On the ground, public antipathy toward journalists escalated beyond virtual threats to physical violence, a development that experts warned would come to pass. Online hate and harassment that was trending upward before the pandemic increased. So did alarming face-to-face verbal attacks, threats and in some cases physical violence associated with events such as the convoy protesters in Ottawa earlier this year and the targeting of media workers by People’s Party of Canada leader Maxime Bernier last fall.

Cox said the level of animosity directed at the Free Press during the Ottawa protests was “unprecedented.” He and his staff received personal threats and “we had people coming into the building, trying to serve (legal) papers on our editors, saying that they had broken the law” and committed high treason.

Preliminary data from the Canada Press Freedom Project, a new J-Source-led initiative that tracks press freedom violations, recorded at least 21 documented incidents of harassment and intimidation and at least seven assaults of media workers at convoy-related events alone. In the majority of cases, broadcast workers were targeted. Alberta broadcasters opted to remove all identifiers from their vehicles in the wake of ongoing threats.

Harassment and threats proliferate

A 2022 survey that examined the mental health of media workers found that 85 per cent of video journalists, 71 per cent of photographers, 67 per cent of hosts/presenters, 55 per cent of reporters and 53 per cent of camera operators reported “worsening online harassment.”

An Ipsos survey of online harassment published in November 2021 showed that more than one in 10 journalists who experienced online harassment reported receiving death threats.

The more frequent and severe levels of online harassment and direct threats targeting younger, racialized, women and LGBTQ2+ workers forced the industry to acknowledge a long-standing workplace safety risk that disproportionately affects these groups.

The hate directed at reporters, combined with exhaustion among newsroom leaders, has led to an exodus of talent to public relations and other fields, said Fiona Conway, immediate past president of RTDNA Canada, the association representing news managers and broadcast and digital journalists.

“The burnout (among managers) is terrible,” she said. Reporters, she added, are saying “‘I’m done. I don’t want to be harassed anymore.’”

“There’s a lot of institutional knowledge that’s being lost.”

The pandemic’s economic toll

The advertising revenue that historically funded newsroom operations has been in decline for years but the pandemic accelerated that trend as many businesses shut down for months at a time. Statistics Canada reported that advertising revenue for private television fell 17.4 per cent in 2020, compared to a year earlier. In the case of private radio, it dropped 23.5 per cent to the lowest level since 2003.

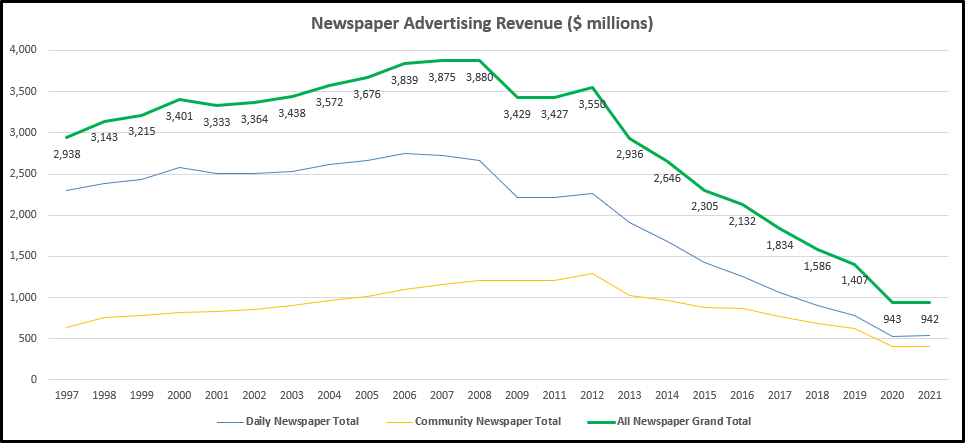

The latest data from News Media Canada also documents a precipitous decline in newspaper advertising revenue: It fell by about a third or $464 million in 2020 from a year earlier with no sign of recovery in 2021.

NOTE: Totals are for digital, print and flyer advertising revenue. SOURCE: News Media Canada December 2021

Overall ad spending in traditional media recovered only slightly last year and is expected to be flat in 2022, according to the latest MiQ and eMarketer Insider Intelligence report. Digital ads, meanwhile, will account for slightly more than 68 per cent of the total advertising market this year with the Google/Meta duopoly gobbling up about two-thirds of that spending.

