Student project looks at the stunning fact that 200 years after the first Black settlers came to Nova Scotia, many people still do not have legal title to their land.

By Erin Moore

Journalism isn’t even in the name of my program. It’s called Radio and Television Arts.

But in February, my students at the Nova Scotia Community College, in Dartmouth, launched an investigative journalism project that got picked up by both local and national media and is forcing the provincial government to act.

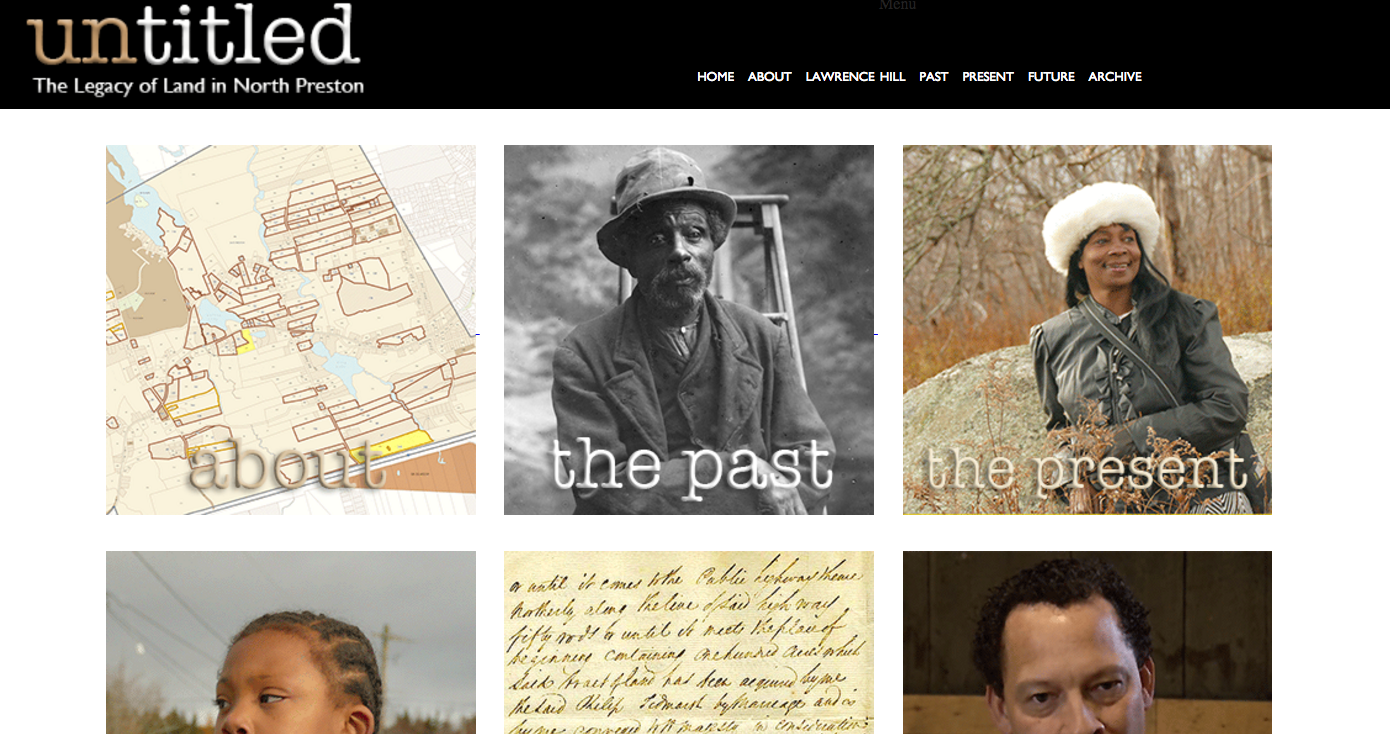

Our investigation is called Untitled: The Legacy of Land in North Preston. It looks at the stunning fact that 200 years after the first Black settlers came to Nova Scotia, many people who live in historically Black communities still do not have legal title to their land.

This means they can’t sell it or legally pass it down to their children. This situation is rooted in racist and discriminatory practices that were employed by the Crown and it has serious social and economic implications.

The issue was brought to our attention in September by the Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society, which had recently started working with people in the community.

It was good timing. Each fall, I teach the generically named “Communications II” course to all 22 second-year students in three specializations: journalism, TV production and radio. It’s become known as “diversity class,” though, because we take a critical look at how some communities are underrepresented or misrepresented by the media.

The issue of land title fit in well—North Preston was settled by people known as the Black Refugees who escaped slavery in the United States after the War of 1812. Today, most of North Preston’s 4,000 residents are descendants of those original settlers. While most Nova Scotians have never visited the community, there is a general perception that it’s crime-ridden and poor, due in part to media coverage.

