Delivery by the thousands beneath glacier-clad peaks

This series was funded by readers like you through donations to the J-Source Patreon and FutureFunder at Carleton University.

In the summer of 2018, Angela Long embarked on a 22,000-kilometre journey, traversing eight provinces and a territory – from Dawson City, Yukon, to Cape Breton, N.S. – to learn from residents, reporters and experts about journalism’s importance in rural markets. In this series, she tells the stories of local news survivors and the roles they play in bolstering their communities.

“You don’t need to worry about bears around here,” the Rosebery Provincial Park attendant says, pointing to the sun-dappled cliff face at the back of Site #18. “It’s the cougars you have to watch out for.”

She unloads firewood from her truck. A creek rages along the edge of the West Kootenay campground, the rush of glacial meltwater so powerful it dislodges boulders, bouncing them like bowling balls downstream. “We don’t recommend walking alone,” she says, raising her voice above the din.

It’s mid-June – a time of wild roses and lupine, and tourists arriving to scale glacier-clad peaks, kayak pristine lakes and explore ghost towns and hippie enclaves. The sound of a mountain range disgorging millions of litres of meltwater fills the Slocan Valley.

And, year-round, for 27 years, the words of the Valley Voice – a twice-a-month, free newspaper based in New Denver, B.C. – have also resounded throughout these mountains, and those beyond. Despite an area of coverage straddling three valleys, a grueling work schedule and a lack of support from federal funding bodies, the Valley Voice’s love of this land and its people keeps the presses rolling.

A rural-mountain-valley newspaper that doesn’t fit into the box

It’s 11 o’clock in the morning, just 11 hours since publishers Jan McMurray and her partner Dan Nicholson sent the latest edition of the Valley Voice to the printers, but they don’t have much time to relax.

“Because we own it, we’re the chief cooks and bottle-washers as well,” says McMurray, her hands folded on a long slab of pine table, her favourite item in their house. As the paper’s chief editor and main reporter, she outlines the days ahead – bookkeeping, distribution, story planning, interviews.

“I’m 55 years old and I still have a paper route,” Nicholson says with a laugh, glancing towards a picture window that glows green with the surrounding forest.

Tomorrow morning, Nicholson will drive 46 kilometres to Nakusp, load their Jeep with 7,600 newspapers delivered by freight from the printing press in Vernon, and return to the office where they will sort 6,420 papers into piles according to their post office and valley: Slocan, Arrow Lakes, North Kootenay Lake. The next day, Thursday, they will each go their separate ways to hand deliver more than 1,000 papers to businesses and services throughout the valleys.

Even in winter, when darkness comes early – falling on nearly 3,000-metre high peaks and icy roads that twist through sheer rock faces to create what one clerk at New Denver’s New Market Foods calls “a death trap” – the Valley Voice always delivers.

Such geographic extremes might cause other publishers to choose the comforts of their desk instead and go digital. But in rural areas where internet service “isn’t the best,” says McMurray, and their main demographic is senior, going digital just doesn’t make sense. More importantly, “it’s a capacity issue,” she says. “To do an online newspaper in conjunction with what we do right now? It’s just too much.” And then, from a business model perspective, “how do we monetize digital?” she asks. “It’s just extra work with no extra income.” For now, they will continue to maintain their website and post a PDF-version of the paper every Friday.

Besides, both Nicholson and McMurray say they enjoy their outings. “That’s how we keep our relationships up with our advertisers,” says McMurray, chatting, getting to know each other face-to-face in restaurants, seniors’ centres, hotels, shoe stores – in all the drop-off points along their delivery routes.

Good relationships with their hundreds of advertisers throughout the three valleys is essential to cover the $1,000 printing and $1,000 Canada Post bill every issue. If at least half their paper isn’t advertising, Nicholson says, they lose money.