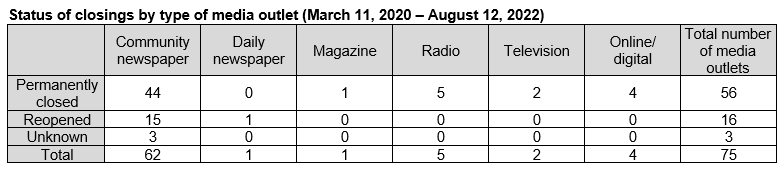

The revenue losses took their toll. The pandemic was cited as a factor in the permanent closing of 56 local, regional and national media outlets and the temporary shutdown of 16, according to data from the COVID-19 Media Impact Map for Canada, a joint initiative of J-Source, the Canadian Association of Journalists and the Local News Research Project at Toronto Metropolitan University.

NOTE: This chart only includes cases where the pandemic was explicitly mentioned as a cause for closing. Figures include local, regional and national media. SOURCE: COVID-19 Media Impact Map for Canada

The pandemic was also hard on alternative weeklies, which over the years have been important sources of community and cultural news. The fate of Now Magazine is a case in point: Media Central, which acquired the 40-year-old Toronto brand in 2019, moved early in the pandemic to curtail its print distribution, temporarily lay off seven staff and reduce hours for the rest of its workers. In March 2022, weeks before the company filed for bankruptcy, Now announced its print edition would move to monthly from weekly. The last print issue for the foreseeable future, which appeared earlier this month, was produced by a skeleton crew.

The blurring of the lines between print and online news operations, meanwhile, continued during the pandemic. In total, 59 magazines, daily newspapers and community newspapers (published less frequently than dailies) cancelled some or all print editions.

The majority of cancellations were temporary, but eight local newspapers (one daily and seven community newspapers) shifted fully to digital while 22 papers (16 dailies and six community papers) permanently cut back their print editions, according to data from Local News Map, which tracks changes to local media. These numbers are up slightly compared to the years immediately before the pandemic.

On the jobs front, recent data from Statistics Canada provide a glimpse of COVID-19’s toll on broadcasting jobs: Total weekly average employment numbers for all types of workers in television broadcasting fell by about 500 positions to 13,133 employees in 2021, compared to 2019. The losses were more dramatic in the radio sector, where employment declined by 1,307, to 10,115 last year.

More generally, the COVID-19 mapping project documented the temporary or permanent layoff of 3,023 editorial and non-editorial employees by 41 owners between March 13, 2020 and April 8, 2021. Of these pandemic-related cuts, 1,281 were subsequently deemed permanent. Information on how these job losses played out locally is limited because some companies with multiple outlets, including Glacier Media, Black Press and Corus Entertainment, refused or ignored repeated requests for details of labour cuts.

