A fourth-generation newspaper rides the waves of change

This series was funded by readers like you through donations to the J-Source Patreon and FutureFunder at Carleton University.

In the summer of 2018, Angela Long embarked on a 22,000-kilometre journey, traversing eight provinces and a territory – from Dawson City, Yukon, to Cape Breton, N.S. – to learn from residents, reporters and experts about journalism’s importance in rural markets. In this series, she tells the stories of local news survivors and the roles they play in bolstering their communities.

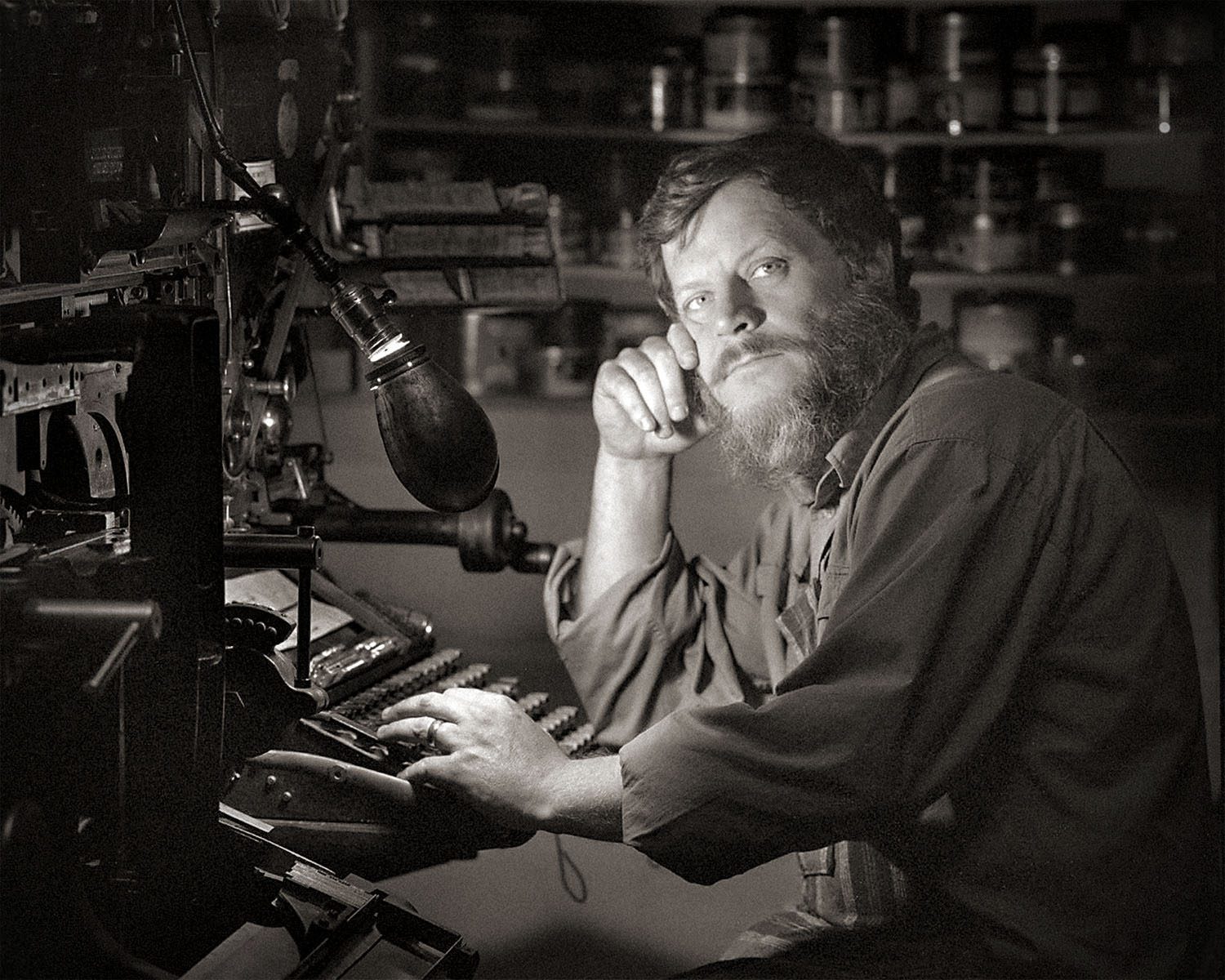

“You’ve heard the expression, as heavy as lead?” Richard C. Holmes says, bending to pick up a long, slender silver bar from beneath the Linotype Model 8. “Here you go.”

