Linda Kay was the first woman sportswriter for the Chicago Tribune, in the 1980s. She considered herself a pioneer at the time. But years later, when she became a professor in Montreal, she began wondering about the women who came before her.

Kay found an online advertisement for the 100th anniversary of the Canadian Women’s Press Club. “What? What is this? A press club? It’s been around for 100 years?” she asked herself.

After researching, she found out that a female sportswriter in the 1930s worked for the Globe and Mail. “I’m thinking, oh my God! That was 50 years before I became a sportswriter,” she said.

Women journalists have been making a difference in North America for at least 200 years. Stars include, in the late 19th century, American journalist Nellie Bly, who wrote hard-hitting investigative pieces. One of them required her to go undercover as a patient at an asylum. From the 1930s through the ’60s Claire Wallace, a pioneering Canadian journalist, chased daring stories. For instance, she went undercover as a domestic maid to find out how maids were being treated by employers.

Having more women journalists brings new and different perspectives to the media. And while opportunities for American and Canadian women in journalism have improved during the past 50 years, women are still far fewer than 50 per cent of people working in the field, and there still are not many women journalists in top roles.

According to an American Society of News Editors survey, men still dominate journalism in the U.S. This non-profit organization, which promotes principled and fair journalism, released a diversity survey in 2017. Although there are more female than male journalism students, women make up 39.1 per cent of newsroom employees. This means that the news is predominantly covered by men.

A report by the Women’s Media Center shows the consequences of not having enough women reporting the news. The Washington, D.C.-based NGO works to raise awareness about women in the media.

The report, released in 2017, states that in 12 top American news outlets, campus sexual assault and reproductive stories are written mostly by men. The men who covered the sexual assault stories were also more likely to concentrate on the impact of the rape charges on the alleged perpetrator and his behaviour. On the other hand, women journalists who covered sexual assault were more likely to concentrate on the alleged victim’s behaviour and the impact of the rape on her. The study revealed an unconscious change of perspective that occurs when stories are covered by men or women.

Increasing diversity in newsrooms increases the diversity of journalistic perspectives, says Danielle Kilgo, a journalism professor at Indiana University-Bloomington.

Not only do women have different perspectives, but they also emphasize different ideas than men. Informed Opinions, an Ottawa-based NGO that connects women experts with media outlets, conducted an experiment in 2013 on op-eds. It found that only women writing op-eds prominently used words including: abuse, assault, children, equality, cuts, discrimination, education, people, policy, support, treatment, violence, etc.

“Women don’t necessarily do it better,” Kilgo says. “They do it differently. And I think that difference is so important.”

While it is important to have women journalists in newsrooms, U.S. studies show that women are leaving journalism. The Women’s Media Center reported that work by women anchors, field reporters and correspondents in broadcast news fell from 32 per cent in 2015 to 25.2 per cent in 2016. Furthermore, a 2013 report by Indiana University shows that women journalists leave journalism at an earlier age than men.

It is up to newsrooms to make sure that women’s voices are included, says Sandra Fish, the president of the Journalism and Women Symposium, a Michigan-based non-profit that supports the growth of women in journalism. Fish says that journalists lean towards stories that they’re interested in, but need to consider their audience. Women reporters are significantly lacking in beats like sports, politics and business, and so women’s views are not being represented in these areas. (The Women’s Media Center report, meanwhile, shows that women dominate areas such as Health, Education and Lifestyle.)

Linda Kay, now a professor of journalism at Concordia, hopes to see more women gravitating towards areas where they are lacking. Kay, who began her career covering politics and sports, became a lifestyle columnist for the Montreal Gazette and a freelancer for Chatelaine magazine. She encourages her female students who want to go into lifestyle journalism to do it, but to do it like a journalist and not like a PR person.

“I tell my students: business and sports, two areas where you can really make a breakthrough as a female journalist, that’s where women are lacking.”

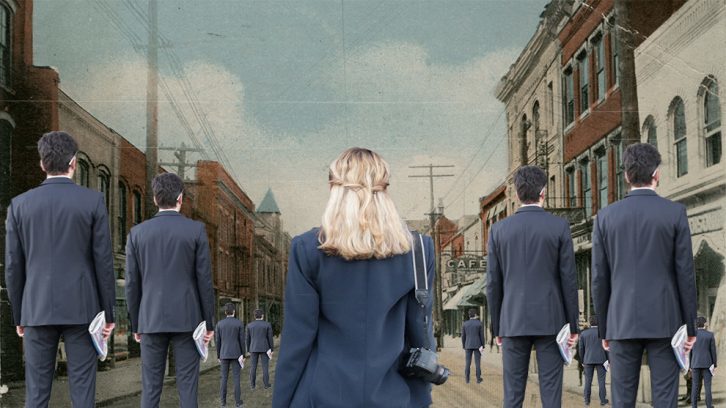

Shira T. Center, who in 2015 became the Boston Globe’s editor of local politics, previously worked in Washington D.C. When she would go to the Speaker’s Lobby where journalists interviewed members of the House of Representatives, she says, “it was filled with suits.”

This meant the Washington press corps was missing something. “The more diversity you have making editorial decisions, the better your coverage is going to be – because it will reflect your readership.”

Canadian perspective

Newsroom gender equality in Canada is better than in the U.S., but still needs work. The International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF), a Washington D.C. non-profit, released a report in 2011 after surveying 11 Canadian news companies. It found that women held 54.8 per cent of junior-level professional positions (writers, producers, sub-editors, correspondents and productions assistants). Women also made up 45.5 per cent of those in senior-level professional (senior writers, anchors, and producers).

The IWMF report showed fewer women in top journalism roles. Women made up 39.4 per cent of the top-level management (publishers, CEOs, CFOs and directors general). This showed that women were hitting a glass ceiling.

Not only was there a gender gap in high-level positions, but a gender pay gap in all work levels. For example, among senior-level professionals women were making 27 percent less than men.

The gender difference is even noticeable for Canadian news and general interest columnists. Dylan C. Robertson, Ottawa correspondent for the Winnipeg Free Press, conducted a 2017 survey for J-Source. The survey found that of 33 national columnists, 42 per cent were women. Out of 90 regional columnists, 37 per cent were women.

Large Canadian news organizations have also shown a gender gap in their newsrooms, according to a 2015 study. The Global Media Monitoring Project studied 23 Canadian news organizations including CTV, CBC, the Globe and Mail, and the Toronto Star. It found that 43 per cent of reporters were women. Additionally, women reporters covering stories on politics and government were 31 per cent. It also found that women journalists were more likely than men to include female sources in their stories.

The Project is self-described as “the world’s longest-running and most extensive research on gender in the news media.” It is run by the Toronto-based World Association for Christian Communication, an NGO that aims to promote communication rights.

American newsrooms suffer from these same issues.

Kathy English, public editor of the Toronto Star, says her paper has encouraged its staff to look for women’s voices when interviewing people. And they look for op-eds by women. “There’s a general sense that women are not represented equally in the news media,” says English.

Women have been doing journalism in North America for at least 200 years. Still, it is promising that some newsrooms have recognized that they need to do a better job of presenting women’s issues.

English says that most of the new hires at the Star are women. Women now make up 45 per cent of the Star newsroom.

“I’d like to think that the concerns of women in society will be given equal play in newsrooms,” English says. “That a women’s world will be presented with some equality to the men’s world.”

This story was originally published on the University of King’s College news site The Signal, and is republished here with the author’s permission.