It’s precisely this quality – being free – that prevents publications such as the Valley Voice from being eligible for the Aid to Publishers program of the Canadian Periodical Fund, a subsidy program launched in 2010 for community newspapers and magazines to, according to its website, “enable them to overcome market disadvantages and continue to provide Canadian readers with the content they choose to read.” Other publishers in the province, (primarily Black Press, which, according to the latest News Media Canada reports, owns 78 of the 127 community newspapers in B.C.) received more than half a million dollars in 2018 for 27 of its B.C.-based publications, including $21,479 for the Revelstoke Review (circulation 1,188), and $42,391 for the Grand Forks Gazette (circulation 2,038), both within 200 kilometres of New Denver. One Black Press paper in the Valley Voice’s coverage zone, Nakusp’s Arrow Lakes News (circulation 427), received $9,987.

“They’ve got to change their rules,” says McMurray. “It’s just ridiculous.” Several years ago she sent an email of complaint to the Canadian Periodical Fund. “I said, ‘look, here’s our situation … c’mon, you’ve got to be a bit more flexible’ and they wrote back and said, ‘absolutely not.’”

To change the paper from being free to paid circulation, as required by the Canadian Periodical Fund, would mean changing their whole system, says Nicholson. In addition, in the rural pockets of these valleys, where four-wheel drive pickup trucks aren’t just for show, being able to tell advertisers that their ads will reach more than 6,400 mailboxes is a huge boon.

When it comes to federal funding, says McMurray, “We don’t fit into the box.” So, the Valley Voice, one of only a dozen remaining single-title independent publishers left in the province, will continue to follow its own path. Last year, Nicholson says, was a good year. In addition to drawing a monthly salary of $2,000 each through their business Valley Voice Ltd., the paper saw a profit of $10,000.

But neither McMurray nor Nicholson is in this for the money. They just want to be here.

Underbidding Black Press and keeping it local

When the couple was expecting their first child and moved to the Slocan Valley from Vancouver in 1993, they had no idea of how they’d make a living.

“But Jan told me she couldn’t live if she wasn’t surrounded by mountains,” says Nicholson. “Kinda strange for someone from Mississauga,” he says, scratching his beard. “You know how some women say things like ‘size doesn’t matter’? Well, when it comes to mountains – ” McMurray laughs.

After 10 years of doing odd jobs to stay in the place they loved, including working at local cafes or at the Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre, the paper came up for sale.

Nicholson was interested “because I have no other employable skills,” he says.

McMurray saw a way out of a decade of precarious employment. “Really, what you have to do here is start your own business,” she says.

Owner Bonnie Greensword, who founded the paper with Katrine Campbell in 1992, told them Black Press had offered her $85,000. They offered her $65,000. “Let’s split the difference,” Greensword said, preferring to keep the paper independent and locally owned.

At that point, both Nicholson and McMurray had a few journalism stints between them. McMurray had studied at Carleton University for a year when she was 18 (a time when shorthand and 60 words-per-minute typing skills were a prerequisite) before quitting to travel the world. Nicholson had started the Souris Valley Echo in his mid-20s, a workers’ co-operative paper, in his hometown of Souris, Man. After they met, they’d published a “left-wing” quarterly with a group of friends, the Big Picture, where they sold ads, wrote stories and did layout and graphic design. The Vancouver-based publication folded after a year.

Nicholson goes out to the porch for a smoke, passing 20-kilogram bags of cat food, meant for Anubis, their cat who – evidence suggests – was killed by a cougar. McMurray rummages around for past issues. The latest June 14, 2018 issue contains stories about helicopter-based adventure tourism, healthy aging in New Denver, physician recruitment. She flips through the 24-page paper, past notices for a wildfire and climate change conference, a strawberry social at the Yasodhara Ashram, Columbia River Treaty community meetings. She stops at what she says is the most popular section, two full pages of letters to the editor called “Voices from the Valleys.”

“Are you guys getting hungry?” Nicholson calls from the back porch.

The role of the local paper in a shifting economy

Trying to make money owning a newspaper in the Slocan Valley has always been a challenge. In Newspapers & the Slocan in the 1890s, Canadian geographer and University of British Columbia professor emeritus Cole Harris highlights 17 newspapers found in and around the Valley, during the decade after prospectors discovered deposits of galena (silver-lead) ore in 1891. Despite the remoteness of the valley, and having to lug printing presses up mountain passes or onto sternwheelers that once traversed Slocan Lake, mining and newspapers seemed to go hand-in-hand.