The 66-centimetre long lead alloy ingot, otherwise known as a “pig,” is cold to the touch and much heavier than it looks. Holmes laughs as it clanks to the ground, scattering silver-coloured shavings left over from past demonstrations of the hot metal typesetting machine – deemed “the eighth wonder of the world” by Thomas Edison – to local school kids. The concrete floor sparkles where Holmes, third-generation publisher, and until recently, editor of the Provost News, once transformed molten lead into words.

Other Linotype machines, Elektron models once worth upwards of $10,000, met different fates. “We took a sledgehammer to those beautiful machines, ” he says of what he calls the “Cadillac” of Linotypes. “It was awful what we had to do to them, but that’s progress.”

Pig ingots, pots of coloured ink, a hand-driven printing press, drawers containing compartments for an alphabet of metal-cast and wooden letters. The black-and-white facade of the 109-year old newspaper on Provost, Alta.’s main street, which simply says “The News,” does little to advertise the treasures within.

After the newspaper’s more than a century of riding the waves of change – including two world wars, a 1946 fire that destroyed the paper’s office and a shift from an agricultural-based economy to a cycle of oil booms and busts – Holmes isn’t too concerned about the last decade of newspaper industry decline. From its first issue as the Provost Star on March 18, 1910 (where the front page said “The press came”) to the paper’s 100-year anniversary edition in 2010, an estimated 5,000 editions had been delivered to the residents of this prairie town in east central Alberta. For 90 continuous years, since Ed Holmes purchased the paper in 1929, the Provost News has stayed in the family. But as the population shift from rural to urban Alberta continues, the paper – serving nine other towns, villages and hamlets in the district, plus two communities beyond – may be facing its biggest challenge yet. In tandem with the area’s shrinking population, circulation numbers have decreased by a third in the past five years.

The “hollowing out” of rural Canada

Population decline in rural Canada isn’t breaking news. In 1861, 84 per cent of the population was classified as rural. Now less than 20 per cent of Canadians live in what’s defined as rural or small communities. Strengthening Rural Canada: Why Place Matters in Rural Communities – a 2016 report funded by the federal government’s Adult Learning, Literacy and Essential Skills Program – warns that “we are reaching a critical hollowing out point in many rural communities.”

The Town of Provost, however, remains optimistic. It’s “a thriving community geared for growth,” the municipality’s business and community profile says, known for its greenhead duck hunting, Bodo Archaeological Site and the annual Splash and Smash. The profile boasts of a 12-hole golf course, a “legacy” of NHL stars, a livestock exchange that handles over 90,000 head of cattle a year, a Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce branch that’s been in the same location since 1908, and a Hollywood movie – Beyond the Heavens – filmed on location by former L.A. Law star Corbin Bernsen.

Holmes is also optimistic. Nearly 50 years in the business has taught him about the cyclical nature of media. He remembers talk that radio would destroy newspapers, then it was the television, next, the internet. Though the internet has played a role in decreasing circulation rates, he says, as people get older, they value the paper more. They want to know more about property taxes, schools, health care. They want to see their kid’s photo in the paper. It’s for this reason that, despite a circulation drop from 1,862 in 2014, to 1,258 in 2018, Holmes says he sees “more of the same” in the paper’s future, as long as there’s support from advertisers. He also feels supported by a network of Albertan weekly newspapers, whose history stretches back to 1880, 25 years before Alberta was even a province. Independent ownership, in some provinces and territories a relic of the past, remains relatively strong in Alberta. More than 40 per cent of the province’s community newspapers are classified as independents, according to News Media Canada reports, compared to 12 per cent across the provincial border in B.C.

Despite how things may look, owning a small-town newspaper is still a thriving business, says Holmes. It remains a product valued by the people who arrive Tuesday morning asking for a copy, before the papers are even unbundled. Advertisers call from 70 kilometres away in Wainwright.

But statistics don’t bode well for the Municipal District of Provost. While the population of Alberta grew by 11.6 per cent between 2011 and 2016, the district’s population declined by 3.6 per cent. In 2006, 2,547 called the area home. By 2016, the number of residents had dwindled to 2,205. A January 2019 article in the Provost News says the number of births in 2018 at the Provost Health Centre decreased by 22 per cent compared to 2017. Births since 2008 have dropped by nearly 60 per cent. According to 2018 Government of Alberta population projections, the majority of the province’s growth, at an average annual rate of 1.4 per cent, will occur in urban areas. By 2046, four out of five Albertans will live in the Edmonton-Calgary corridor – an area that covers six per cent of the province’s land area yet contains 76 per cent of its population. Provost is located in one of the three census divisions (out of a total of 19) projected to experience the lowest growth rates in the province.

