Why the Toronto Star isn’t fighting a production order issued against them.

By H.G. Watson, Associate Editor

Here are the facts of the case: A reporter interviews a person accused of heinous crimes. A story including parts, but not all, of the interview is published. Several months later, the police serve the reporter with a judicial order, called a production order, for the complete interview. The news outlet fights the production order in court—and loses.

You might think this is a description of the highly publicized Vice Media case against the RCMP. The facts are similar. But it isn’t.

This is a description of a production order brought against the Toronto Star by the Toronto Police Service in the very last days of 2016, a case that has gone completely under the radar.

And, unlike their colleagues at Vice, the Toronto Star has decided it will not continue fighting the production order in court. The differences between the two cases underline how Canadian law fails to protect journalists and their sources.

A tough fight to face

In 2015, Toronto Star investigative reporter Olivia Carville produced a series of stories about sex trafficking in Canada. One of the stories was a wide ranging interview with Matthew Deiaco, a man accused of 19 different crimes, “including human trafficking, assault causing bodily harm, unlawful confinement and kidnapping.”

While Deiaco did not discuss his own case, he told Carville in detail how women are brought into the sex trade. In a video interview, posted on the Star’s website and on YouTube, Deiaco explains to Carville how pimps find “the cracks”—drugs, love—to draw women in.

Carville, a New Zealander who now works at the New Zealand Herald as an investigative reporter, told J-Source in an email she left the Star in December 2015 after she was denied an extension to her working holiday visa. So it fell to Kevin Donovan, the Star’s investigations editor and reporter, to handle the production order when it was issued on Dec. 28, 2016.

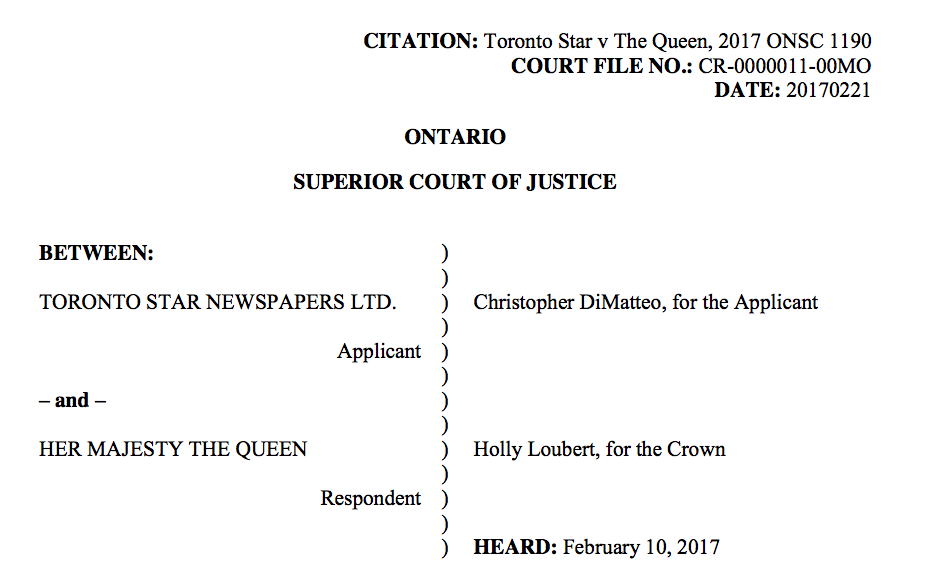

According to the judgment, which is publicly available on CanLii, the production order requested “[a] true copy of all recording(s) in viewable or otherwise accessible and useable form of the interview conducted by Olivia Carville of Matthiew Deiaco at the East Detention Center in the City of Toronto.”

The case was heard on Feb. 10, 2017 at an Ontario Superior Court. Just four days earlier, Vice reporter Ben Makuch stood outside Osgoode Hall at a rally in support of his fight against an RCMP production order for his notes and records of communications with Farah Mohamed Shirdon, a man accused of terrorism. His case has become a rallying cry for Canadian journalists demanding better legal protections, with coverage from every major Canadian news media outlet, including the Toronto Star.

In comparison, there has been no coverage of the Star production order that J-Source could find at press time, including from the Star itself.

Donovan says it would be incorrect to read anything into the Star not covering its own production order battle. “No decision was made not to cover it and in fact I expect we will write about it at some point, particularly as it relates to human trafficking,” he wrote in an email.

The lack of coverage makes some sense when you consider the uphill battle any fight against a production order entails. Even the legal minds at the Star weren’t confident that its own fight would yield success.

“They are much better now at cutting you off when you go in”

According to Nancy Rubin, the president of the Canadian Media Lawyers Association and a partner at Stewart McKelvey in the Maritimes, much of the law around how search warrants and production orders—which deal specifically with documentation—revolved around two Supreme Court cases: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation vs. Lessard and CBC vs. New Brunswick.

In the New Brunswick case, the majority ruled that while the press’ role merits consideration, it does not impose on the police any “new or additional requirements for the issuance of search warrants or production orders”—this, according to what the judge wrote in the judgment issued against the Toronto Star. Some professions, like those that extend privilege to clients, do have additional requirements.