Government subsidies helped

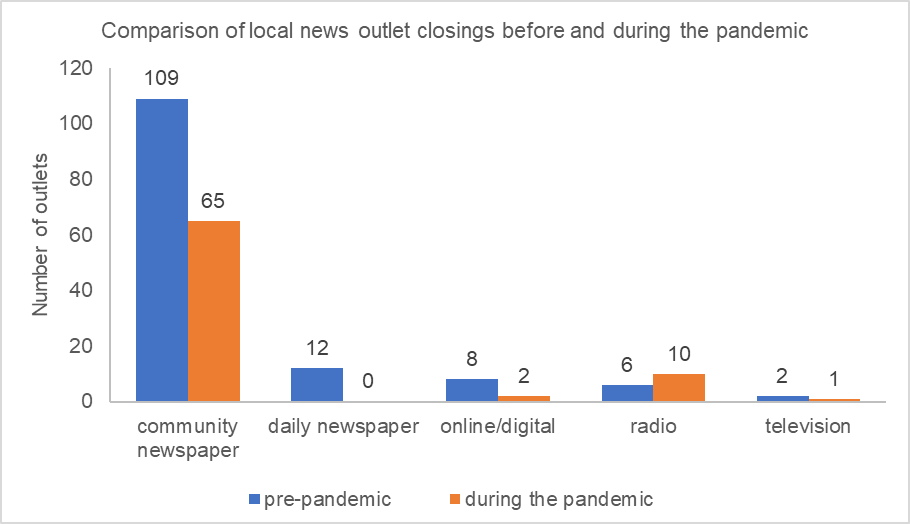

Federal COVID subsidies staved off the worst of the pandemic’s economic ravages: Data from the Local News Map, which tracks COVID-related closings as well as closings for other reasons, show that fewer local newspapers, television stations and online/digital news sites closed during the 29 months ending Aug. 1 than during a similar period before March 2020. As the chart below suggests, only the local radio sector experienced more losses.

NOTE: The Local News Map data tracks changes to local media only and includes closings for all reasons, not just pandemic-related shutdowns. The pre-pandemic data is for approximately 29 months from Oct. 1, 2017 to March 10, 2020; the pandemic data is for approximately 29 months from March 11, 2020 to Aug. 1, 2022. SOURCE: Lindgren, April & Corbett, Jon. (2022). Local News Map Data: Aug, 1, 2022. Local News Research Project

“I always say the dirty little secret of Canadian newspapers is that they coasted through COVID because the federal government paid for them,” Cox said, adding that the support meant the Free Press did not lay off staff. “A lot of newspapers that might otherwise have been in a lot of trouble, existential trouble, were not because the federal government kept them afloat.

“Now of course we’re into a situation where we have to figure out (if) we have strong enough business models to move forward.”

Federal COVID supports came in a variety of forms. Government spending on media advertising, much of it to inform Canadans about pandemic-related government services and safeguards, surged to $107 million between April 1, 2020 and March 31, 2021. It was $45 million in the previous year.

The federal Canadian Periodical Fund expanded to support a broader range of publications. Before the pandemic, community newspapers and magazines that met circulation and other eligibility criteria received about $75 million a year from the fund. This included about $15.5 million for 350 paid-circulation community (non-daily) newspapers and an additional $55 million for about 375 paid-subscription magazines.

During the pandemic, program eligibility expanded to include subsidies for free and low-circulation community newspapers and magazines. As a result, an additional $93.8 million was dispersed via the Canadian Periodical Fund during 2020-21 and 2021-22. This meant about 800 additional titles received financial support to offset the pandemic’s impact.

Like other Canadian businesses, news organizations also drew upon the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy, put in place to support employers facing financial hardship as measured by a certain level of revenue losses. The claim period ended in October 2021 but final CEWS payments were still being issued this spring. According to the Canada Revenue Agency, newspaper proprietors received $247 million in CEWS payments while television station owners collected $201.7 million and $96.7 million went to radio stations. Statistics Canada reported the majority of radio (65 per cent) and television (74 per cent) license holders received CEWS payments in 2020.

Media in Canada forced to acknowledge failures in equity, inclusion

The murder of George Floyd by police in Minnesota in spring 2020 sparked widespread demands for change, including in newsrooms and news coverage. Conversations about the overrepresentation of white journalists and news leaders and everything from problematic editorial practices to labour abuses quickly made their way to Canada.

Within weeks, journalists at the Globe and Mail called for legally binding language on workforce diversity and inclusion to be negotiated into collective agreements. Newsroom staff at the National Post challenged editors after the newspaper published a Rex Murphy column denying the existence of systemic racism in Canada. A news report based on leaked audio from a National Post town hall revealed there was little or no oversight of the column before it appeared online.

Students at Canada’s journalism schools, which have also been slow to change, also issued demands for action.

“Work that has been done in diversity, equity, inclusion, community work, some of which has been happening for a while in some spaces … it’s been very siloed,” said Sonya Fatah, assistant professor of journalism at Toronto Metropolitan University, co-lead on the Canada Press Freedom Project and former editor-in-chief of J-Source.

Changes during the pandemic included TMU’s introduction of a new course on reporting on Black communities and Carleton University’s establishment of the Carty Chair in Journalism, Diversity and Inclusion Studies, now held by Nana aba Duncan.

