The long-life of news online means we have to consider a lot when deciding to unpublish a story.

By Krista Simpson

For a column that was only briefly online, Leah McLaren’s retelling of her strange encounter with Conservative leadership candidate Michael Chong’s child has received a great deal of attention. McLaren described her curious, younger self preparing to mimic breastfeeding with the baby after finding him in a bedroom at a dinner party, before Chong walked in. While the piece disappeared from the Globe and Mail’s website shortly after it was posted, it was uncovered in web archives, leading to a flurry of commentary.

In the following days, Chong acknowledged on Twitter that the incident took place but declined to talk about it further. Globe editorial staff did not comment as to why the piece was taken down. McLaren said she cannot discuss it.

While the reasons for this column’s withdrawal remain unclear, it does raise questions about the complicated decision to remove content. Traditionally, unpublishing is something news organizations have been hesitant to do. In recent years, that has changed.

Typically, “the thing that will lead publications to even consider a suggestion of unpublishing will be one of two things: one is a clear legal requirement, and the second is a concern about harm being done,” said Ivor Shapiro, professor at Ryerson University’s School of Journalism and co-author of “How the ‘Right to be Forgotten’ Challenges Journalistic Principles.” Harm, Shapiro explained, usually does not include mere embarrassment. “It will tend to be something more substantial than that.”

But, Shapiro continued, the lines are shifting.

The reason, of course, is the Internet has made the “long tail of news” even longer. Before, finding an old article usually entailed going to a library and searching archives. “Now,” Shapiro explained, “it’s as simple as Googling someone’s name.”

“So that means the long tail of news has become very, very much more every day and life-harming,” Shapiro said.

That has led to members of the public asking news organizations to remove stories that use their name, saying, for instance, that it damages their reputation or job prospects. Shapiro said he can understand many of these requests. “If I had been charged with a pretty bad offence 10 years ago and acquitted, I, too, would want every record of that charge wiped out of existence, because people think smoke is fire.”

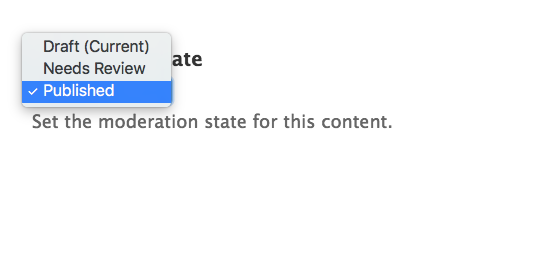

CBC ombudsman Esther Enkin has seen many such requests. She explained that according to CBC policy (which is similar to other news organizations), “the default is that things are corrected if they’re wrong, but the default is to leave it up. But under exceptional circumstances and going through a process of consultation with senior editorial staff, the decision can be made to remove it or alter it in a significant way.”

Enkin explained the “argument about the historical record and not altering it and that being the contract with the reader is a compelling one, but there are also other sides to it.” For instance, “where it becomes a little less clear is especially when it’s youthful indiscretion and it’s 20 years later.” Enkin said that while freedom of expression and the importance of the record need to be considered, so does compassion, and the fact that things do change.

“There is a journalistic notion about minimizing harm, and sometimes it’s difficult to know in this context where that is,” Enkin noted. She concluded newsrooms should have a framework of principles and a process under which situations can be looked at case-by-case. “I do believe it is a slippery slope to easily unpublish. I do believe there has to be a high bar,” Enkin said.

Both Shapiro and Enkin point out there are alternatives to unpublishing, such as updating the story with relevant information or making it more difficult to find in a search engine. Shapiro added headlines and story content are changed often for other reasons, such as optimization or clarification. Those who ask for changes to an article featuring them may be “asking you to do what you would consider anyway for other reasons,” Shapiro said.

This already complicated issue of when to unpublish becomes even more complex when considering other ways journalists now disseminate content, such as Twitter. “I think a lot of journalists are still figuring that out,” said Molly Hayes, a Hamilton Spectator reporter. “If I tweet something and it turns out I’ve made a mistake…or it’s part of a debate and I later change my mind…I think it’s important to leave those kinds of tweets up and recognize and admit when an error is made.”

Still, since original tweets cannot be changed or updated to note a correction, do the same rules apply if an error is caught quickly? Hayes says it may be more confusing to leave those tweets up. She live-tweeted the trial of Dellen Millard and Mark Smich, the men ultimately convicted of murdering Tim Bosma. During active court proceedings, she estimates she tweeted two or three times a minute. “Information was flying really fast,” she said. “Sometimes if a tweet went out, and either there was an autocorrect, or somebody misspoke, I do wonder what is the value of leaving it out there, because people aren’t always going to see the correction.”

When an erroneous tweet is not caught right away, Hayes said it’s important reporters are honest. “I think if you can quote tweet it and make very clear—this was an error, this was an autocorrect, or the lawyer misspoke or I misheard,” she explained. “I think being up front about it is the most important thing.”

She also suggested an extra step may be necessary. “If you can see that three people retweeted it, then I think the reporter has an obligation to reach out to those people and say ‘Hey, by the way, I messed up.’”

Ultimately, Hayes said when using Twitter, taking even a moment to think about what’s being disseminated is worth it. “I think we have to be careful. Sure, you can delete it, but you don’t know what will happen in the meantime.”

Krista Simpson is a videographer and producer at CTV Kitchener, currently on maternity leave. Born and raised in the greater Toronto area, she has a Bachelor of Arts degree from York University and a Masters of Journalism from Ryerson University. She is particularly interested in journalism ethics and the changes facing newsrooms. You can find her on Twitter at @KristaSimpson.