White knights in film noir

Hildy Johnson, in her pinstripe suit and jaunty hat, enters the office of her editor, Walter Burns. She’s quitting. She won’t be dissuaded by quick-talking Walter, her former lover. She’s through with the dirty business of journalism, wants to settle down and start a family. Walter doesn’t believe her. She’s a journalist, through and through.

“A journalist?” asks Hildy. “Now, what does that mean? Peeking through keyholes, chasing after fire engines, waking people up in the middle of the night to ask them if Hitler’s going to start another war?”

His Girl Friday is an archetypal romantic comedy starring Rosalind Russell and Cary Grant. It follows Walter and Hildy through a tumultuous day of hijinks and nonsense. His Girl Friday is also a classic in another genre— journalism films.

Hildy and Walter make all sorts of morally questionable decisions, including bribing sources, kidnapping an old lady, and harbouring a fugitive. They’ll do anything in pursuit of the scoop. The film could leave the audience with the view that journalists are abominable.

North Americans have a skeptical view of the press. According to a 2016 study by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, only 47 per cent of Canadians and 27 per cent of Americans agree that “you can trust journalists most of the time”.

Most people never personally interact with a journalist. Joe Saltzman, a professor of journalism at the University of Southern California-Annenberg, and founding editor of The Image of Journalists in Popular Culture journal and database, says people get ideas about journalists from popular culture.

“How many people do you know have seen a journalist in action?” asks Saltzman. “They rarely visit a newspaper, a magazine office, broadcast and now internet sources. Most of them don’t even know a journalist. So the question is, how come they have such a very specific idea of what a journalist is, and what he or she does? And my answer is they’ve read about journalists in novels, they’ve seen them in television shows, and they’ve made their assumption of what journalists should be and what journalists are.”

Matthew Ehrlich is a professor of journalism at the University of Illinois, and author of the book Journalism in the Movies. He says this assumption rests in a hyper-reality used to entice audiences.

“It’s sort of a fun house mirror distortion of the way real journalists work,” says Ehrlich. “A lot of what real-world journalists do isn’t super exciting. It doesn’t save people’s lives; it doesn’t destroy people’s lives – the way it does in pop culture.”

The images of journalists the public sees on their screens resonates as they read real-life newspapers and watch real-life news broadcasts. Movies inform our worldview, whether we like it or not.

Toni Luskin, a specialist in media psychology, says movies work through suspension of disbelief. She’s the vice-president and chief operating officer of Luskin International, a media education consulting firm, based outside of Los Angeles. Movies ask the audience to take what’s happening on-screen as reality, she says, and try to reconcile it within their own ideas of how the world works.

“If they go into a film and see something that’s totally foreign to them, it informs them about a certain type of behaviour,” says Luskin. “Then if they go out into the world and see that behaviour, they get in their mind to say, ‘Oh, this is the way it is’.”

When we see stereotypes in film our brains take those patterns of behaviour and reassign them to our perception of the real world. “If we find patterns, we make meaning from patterns,” says Luskin. “And that’s the way we assemble our constructs of reality.”

This skewed worldview may have greater consequences than individual prejudice, Saltzman says, especially in the United States. “The ramifications of how the public perceives and judges the media,” he says, “can have a profound effect on the success or failure of our American democracy.”

In their 2015 book Heroes and Scoundrels, the Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture, Ehrlich and Saltzman investigate the two biggest tropes of movie journalists. Journalists are typically portrayed as either noble truth seekers, who try to expose corruption, or scoop-hungry villains who will do anything for personal gain. “A lot of what pop culture journalists do,” says Ehrlich, “is show the very best of what journalists can accomplish and the very worst journalism can accomplish.”

In some circumstances, villains and heroes are obvious. Villains are typically periphery characters who twist the truth, like Mary Sunshine, the tabloid writer in Chicago. Heroes are people like Woodward and Bernstein in All the President’s Men, who sacrifice sleep and safety to expose wrongdoing.

According to Saltzman, some heroes and villains are more nuanced. If a journalist does things like lie or cheat – but does so for the good of the people – the public usually regards him as a hero.

“If, however, he does the same things so he can win political office,” says Saltzman, “or make a killing on the stock market, or do anything that helps his own self and ignores the public interest, then they’re a villain and the public will not forgive them.”