Overall however, progress has been slow, said Fatah, who is conducting research into journalism education initiatives related to diversity, equity and inclusion: “Students at these universities are angry, and it’s not that they’re just rebelling. They’re angry about paying for an education and seeing that they’re not getting the whole story.”

Transformation of journalism work

The pandemic years dramatically changed how and where journalists do their jobs, most obviously by pushing reporters and editors into remote work. It also created new momentum in the unionization of digital newsrooms, including the formation of bargaining units at places such as Canadaland and the National Observer. United Photojournalists of Canada, a new collective for photojournalists, emerged in 2020 to champion the many freelancers who worked on the front lines throughout the pandemic. The grassroots labour group also played a part in negotiating the first pay increase in a generation for Globe and Mail freelance photojournalists.

The COVID years were also a time of growth, opportunity and experimentation for digital-born publications. Data from the Local News Map show 38 new online local news outlets launched in the 29 months ending Aug. 1, compared to the 23 with a local focus over a similar period prior to the pandemic. Examples range from Afros in tha City, a Calgary-based collective dedicated to amplifying Black voices to Gameday London, which covers local sports in London, Ont.

“People are seeing the opportunity … and the need in communities everywhere,” said Farhan Mohamed, co-founder and CEO of Overstory Media Group. “The pandemic has probably helped to have those discussions … What is the best approach? There are so many different ways to go about it.”

In 2021, OMG launched with a stable of online, west-coast publications under its umbrella, including the Victoria-based Capital Daily and pledged to establish 50 local publications by 2023. Earlier this spring it acquired The Coast in Halifax and announced efforts to raise $5 million in venture capital to seed a North American expansion. The company currently lists 10 brands on its website.

University of British Columbia professors Mary Lynn Young and Alfred Hermida have been tracking new entrants to digital journalism in Canada to better understand their sustainability, funding and crucially, their missions. What they’ve found points to bright spots in the media landscape.

Many of the startups, said Hermida, are prioritizing more representative and inclusive journalism and responding to a “crisis of journalism as misrepresentation of communities and harms done to a range of communities that are not white and predominantly male.” It’s a theme explored at length in “Reckoning: Journalism’s Limits and Possibilities,” a book by Young and colleague Candis Callison published on the eve of the pandemic.

Young and Hermida identified 120 digital news launches since 2000. “What our results are showing and part of the intention behind the research is … to show that (the journalism industry) is evolving,” Young said.

The Local, as an example, started out as an experiment by the University Health Network’s OpenLab, a hospital-based initiative that explores new ways health care can be delivered and experienced. Huhyn said when The Local spun off into an independent nonprofit three years ago, he deliberately eschewed paywalls because the goal was to reach populations shut out of media coverage.

“Our focus isn’t world domination and growth,” he said. “It’s about doing local journalism really well.”

The vibrancy of the digital sector during the pandemic contrasts sharply with continued signs of retrenchment in the newspaper industry, where the permanent closing of bricks-and-mortar newsrooms also transformed journalism work. Our limited survey identified two dozen daily and weekly newspapers where reporters and editors have been told they will be permanently working from home. The list of newsroom-free newspapers includes TorStar’s Peterborough Examiner, Waterloo Region Record and St. Catharines Standard and Postmedia’s Kingston Whig-Standard and Sault Star. Brunswick News, which was acquired by Postmedia earlier this year, shut down 10 community newspaper offices in New Brunswick in May 2020.

Jim Poling, editor-in-chief of the Waterloo Region Record, said concerns about how to support younger reporters who will never set foot in a newsroom prompted him to assign mentoring duties to a senior copy editor. “We’re more than two years into the pandemic and we had to find structural ways to stay on top of that in an industry that is constantly shifting,” he said.

Thriving mentorship programs

Poling is not alone in his concerns. In its early days, the pandemic forced the temporary cancellation or postponement of internship programs at Postmedia, the CBC and other media organizations — programs that students and other journalists starting out in the business rely on for crucial experience and in many cases, fulfillment of degree requirements.

One response has been the emergence of independent mentorship programs that help early-career journalists who don’t have regular contact with more experienced reporters and editors.