A 2015 Canadian Rural Revitalization Foundation State of Rural Canada report, which begins with the line “We have been neglecting rural Canada,” examines challenges faced across the country. In Alberta, a “retreat” from rural communities beginning in 1971 – caused by a mix of policy shifts, unfulfilled promises and bad investments – paved the way for a “transition to an urban and corporate-focused Alberta.” Factors such as a decrease in the number of farms and an over-reliance on oil have led to strains on rural infrastructure, exacerbated by both a smaller tax base and a “boom and bust” population cycle of oil workers who may use a municipality’s services yet direct their income elsewhere. This coupled with the 2015 election of an NDP government with little rural support, warns the report, creates the “potential for a large urban-rural divide to emerge.”

Such a divide, the report concludes, comes at the cost of ignoring the untapped potential of rural Canada – a place at the “front lines” of environmental issues such as sustainability and conservation, and reconciliation with First Nation and Aboriginal communities. A place, they say, that has “much to teach us about building strong communities and resilient economies in the 21st century.”

Tales of oil, anger and just doing your job

It’s the last day of business before the Provost News closes for its annual two-week summer holiday. Every 15 minutes or so, the phone rings, or the chime on the front door tinkles. Holmes looks out the octagonal windows of his office onto the town’s main thoroughfare, where vehicles – mostly pickup trucks – park at 45-degree angles. Just a few blocks away, canola fields stretch toward the horizon and the growl of oil rigs on Highway 13 joins the low rumble of distant thunder.

Although the agricultural industry is still very important, says Holmes, “Alberta, right or wrong, lives on oil. That’s the way we’ve done it since the 1940s or ’50s.”

Like any good Albertan, he knows the story of the Leduc oil find, and the legendary Dry Hole Hunter, who once stayed at the bygone Provost Hotel. There’s lots of oil around Provost, according to Holmes, farmers potentially sitting on millions of dollars worth of crude. “We are suffering right now because of the price of oil. We feel it here.” He talks of smaller oil companies that have “quietly vanished, locked the door.” Declining student enrolment rates have reduced the Provost Public School’s teaching staff. A few local shops, in a town where several businesses have existed for three to four generations, have closed.

“If you want to get a feel for rural Alberta,” Holmes says, “there’s a lot of anger, quite frankly.”

While Holmes says he isn’t “anti-city,” he’s tired of an attitude in which city folk seem to forget that “we grow the cattle, we grow the wheat, barley, corn, peas. We grow oil. We grow gas.” Such an attitude, he says, adds to the widening the gulf between urban and rural residents.

Now “you’re the bad guy if you drive a car,” Holmes says, referencing the NDP government’s push to create a more carbon-conscious province. “’Just take a bus,’ they say. Did you see any buses around here?” Holmes laughs. “Send me the bus schedule, Mrs. Premier, and we’ll see how that goes.”

Holmes talks about being diagnosed with cancer last year and the numerous trips he makes more than 140 kilometres one way for treatment. Though he is grateful for this treatment, he says the carbon taxes levied by the province on gasoline make him feel like he’s being penalized for living in a rural area. “We’re getting away from newspapers,” he says. “But there’s a connection there.”

The connection can be found in the content of the Provost News. Columnists writing to lament lost revenue due to the provincial carbon levy, the “anything but transparent” provincial equalization formula, the transformation of an agricultural fair into an “entertainment package.” Holmes opens the July 4 issue to page two of the 20-page paper where a cartoon of a woman eating breakfast and reading the paper says to the man across the table, “Notley and the NDP are going to set up a ‘hate crime unit.” The man responds, “‘Scuse me? That’s over the top! We don’t hate the NDP. We just want them the #@!! out of office!!”

But politics aren’t Holmes’s main concern. He has a paper to put out. The paper that has sustained him and his wife and children, and his father’s and his grandfather’s families before them. While the Town of Provost’s latest slogan is “Dreams Create the Future,” for Holmes it’s the traditional rural Albertan values of hard work and innovation that will see them through.

“I think, to be quite blunt and honest, you have to make money, you have to survive, and you have to sell advertising and the only way to sell advertising is to run good news and keep up to date,” he says.

From hot lead to cold print to desktop publishing, Holmes has been keeping up to date since the ’70s. He printed in colour in tandem with, or maybe even before, he says, the big urban dailies, attended conferences where people such as Doctor Tomorrow presented new inventions. “He stood up on stage and told all of us newspaper people that somebody has developed a camera that requires no film,” says Holmes.