“To establish a town site and erect a few buildings was, in effect, to attract a newspaper,” Harris wrote.

None of the newspapers were much of a financial success, however, even those owned by Robert Thornton Lowery (aka Col. Lowery) – a “crusading pioneer journalist,” with a penchant for “naked racism” as he’s described by the Sandon Historical Society – whose 10-year stint publishing the Ledge in New Denver, a town he called “dead to enterprise,” ended with the words, “We would rather be ground to death under the pitiless wheels of commercial competition than rust to the finish, like a scrap of iron on the hillside.”

On any trail leading out of New Denver and into the Slocan Valley, scraps of rusting metal – from the abandoned equipment of an old mining settlement where the smell of tar lingers on rotting railway ties, to the steel cables of a former logging sort yard – attest to a century of decaying industry.

The transition from a resource-based economy to a more tourism-based one unites all three valleys covered by the paper, says McMurray, now from a table in the corner of the Apple Tree Sandwich Shop.

The crowd at the Apple Tree ebbs and flows, always seeming to pool for a moment at the table in the corner. The Valley Voice owners chat to all who stop. McMurray flashes what Nicholson calls her “1,000-watt smile,” over and over.

“Our communities can really learn a lot from each other,” says McMurray, who does her best to ensure either herself or one of their freelance journalists covers each of the five village councils, numerous public meetings and the monthly regional district meeting (their coverage zone encompasses three regional areas). In such a critical time of change, says McMurray, where important issues such as the environment, health care, and, ultimately, the survival of rural communities are at stake, she says, they take their roles as the providers of accurate and clear information very seriously.

Most importantly, the Valley Voice shows residents that though they may have differences, their love of this place nestled in the mountains a day’s drive from either Calgary or Vancouver trumps everything.

“The paper a unifying tool,” she says.

The power of community support, a cold margarita and a view

Change is in the air as you walk through the streets of New Denver, where historic buildings painted in pastel hues of butter yellow or periwinkle blue that once housed bookstores or hardware stores now bear for sale signs. Wild chicory springs up through the sidewalk cracks. A piece of what looks like tumbleweed bounces its way westward, towards the sparkly Slocan Lake at the base of Sixth Avenue.