In Lessard, a majority of the Supreme Court dismissed the CBC’s appeal of a search warrant that required it to hand over video tapes of people “occupying and damaging a post office” in Quebec. In the majority decision, the court said that media do get special consideration in cases like these—but they aren’t immune.

They set out nine considerations judges and justices of the peace have to consider when issuing search warrants and production orders. Boiled down to their simplest points, police have to be requesting a search warrant or production order against a media organization if there is no other way to get that evidence, and it has to be a reasonable request that isn’t based on conjecture—it can’t be a “fishing expedition” for evidence, which is what both Vice and the Star have argued their respective production orders were. If those requirements are met, the media organization has to comply.

Rubin says the RCMP specifically has become much smarter about ensuring its production orders meet the Lessard criteria, and it is prepared for the media response. “They are much better now at cutting you off when you go in,” she said.

Star’s case had knocks against it

The Star’s case had some knocks against it. First, no confidential sources were involved. Second, the production order very specifically asked for recorded interviews—not Carville’s notes or other communications with Deiaco. In contrast, the Vice case specifically asked for notes and records of communications between the reporter and subject.

Third, Donovan told J-Source there was nothing in the recording the Star wouldn’t have made public. “In fact, prior to publication, we considered running the entire interview unedited. In the end, we provided edited versions of the video online and in our Star touch tablet edition. We made this decision because our edited versions contained the news,” he said.

Bert Bruser, the Star’s newsroom lawyer, told J-Source that they never thought they had a good chance at winning–but they hoped they could convince a judge they had a good argument. “There is always a chance,” he said.

But he also thinks that judges would not have been sympathetic to them. “If we were protecting a confidential source or confidential information we would be fighting this to the Supreme Court of Canada and beyond, if there was a beyond,” he said. “We didn’t think we would win this case nor did we think it was a good case to change the law.”

As the judge points out in his decision, the video of the Deiaco interview provides “ample evidence here of inculpatory statements by Mr. Deiaco as well as statements relevant to his credibility.”

Iain MacKinnon, Vice Canada and Makuch’s lawyer, said Vice’s case is different from the Star’s. For one, the RCMP has access to other sources of the same type of evidence, and the criminal charges don’t mention anything Shirdon was quoted as saying in Makuch’s stories. (They do mention a Skype interview done with Shane Smith, Vice’s co-founder and CEO, who is based in New York–Makuch is based in Toronto).

“In the case of the Star’s situation, this is a video taped interview where it is clearly the guy talking directly on the same subject that he is being charged with, so I think their facts are tougher for those reasons in particular,” MacKinnon said.

What comes next?

What does this mean for the Vice case, and any subsequent production order cases?

Media organizations and advocacy groups have been very clear that they believe that decisions in favour of production orders have a chilling effect on journalists’ ability to source stories. Both Donovan and Bruser reiterated they were very disappointed by the decision in their cases. Canadian Journalists for Free Expression has spoken out loudly against the decisions in the Vice case.

So far the courts are reading the law as it stands. While judges are required to consider media’s constitutional right to freedom of expression, currently there are no legislated exceptions for journalists.

But the Vice case could potentially lead to a new precedent, suggests MacKinnon. In her dissent to the 1991 Lessard case, Justice Beverley McLachlin wrote that, “given the seriousness of any violation of freedom of the press, the justice of the peace must be satisfied that the special requirements for the issuance of a warrant of search and seizure against a press agency are clearly established and made out with some particularity.”

MacKinnon points out McLachlin is now Chief Justice—and if the Supreme Court grants leave to appeal, she’ll be among the judges to hear the case. The potential outcome, he explained, is that “the Supreme Court of Canada could clarify and expand on the factors and issues that a judge or J.P. must take into account before issuing a production order against a media outlet or journalist.” That could include a more stringent test than what is already in place.

“If they wanted to, they could side more with McLachlin or they could even just provide more details and criteria for judges and justices of the peace need to take into account when issuing a production order in the first place,” said MacKinnon.

However, Rubin is doubtful that judges can read in a new law. “There really isn’t enough room in the code now for judges to make that law,” she said.

She believes that for a court to weigh the balance in favour of the media, there would have to be a very distinct set of facts that show the reporter has a special relationship with the source and the relationship would be imperiled by disclosure. “Then that would in fact affect the ability to gather the news, which is constitutionally protected,” she said. “It’s a hard case to make out.”

That doesn’t mean there isn’t any hope—while judges can’t change the law, legislators can. Bill S-231, the Journalistic Sources Protection Act, was tabled by Senator Claude Carignan in November 2016. If approved, the bill would amend the Canada Evidence Act and the Criminal Code so that journalists would not have to “disclose information or a document that identifies or is likely to identify a journalistic source unless the information or document cannot be obtained by any other reasonable means and the public interest in the administration of justice outweighs the public interest in preserving the confidentiality of the journalistic source.”

It would be a start towards a path for better protection for journalists. Rubin believes that is worthwhile, saying,“I think it would be preferable to have the higher standard built in and mandated.”

2017onsc1190 by jsource2007 on Scribd

H.G. Watson can be reached at hgwatson@j-source.ca or on Twitter.