Instead of reinforcing those ideas, this project would offer historical context about an ongoing injustice. That made me excited to start our investigation but I still had serious concerns. These students only had a year of journalism basics under their belts and half of them weren’t journalism students at all. In a two-year college program, however, these students were about to graduate. It was now or never to tackle a project like this one.

But how would they handle the complexity, scope and investigative requirements of this story? How would I manage a team of 22? How would I evaluate their learning? How would I manage this project and teach four other courses? I didn’t have the answers to these questions until the project was well underway.

The 11 journalism students took the lead with research and interviews, while the TV students were producers, shooters and editors. The radio students took on a variety of roles. Was everyone happy? No. Some wanted better-defined roles and less uncertainty about what the final project would look like. Others just weren’t interested in the story or the work required to tell it. But the story started unfolding in amazing ways, and most of them began to see the value in what they were doing.

In the Nova Scotia Archives, one student found a petition hand-written by North Preston residents in 1841 asking for land title. Here was proof that people had been trying to gain title for more than a century. I think there were a lot of goose bumps when the petition was presented in class that day. I certainly got them.

Our project resulted in a series of five short web videos looking at the past, the present and the future of land title in North Preston. They’re part of a website that also includes photos, an interactive timeline and text.

We also scored an interview with Canadian author Lawrence Hill who has a deep understanding about issues facing Black communities in Nova Scotia and beyond. He agreed to give us an hour of his time when he was in town on a book tour. Hill was generous with the students and let all five who attended the interview take turns asking him questions. In the end, his voice gave a high-profile boost to the project.

Equally powerful was that our class was able to gain the trust of a community that is understandably distrustful of the media. Much of that was thanks to a Dalhousie law student with close ties to the community. She had been working on the land title issue and was keen to help line up interviews and explain on our behalf what our project hoped to accomplish.

When people did agree to be interviewed, we made it a point not to rush them and to spend time listening even when they talked about other concerns. It was important to make this media experience different from what they might have experienced in the past.

Out of respect and appreciation, we aired the project for community members prior to the public launch. We sat in their community centre and watched it, nervously, with them. These were their stories, and we wanted to make sure we got it right. They told us we did.

The students were also forced to confront some of their own stereotypes and misconceptions during this process. To me, that experience alone justified any of the difficulties we had doing the project.

And there were difficulties. There were several times when I wondered what I’d done by letting them take on such a complicated story. Deadlines had to be pushed back repeatedly. I spent many evenings and weekends going out on shoots with my students to offer the in-the-field guidance they needed and deserved. I spent several days over Christmas vetting scripts and trying to visualize where all this was headed. We ended with up far more material than we could use, and the job of narrowing down the essentials fell to me. It was a lot of work, but the story was always worth it.

When the course ended in early December, I gave everyone good marks, regardless of their role. They were all along for the unpredictable ride, and I wanted to acknowledge that.

However, a core group of students worked right up until we launched the project on Feb. 22, during African Nova Scotian Heritage Month (what Black History Month is called in Nova Scotia). They’d long forgotten about marks. It was the passion to tell this story that kept them going. Their passion was rewarded as they watched the story get picked up by media across the province, including CBC, The Coast and The Halifax Examiner, and nationally with a story in The Globe and Mail.

Then, four days after our launch, the Nova Scotia government broke its silence on the issue and promised to right this centuries-old wrong. What an outcome for the students. They saw first hand why journalism matters and that it has the power to make a real difference. And that includes student journalism from a small college program in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia.

Tips for small schools with big ideas:

1. Just try it. Even if the project is big and daunting and doesn’t fit your curriculum.

2. Assign everyone a role, it cuts down on frustration. (I didn’t do this but I will next time!)

3. Get hands on. Go on shoots. Be there in the field for guidance whenever possible.

4. Enlist other faculty to help. I roped in a TV production instructor and a web instructor. And now I owe them lots of beer.

5. Trust your students. They’ll surprise you.

[[{“fid”:”5565″,”view_mode”:”default”,”fields”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:””},”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”attributes”:{“height”:659,”width”:527,”style”:”width: 100px; height: 125px; margin-left: 5px; margin-right: 5px; float: left;”,”class”:”media-element file-default”}}]]Erin Moore is the lone journalism instructor at the Nova Scotia Community College. She was a CBC reporter in Toronto, Halifax and on Prince Edward Island. She has a Master’s in Global Journalism from the University of Örebro in Sweden and volunteered in Ghana for CUSO and Journalists for Human Rights.