Chelsea Laskowski is a Saskatchewan-based freelance journalist who focuses on northern Saskatchewan and Indigenous people. She has written and worked in radio for The Globe and Mail, Eagle Feather News, Missinipi Broadcasting Corporation, paNOW, News Talk 980 CJME, and Treaty 4 News. She can be found on Twitter at @chelsealaskowsk.

When Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie died on Oct. 17, there was a ripple effect across Canada. Although people had long known his battle with brain cancer was terminal, it was a gut punch to lose a man who constantly forged meaningful connections with complete strangers.

It was only after his passing that I came to realize the similarities between how Downie approached music and how a journalist approaches a story. Songs like 50 Mission Cap and Wheat Kings, and projects like The Secret Path, share true stories of Canadian lives in a near-journalistic way. Delivering someone’s often-personal story to a large number of people is a responsibility that Downie understood, and journalists are tasked with doing the same.

Downie’s family has urged Canadians to harness their grief and create something positive from his death. In that vein, I have found a number of guiding lessons from Downie’s life that can help journalists strive to do what he did so well — to tell human stories.

Do your job with heart. Be passionate.

In a 1996 MuchMusic Egos & Icons profile on the Tragically Hip, Downie explained his passion for creating music as a noise in his head. While touring, he knew it was time for a new record when “the noise starts getting extremely loud … Once you make a record then that volume is turned way down for a few months and you can relax and revel in a job well done.”

Those ebbs and flows are a part of doing something with your whole heart. As a journalist, it’s worth keeping in mind that caring for something deeply sometimes means you take a break so you can do your best when you get back at it. Downie reminds us it is not lazy or selfish to take a breather.

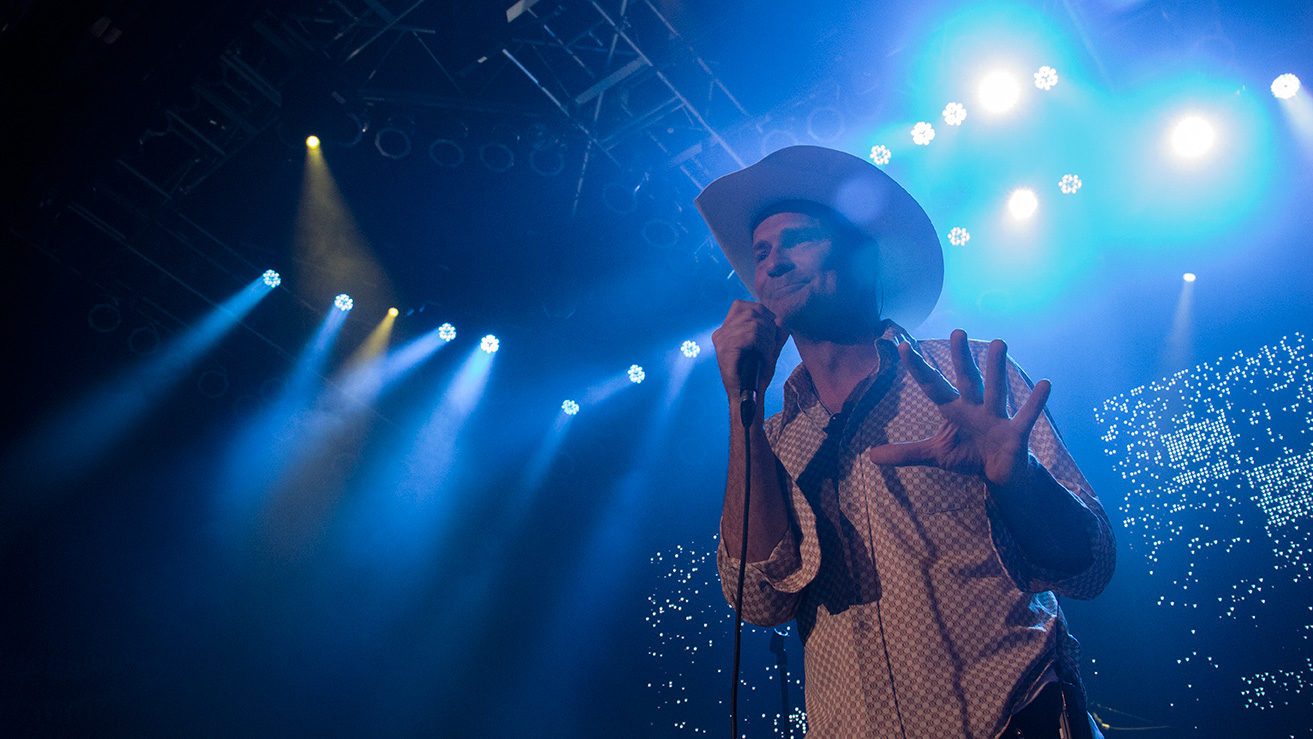

If you want inspiration to see what happens when someone keeps their spark alive throughout their career, look no further than the Hip’s final concert, which was viewed by more than 11 million people.