News of the digital camera from Japan “whetted my appetite,” he says, and he remembers when an episode of the CBC 11 o’clock news aired a story about a big city newspaper being the first to use digital photography. “It was breaking news but we’d been doing that for months,” he says, adding that it was one of those “look at what the big guys did and never mind me” moments, moments that are all too common for those who live in rural Alberta.

Holmes was named editor by his father in 1973 when he was just 22 and the average age of their newsroom staff was 19.

And “I’ve been stuck here ever since,” he laughs.

Holmes won’t be stuck at the Provost News much longer. On March 1, 2019, Jill Sherring, Holmes’s 33-year old daughter, was officially named editor. In a telephone interview on her first day on the job, Sherring sits in what was once her father’s office. Earlier that morning she had hung up her winter coat on the back of the door and her father had hung up his in the staff area. “It’s still kind of surreal, actually,” she says of being the new boss. “It hasn’t quite sunk in yet.”

Since 2012, Sherring, who studied visual communications at Medicine Hat College, has worked at the paper as a reporter, typesetter and photographer. She recalls a photo of her as a three-year old, with a stack of newspapers in her arms. “It must be in my blood,” she says.

First drafts of history

Back in the summer of 2018, Holmes was just happy that Sherring was “showing some interest” in the paper.

He stands up, walking past his daughter’s desk. “The fourth generation,” he says, then points to the children’s toys scattered on the floor. “And the fifth, I hope.”

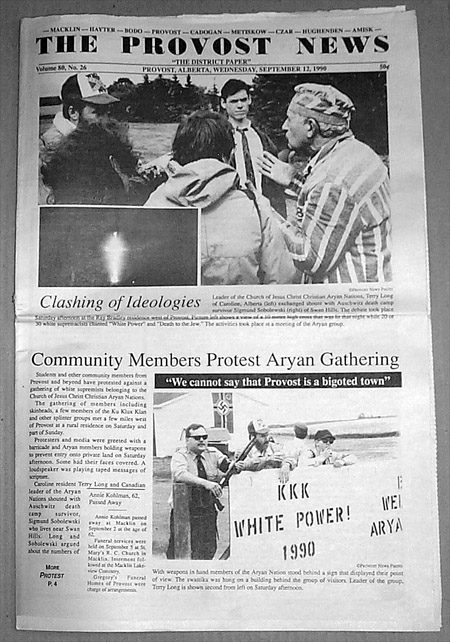

The screensavers and walls of the Provost News office display photos of the surrounding landscape: the northern lights, a snowshoe hare in Holmes’s garden, a field of wheat dotted with deer. Holmes stops in front of a poster for an award the Provost News won in 1990, saying a few words about the Ku Klux Klan and a “couple things” he wrote.

The weekend when the Alberta Aryan Fest showed up, some of whom were armed, six kilometres northwest of town, flying Nazi flags, wearing white Klan-style robes and burning a 30-foot high cross, “was quite a traumatic weekend for our community,” Holmes says. The Provost News got to work, publishing photos, articles, letters to the editor and a scathing editorial. Homes later testified about the events of the September 1990 weekend at an Alberta Human Rights Commission hearing.

In Alberta’s Weekly Newspapers: Writing the First Draft of History, author Wayne Arthurson credits media outlets such as the Provost News with “reducing the promotion of hatred in the province” because of the hearing’s outcome – the enactment of section 3 of the Alberta Human Rights Act, which makes it illegal to discriminate against people based on their religious beliefs, race, colour, ancestry or place of origin through the use of signs and symbols.

Nearly thirty years later and Holmes says he is still proud of that weekend, which “showed what Provost was really made of.”

The butcher, the medical staff and the hardware guy – it’s all community

Even though it’s just past noon, the Provost sky grows dark. Holmes warns of thunderstorms. The phone has stopped ringing, and soon it will be time to switch off the lights and lock up until the next issue.

When asked if, after 109 years, the Provost News may have played a part in building a community so determined to survive, Holmes hesitates.

“Maybe,” he says, “but not any more than the hardware guy or the butcher or the people who work at the medical centre. I think the paper is an important part of the community. I’ll put it that way. I’ll say that much.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated at 11:42 a.m. ET on March 8, 2019 to correct that the Provost News papers are unbundled on Tuesdays rather than Wednesdays.

Angela Long is a freelance journalist based in Toronto currently working on a book about rural journalism in Canada.