By Kate Skelly

Polling has never been more important than throughout the 2016 U.S. election, according to CBC’s poll analyst Éric Grenier.

“Polling does have some caveats. It does have some caution that you have to exercise with it. But it isn’t the bad thing that people make it out to be,” he said. “It’s something that always interested me and it’s something that can engage people.”

But it was another U.S. election that inspired his work. After following the 2008 U.S. presidential election, Grenier founded ThreeHundredEight.com, a website dedicated to political polling in Canada. He strived to recreate the American election forecast website, FiveThirtyEight.com, for Canadians, with his own methodology that has evolved over time.

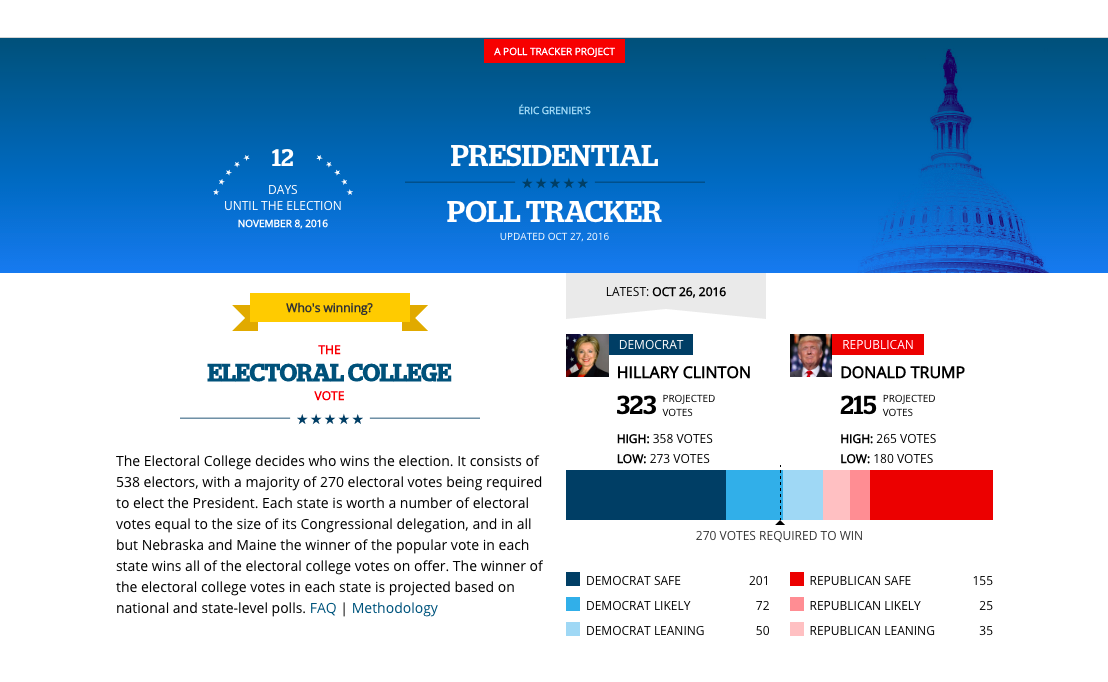

Today, Grenier works on updating the CBC’s Presidential Poll Tracker, following the ups and downs of the U.S. election and counting down the days until Nov. 8, when the next U.S. president will be decided. The poll tracker breaks down the electoral college vote, the state-by-state projections and the national polls average.

His approach involves aggregating polls together, which gives a better indication of where numbers stand at any one poll, and weighs them based on three different factors. The polls that are most recent, have a large sample size and belong to a pollster with a successful track record are the ones Grenier keeps an eye on. Combining these polls together provides the most accurate weighted average, according to his method.

“Often there can be one poll that nails it, but when you look at the margin of error and the fact that there’s just a little bit of chance that goes into it, you don’t know which poll will be the one that will get it really close,” he said.

Every pollster makes different methodological choices and, according to Grenier, paying attention to polls’ trend lines—where the numbers are heading—can be as important as events in a campaign. Analyzing two polls over different time periods can show whether candidates are gaining supporters or falling behind, but only if the polls come from the same pollster. “Comparing apples to apples” is the only way to be sure trend lines are accurate, Grenier said.

Just as media coverage can influence voters’ choices throughout an election, political polling has the ability to get inside people’s heads and sway their decisions, but the effects can steer in both directions. On one hand, people might jump on the bandwagon and vote for the candidate leading the polls. But on the other hand, people might think that their vote is pointless since the candidate is already so far ahead.

“The bigger impact is often in how people perceive the parties and candidates and how the media will cover those candidates,” Grenier said.

According to Grenier, U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump was considered more of a joke than a serious candidate in the Republican primaries, but when media coverage showed him doing well in the polls, he got more attention, which got him more votes. The way the polls have been shooting up and down throughout this election has an influence on how campaigns are being covered and how people view the candidates. Although there is a danger that people can get driven by what is in the polls rather than other factors that should be considered, Grenier said an election without polling would be a mixture of everyone’s opinions with no real evidence backing them up.

Polling has been a part of journalism for decades, tracing all the way back to the early 1800s when newspapers in the U.S. would conduct “straw polls,” printing ballots for readers to fill out and send back to the newspaper, which would make a prediction. Today’s pollsters now face the challenge of low response rates as fewer households have landline phones, and even fewer are answering their landlines and agreeing to respond to a telemarketing-style survey.

According to Grenier, the response rate used to be higher than 30 per cent, but now callers are lucky if they get 10 per cent of people to cooperate. Automated phone calls asking voters to press a certain button in accordance with who they are voting for have dwindled down to a response rate of one to three per cent.

“I don’t think they’ve quite figured out how to adapt with the response rates dropping so greatly,” he said.

Grenier sees a future moving towards a number of different directions. Polls are now trying to reach cellphones, although the difficulty to locate the person and get them to respond may cause some barriers. Pollsters are also conducting online polls, sampling from panels of hundreds of thousands of people, as well as paying more attention to social media and other new means of information. Political polling is working to stay alive by mixing methods and reaching out to people through all different mediums.

Though the terrain is more complex today, Grenier believes the work of pollsters remains as relevant as ever because it “ can help people get more engaged in politics and I think that’s a good thing.”