It’s not all about you

Surprisingly, despite Downie being a Canadian icon who wore bold a sparkly leather suit for his final tour, he was a humble dude. Kevin Drew of Broken Social Scene told the New York Times, “he has an incredible way of giving you that spotlight when he’s in front of you.”

Downie listened intently to people from all walks of life and the songs he wrote were either about other people, or about universally relatable experiences.

As journalists, it’s hard to get past ego sometimes when our faces are constantly on camera, or our names in a byline, or our voices are on the radio — but Downie and the Hip showed the heights people can reach if they focus more on others and less on themselves.

Collaboration makes you stronger

In journalism, a good idea is often held up as sacred. And in return, journalists can become over-protective of our ideas and act like we need to take it all on by ourselves.

The Hip’s songwriting methods are a great reminder that collaboration enriches how we bring our ideas to life. Everyone in the Hip wrote their songs together, and the musical component was treated as a further part of that song’s signature. As lifelong friends, the Hip was able to let the song come first.

“We decided also that a song that we write is not really a song that we write until every guy has put his stamp on it,” Downie said in Egos & Icons.

Show, don’t tell

For decades, people have puzzled over the elusive meaning behind many of the Hip’s lyrics. The band certainly didn’t hit you over the head with their lyrics, instead letting people absorb the meaning of a song for themselves.

In Egos & Icons, Downie said that’s what made his group not particularly good at music videos. “When you actually have to say, ‘Here’s what I look like and this is what I’d like you to think further about the song we’re about to show you,’ then it becomes something that I can’t quite deal with.”

By approaching music in a way that recognized the agency of the audience, the Hip was able to reach a wider audience of people across the country. That is transferable to journalism: good journalism doesn’t tell people what to think or what to do. It guides them on a path and trusts them to come to their own conclusions. As my fellow journalist Tory Gillis tells me, Downie was able to appeal to every kind of community, “and he did it with words and songs that simply reflected us all back.”

When a person, story, or topic keeps nagging at you, there’s probably something there.

The intriguing story of Toronto Maple Leaf’s player Bill Barilko’s 1951 disappearance and the Leaf’s failure to win a Stanley Cup until his body was found lay the foundation for the song 50 Mission Cap.

Downie said Barilko’s story kept popping into his head, and even though he worried it wouldn’t make sense to an American audience, or that no one would care, the Hip eventually wrote a song about it. “Until you record it you’re grappling with ‘Why am I doing this?’” he said in Egos & Icons. Despite that initial hesitation, 50 Mission Cap went on to become one of the Hip’s most popular songs.

As journalists, whether we feel a small instinct to ask that extra question in an interview or whether we find ourselves drawn to cover a certain topic, there is likely a reason for it. I’m not saying we’re going to hit 50 Mission Cap levels of success, but in my experience it is always worth pursuing that topic you just can’t seem to shake.

Be empathetic. Be sympathetic.

In live concert footage from the early 90s, before launching into Wheat Kings, a song about David Milgaard’s wrongful conviction for murder, Downie tells the crowd, “I won’t pretend to understand what it’s like to be in jail for 20 years. I won’t pretend to understand what that feels like nor will I pretend to understand what that feels like, especially if you’re innocent.”

Much of the Hip’s best music was inspired by other people’s stories, which says a lot about their capacity for empathy and sympathy. How closely they understood someone else’s lived experience reminds me of one of my favourite journalists, Louis Theroux. In both, I see people who used their platforms to remind people that they are more alike than they are different. In journalism, interviews and stories are made better when you can relate to someone on a human level.

Find the underreported stories of marginalized people. Tell their stories through a lens of compassion.

Downie’s final passion was fighting for justice for Indigenous people. That was ignited when his brother Mike brought him a 1967 Maclean’s article about Chanie Wenjack, a boy who froze to death after running away from Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario.

Gord spent a significant portion of his dying days writing songs and working to bring to life the graphic novel and video accompaniment for Secret Path, a story about Wenjack. Downie’s family and the Wenjacks also chose to use the publicity of his final tour to create and promote the Gord Downie and Chaney Wenjack Foundation.

As someone who writes stories on Canada’s Indigenous people, I have found inspiration from the compassion and respect he showed for the stories of marginalized people. And I think we can all learn a thing or two from the way Downie carried himself.

Editor’s note, Nov. 24, 2017, 9:54 a.m.: An earlier version of this story incorrectly spelled Tory Gillis’ and Chanie Wenjack’s names. We apologize for the error.