Brent Jolly, president of the Canadian Association of Journalists, said the association used to set up mentorship opportunities once a year at its in-person national conference. Since mid-2020, however, it has been taking virtual applications multiple times per year and has paired more than 400 mentors with mentees. If the pandemic has a silver lining, Jolly said, it is that most programs now run virtually, which means journalists are matched with the most appropriate mentors regardless of where they live.

The next chapter

So what does the future look like?

Revenue generation will remain an issue. Most notably, the end of CEWS, which provided $545.4 million to newspapers and radio/TV stations during over 19 months ending in October 2021, represents a significant loss of cash for many news organizations.

Over that period, for instance, Glacier Media Inc., which operates newspapers in western Canada, reported $21.3 million in CEWS payments for employees in its media and other divisions. Postmedia Network had collected $63.3 million in subsidies as of August 2021.

CEWS was never meant to be permanent. But the disappearance of those payments, combined with the uncertain prospects for a major recovery in advertising, raises questions about what future revenue streams will look like.

Government aid programs that predate COVID-19 will be one source for as long as they last. One of the more significant pots of money, for instance, is the Canadian journalism labour tax credit announced in 2019 as part of a $595 million federal aid package for news media. It will boost company balance sheets by $360 million over five years. But unlike CEWS, which was offered to all companies experiencing revenue declines beyond a certain level, the tax break is only available to qualified journalism organizations. And unlike CEWS, which applied to wages for all employees, the 25 per cent refundable tax credit applies to newsroom employees only. When all is said and done, the measure is expected to generate $8 million to $10 million a year for a company like Postmedia based on its current newsroom staff levels.

The Trudeau government’s Local Journalism Initiative, worth $70 million, is another revenue source. The LJI, put in place for five years and scheduled to end in March 2024, pays the salaries of journalists who report on undercovered issues, groups or geographic areas. In its first two years, it funded the hiring of 777 journalists, according to data provided by the Department of Canadian Heritage. Depending on the year, between 250 and 300 different news organizations benefited.

Federal legislation, if it is passed this fall, will also generate revenue by requiring digital giants like Google and Facebook’s Meta Platforms to pay news publishers for use of their content. But as Bill C-18, the Online News Act, gets closer to becoming law, Meta is making news less of a priority and just announced it will not renew the three-year deals to pay for content it voluntarily struck with U.S. publishers in 2019. Independent news publishers in Canada, meanwhile, warn the legislation in its current form lacks transparency and may exclude smaller publishers that aren’t part of big chains or corporations.

Non-profit and, to a certain extent for-profit news media, are also tapping into philanthropic support. Since 2019, for instance, faith groups in Winnipeg have contributed money to cover the cost of religion coverage at the Winnipeg Free Press. Just recently the Winnipeg Foundation agreed to fund a Manitoba-based environment reporter who is producing stories for The Narwhal and the Free Press.

But with only The Narwhal, The Local and six other registered journalism organizations authorized to issue tax receipts and qualify for direct funding from foundations, the reality is that the vast majority of news organizations in Canada can’t easily secure philanthropic support because they are for-profit operations.

Cox, for example, said the Winnipeg Foundation wanted to give the Free Press $1 million to support coverage of the local arts community over five years, but finding a way around the Canada Revenue Agency rules was challenging. That, combined with the mass cancellation of arts events due to the pandemic, prevented the project from getting off the ground.

The Ottawa Community Foundation, meanwhile, set up a Journalism Endowment Matching Program with $25,000 to be divided among five news organizations. Participating news outlets had to raise a matching $5,000 and be either a registered journalism organization that qualifies for charitable donations or a for-profit that partnered with a local charity. The for-profit news outlets found it challenging to find local charities to work with in a way that satisfied tax rules, said Janet Adams, the foundation’s manager of philanthropic services. Since the program launched in mid-2020, only two local media outlets have signed on.

Cox warned that relying on government programs and charity for revenue comes with risks: “They’re here for a year or two and then they are gone,” he said.

Huynh, The Local’s editor-in-chief, sounded a note of caution about government supports for other reasons, noting that they have the potential to distort business models. Startups that have relied primarily on freelancers for content, he said, are now hiring full-time staff to qualify for the labour tax credit: “It is really dictating the structure of how content is produced … to the detriment of a lot of startups,” he said. “In the early stages, you don’t want a lot of fixed costs.”