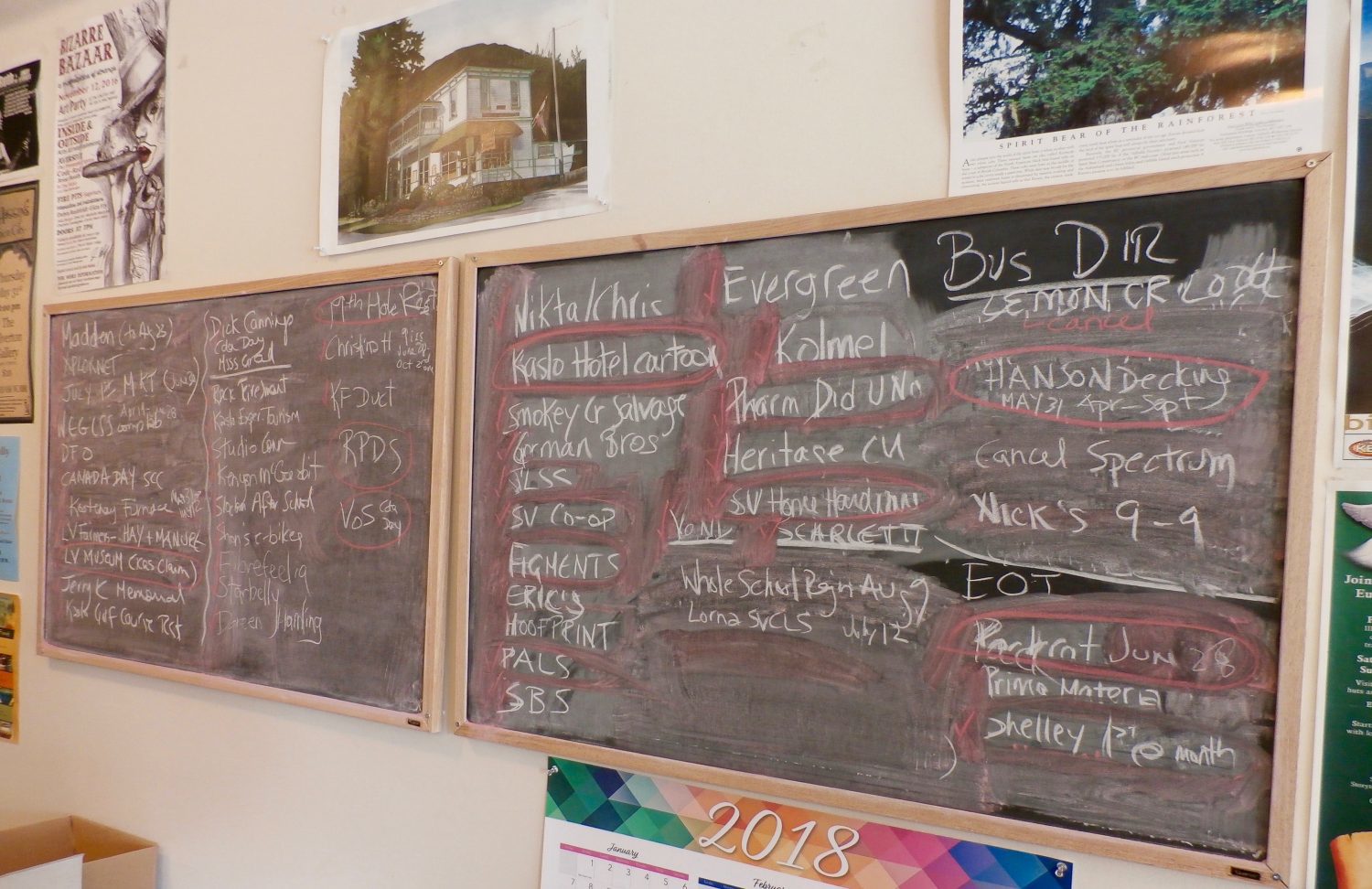

But at the office of the Valley Voice, messages await on the answering machine, and the phone starts ringing the moment McMurray and Nicholson unlock the door. “Hello, I’d like to place an ad for the upcoming Antiques Roadshow,” says the first caller, filling a space decorated with plants, a collage of event posters dating back to the ‘90s and a classroom-sized blackboard scrawled with their “to-do” list.

While the local economy may be in a state of transition, the paper has managed to maintain a steady stream of advertisers. Having expanded their coverage area shortly after buying the paper in 2003, their circulation numbers have even seen an increase from approximately 6,200 to 7,600.

“Our newspaper seems to be getting bigger,” says Nicholson. “We’re selling more ads.”

In a February 2019 email, Nicholson says 2018 was “an exceptionally good year” with a profit of $33,000. He attributes their success to municipal elections, where the five villages and Regional District of Central Kootenay they serve are required by law to advertise in generally-circulated newspapers.

In the back of their office, a fridge filled with cans of lime-flavoured margaritas awaits. Nicholson cracks one open. “Cheers!” he says, showing off the boxes of archives and old layout tables in the converted fire hall he and McMurray purchased from Greensword.

McMurray hangs up the phone and stands behind the front counter. A handmade basket, a gift from a reader, sits in front of her, the words Valley Voice: 25 Years Proud written on a piece of birchbark. It’s these kinds of gestures, she says – along with voluntary paid subscriptions, cards, and messages of support from locals appreciative of the paper – that have kept McMurray and Nicholson driving up and down their bean-shaped valley for 16 years.

Outside on Sixth Avenue, Nicholson lights up a cigarette, turning to face mountains that encircle New Denver like an embrace. A glacier glints in the late afternoon light; the lake turns from jade to sapphire. Nicholson exhales, and walks back inside.

Angela Long is a freelance journalist based in Toronto currently working on a book about rural journalism in Canada.