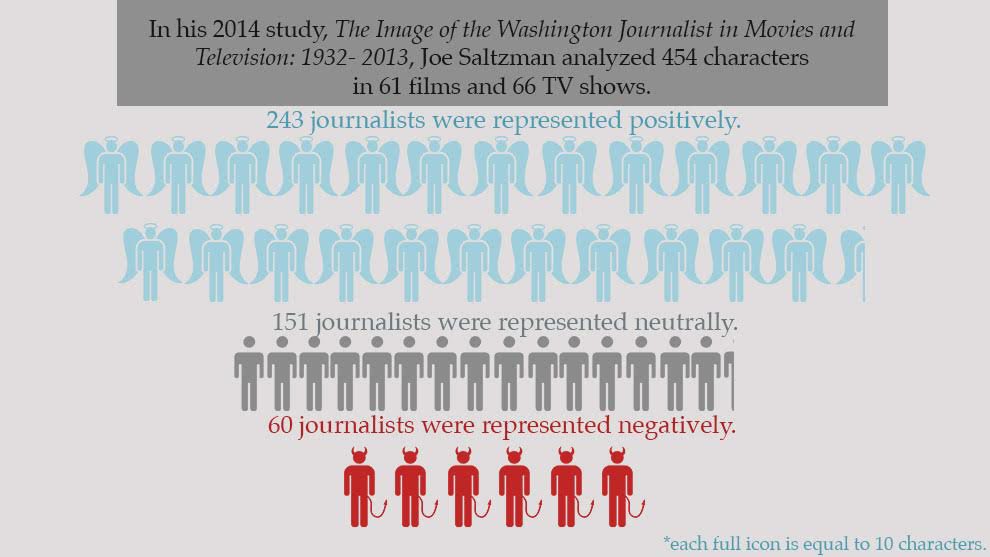

In his 2014 study, The Image of the Washington Journalist in Movies and Television 1932 to 2013,Saltzman found that, in 66 films and 61 television shows, Washington journalists were represented positively most of the time. This is because Washington journalists work for the public interest.

But for every hero, it appears there must also be a villain.

Richard Ness is the author of the 1997 book Headline Hunter to Superman: A Journalism Filmography. A professor of journalism and film studies at Western Illinois University, he is now compiling a “film encyclopedia” that will include more than 1,000 films featuring journalists as significant characters.

“There’s still kind of a love/hate attitude toward the press,” says Ness. “For every movie you get about good, crusading journalists, it seems like one will come out within a year or two that shows the negative side.”

In the 1951 film noir Ace in the Hole, Kirk Douglas plays a reporter for a paper in a sleepy New Mexico town. After many slow news days, Douglas hears about a treasure hunter stuck in a mine shaft, and tries to prolong the rescue efforts to get a better story. He’s a scoundrel.

A year later, Deadline U.S.A. was released. Humphrey Bogart stars as a fearless editor who hopes to expose a gangster – and at the same time keep his paper afloat. He’s a hero.

Ness cites Nightcrawler, a thriller released in 2015. It stars Jake Gyllenhaal as a “sleazy operator” journalist who records, and in some cases creates, violent events to sell the footage to news shows. In contrast Spotlight, released in 2016, is a film about intrepid Boston Globe journalists trying to expose systemic abuse within the Catholic Church.

“There’s never a very long period where journalists are only the bad guys or only the good guys,” says Ness. “It seems like as soon as they swing in one direction, another film will come along and swing in the other direction.”

Jason Anderson, a film critic, short film programmer for the Toronto International Film Festival and a lecturer at Ryerson University, says stereotypical characters are often based on people’s pre-existing assumptions, because that’s an easy way to engage audiences.

“It’s a convenient short cut,” says Anderson. “Everyone knows what this kind of character is like. Or everyone has assumptions about a noble journalist or a not-so-noble journalist character.”

Journalists as characters are an easy narrative device. They are, after all, in search of an exciting story. Journalism movies work well because they are “kind of like detective stories,” says Anderson, “where a detective is going from one person to another and getting them to talk about something.”

Ness, from Western Illinois University, says journalists make for better cinema than detectives because of the fast-paced nature of news.

“It’s a narrative device that gives it a kind of immediacy,” says Ness. “In the 1930s, Warner Bros. used the journalist character a lot, and they even used it in things like horror movies because it made the horror movie seem like it was coming right out of today’s headlines.”

Since the 1930s, 14 journalism movies have been nominated for best picture at the Academy Awards. That’s one every six years. These include Orwell’s Citizen Kane, Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent, and George Clooney’s Good Night, and Good Luck. Last year, Spotlight won.

Fictional journalists, like real journalists, are a part of our culture. It’s up to every viewer to interpret between fact and fiction, between noble journalists and villainous ones.

Hildy and Walter, at the end of His Girl Friday, expose a corrupt sheriff and mayor. They come off as good guys, even though they commit crimes throughout the film.

“Oh Walter, you’re wonderful,” Hildy says in the first scene. “In a loathsome sort of way.”

This story originally appeared in the University of King’s College Signal, and is republished here with the author’s permission.

Michelle Cuthbert is a fourth year journalism student at the University of King's College. She can be reached on Twitter at @michellecuth4.