In a future where news organizations will clearly be reliant on multiple revenue sources, tapping readers for support will be even more important. There is plenty of room for growth: While the number of Canadians who pay for online news or accessed paid online new services has increased steadily since 2016, it is still only a paltry 15 per cent.

“We knew (pre-pandemic) that building the reader revenue model was key to … the future,” Cox said. “But again COVID sped everything up.”

At the Winnipeg Free Press, relationship building with readers during the pandemic included the launch of virtual movie nights, a book club highlighting local authors, a brew club and virtual tasting sessions that involve shipping beer samples to members’ homes, a fall community supper and outreach to communities that have typically been undercovered.

Cox said the paper’s digital subscriptions are growing but at a reduced pace compared to earlier in the pandemic. And the long downward trend in print subscribers continues to be a challenge: “We’re getting more and more to a core group who really likes the experience and really likes newspapers and really wants the newspaper to continue, but that’s a smaller and smaller group,” he said.

At The Narwhal, by comparison, the record-high traffic at the beginning of the pandemic translated into record-high support from its members. The growth in revenue, which disqualified the publication from CEWS, meant 14 new employees could be hired over the past year, bringing the staff complement to 23.

“There’s a lot of promise when publications build their success around the relationship with readers,” Gilchrist said. To expand its audience, The Narwhal used its free newsletter as well as online events that attracted upwards of 1,000 participants during the pandemic. Its focus on environmental issues makes it easier to recruit “members” who contribute an average of $13 a month, she said, noting that about 40 per cent of revenue now comes from memberships while philanthropy generates the rest.

“People always say there’s no philanthropic support for journalism in Canada (but) it literally wasn’t possible until like a year ago, so I think we’ve got to give people a chance,” Gilchrist said.

“The future looks very bright” for digital news, she added. “There’s just a lot of high quality work coming out of the digital newsrooms.”

While there are clearly digital winners, launching an online news site still isn’t for the faint of heart.

“When creating a new digital journalism organization, the hard part isn’t so much the journalism, it’s everything else,” said UBC’s Hermida.

Relying upon readers and viewers, for instance, is easier for digital plays like The Local in the highly populated Greater Toronto Area, or The Narwhal, with its environmental coverage that appeals to a national audience. Attracting paying supporters is more difficult, however, for sites that serve up hyperlocal content to smaller or less affluent communities: There are fewer people to appeal to for money and fewer potential attendees for events, assuming smaller news organizations even have the capacity to organize events and attract the sponsorship dollars associated with them.

The uptick in digital startups also isn’t a pan-Canadian phenomenon. Of the 38 local news sites launched during the pandemic, there were 21 in Ontario, 12 in British Columbia, three in Alberta and two in Quebec.

Looking to the future, the diminishing confidence in news media is another challenge that isn’t going away. Newsrooms are signing onto global efforts such as the Trust Project, the Trusted News Initiative and the Journalism Trust Initiative. But getting to the root of the problem will require more than public commitments to internationally agreed upon standards of transparency and news-gathering practice.

Issues that need to be addressed include the many shortcomings of an industry that has been overly deferential to the police and other official sources and too willing to embrace dominant narratives while ignoring or misrepresenting racialized, Indigenous, genderqueer, disabled and poor communities.

Although government aid has in part staved off the immediate economic crisis, it has also fueled attacks from critics who argue it is antithetical to independent journalism. These days, those who promote the fake news narrative are weaponizing the funding in a bid to convince people to turn against traditional news sources.

Finally, with a seventh wave of COVID-19 infections underway in much of the country, the pandemic story is still unfolding. Fiona Conway, who stepped down as RTDNA president in June, said many journalists are still working remotely even if they have newsrooms to return to. With every new wave, she said, broadcasters struggle to get shows on the air because so many people call in sick.

“It’s not over,” she warned.

April Lindgren is the principal investigator for the Local News Research Project at Toronto Metropolitan University’s School of Journalism.

Christina Wong is the data analyst, GIS technician and website administrator for the Local News Research Project.

Steph Wechsler is J-Source’s managing editor.