Democracy and the decline of newspapers

By Dale Eisler, Senior Policy Fellow, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy

In the 18th century, Thomas Jefferson famously wrote that if the choice were government without newspapers, or newspapers without government, he would choose the latter.

Today, almost two-and-half centuries later, Jefferson’s observation might actually be tested. The great disrupting influence of digital information and communications technology made ubiquitous by the Internet has undermined the commercial foundation for print media. Everywhere you look, newspapers are in retreat. Pick your measurement: Paid circulation? Shrinking; Advertising revenue from print? Evaporating; Newsroom staff? Disappearing; Long-term viability? In jeopardy.

A website appropriately named “newspaperdeathwatch.com” lists 13 major U.S. daily newspapers that have closed since 2007. Among the Canadian casualties are the Halifax Daily News, Nanaimo Daily News and Guelph Mercury. In Montreal, La Presse ended its printed weekday publication and now only produces a weekend print edition. It maintains a digital publication on its website.

Appearing before a the House of Commons Heritage Committee last May, the CEO for Postmedia Network, Canada’s largest newspaper chain, sounded an ominous tone about the future of newspapers. “The erosion of print revenue has been dramatic. The picture is ugly and it will get uglier. You’re going to find there will be a lot more closures,” Paul Godfrey said. The same grim opinion was expressed by John Honderich, chair of Torstar when he appeared before the committee. “My message to you is a simple one: there is a crisis of declining good journalism across Canada and at this point we only see the situation getting worse,” Honderich said.

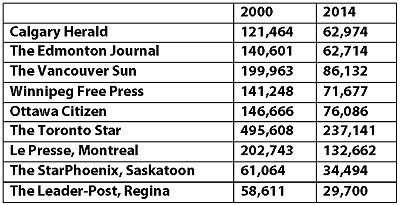

The starkest evidence of what’s happening to newspapers is the decline in paid circulation. The chart below shows a small sampling of what’s happened over 14 years in terms of paid newspaper circulation in Canada. It’s not a pretty sight.

Clearly, the newspaper industry in Canada is in dire straits. But is the public interest being harmed by a decline in good journalism as a result of a failing newspaper business model? The drop in readership of printed newspapers has been offset by the emergence of almost unlimited digital online sources of information, news and opinions.

The core of the issue is not how citizens get their news, but if they have access to the type of credible information they need to be well-informed citizens. That’s the role of journalism, whether print or digital. The policy question this raises goes back to Jefferson’s long-ago observation. Is journalism so fundamental to the proper functioning of a democracy that the viability of the newspaper industry is a public problem in need of a public solution? If so, what form should that take?

Governments have avoided intervening in the daily newspaper sector in the past because they don’t want to be seen as attempting to influence a “free” press for partisan purposes, and there has been no economic need, as privately-owned and publicly traded newspaper companies have traditionally been very profitable. However, if the decline of print journalism holds implications for the wellbeing of our democracy, then the newspaper business is not like just any industry. The need for a well-informed citizenry is the foundation for good governance, specifically the ability to ensure government is held accountable to its public.

There is no obvious metric to judge whether democracy is being debased by the decline in newspaper readership. Voter turnout, which has been declining for decades, is one measure sometimes cited. But attributing reasons for voting behaviour with any precision is not easy. Moreover, we saw turnout increase in the last federal election, one where the Liberal party made excellent use of social media. Indeed, one can argue the sheer volume of news, commentary and information freely available online would suggest people are more informed than ever. But with the Internet often unfiltered by journalism, it frequently becomes a trove of distortions, innuendo and outright falsehoods masquerading as legitimate news. One can reasonably argue that the spectacle of the U.S. presidential election, and particularly Donald Trump’s bizarre and unconscionable campaign, is a manifestation of how public debate has been debased by the spread of half-truths, deception and outright falsehoods.

If the decline of newspapers is a public problem, the question shifts to what form a public policy response should take. What minimal print journalism policy that exists is the responsibility of Heritage Canada. It offers support for newspapers and magazines in the form of the Canada Periodical Fund (CPF) Aid to Publishers component and Business Innovation grants, which provide financial assistance to Canadian print magazines, non-daily newspapers and digital periodicals.

Clearly, government believes there’s a role for public policy to help shape the media landscape. The most obvious examples are the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission. Today, CBC receives more than $1 billion a year from Ottawa to support its English and French, radio and TV operations as part of national cultural policy, with the Trudeau government expanding its support. But in constant dollar terms, CBC funding is significantly below its level of 20 years ago.

If this time is truly different, new policy solutions will be needed. To ensure good journalism doesn’t require government rescuing newspapers. It can strengthen the existing primary policy instrument already in place to provide Canadians with the journalism they need. Specifically, that’s the CBC.

There will be those who will recoil in absolute horror at the thoughts of a strengthened CBC, which they believe is already bloated, wasteful, populated with huge egos, and has an inherent bias reflected not only in programming, but its journalism. Those are not baseless criticisms, but they can be addressed. What needs to happen is for CBC’s mandate to be changed and modernized. It must focus its resources into news and public affairs, in both TV and radio, and withdraw from drama and culture. There is no longer a need for a main CBC network dedicated to Canadian entertainment productions. The government can mandate that programming to be carried on numerous other speciality channels. Instead, the CBC should put its resources into its TV news channel and national radio service.

In a fragmented digital media universe, where people often self-select their news sources and exist in echo chambers of their own views and opinions, there is a public good in the CBC being a stronger journalistic presence, nationally and locally. A truly 24-hour, news and public affairs CBC that expands its coverage of Canada and the world, that diverts resources from its corporate bureaucracy to on-the-ground journalism, local coverage and a more robust online presence, would put the CBC at the forefront of global journalism. At the same time, CBC should no longer be allowed to compete with private broadcasters for advertising dollars. The CBC must become an instrument of journalism that is completely publicly funded and has its journalistic independence not only defended, but externally monitored to ensure all voices and perspectives are being heard in a way that reflects the diversity of the nation.

Admittedly, it won’t change the grim reality future for newspapers. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a public interest in supporting quality journalism to help provide the kind of public oversight that Jefferson long ago identified as critical to democracy.

Dale Eisler is Senior Policy Fellow at the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Regina. He spent 16 years in senior positions with the Government of Canada, including as Assistant Secretary to Cabinet in the Privy Council Office and Consul General for Canada based in Denver, CO. In 2013 he was awarded the federal public service Joan Atkinson Award of excellence. Prior to joining the federal government, Mr. Eisler spent 25 years as a journalist. He is the author of three books.