Abdullah Shihipar is the first-ever J-Source/CWA Canada Reporting Fellow. Shihipar has written about the media and social issues for numerous publications, including the Globe and Mail, Quartz, VICE, CANADALAND, Torontoist and NOW Magazine.

Turning on the TV or listening to the radio these days, it seems like the same old voices and perspectives continue to take up space on the airways; you can change the dial, but you’d be hard pressed to find more variety.

Canada’s radio and television landscape is largely dominated by four companies; Bell, Rogers, Corus Entertainment and Quebecor. This can obscure the fact that there are plenty of other players in the game; campus and community radio and TV, as well as media outlets that serve immigrant, Indigenous and other underrepresented communities, that all play a vital role in keeping Canadians informed. Despite their importance, they continue to be shut out in an industry that favors media ownership by large conglomerates.

“All of our main commercial telecommunications companies own all of the main commercial television operators in the country and have significant stakes in the speciality and pay television cable channels,” says Dwayne Winseck, a professor at the School of Journalism at Carleton University.

The government agency that oversees the radio and television industry is the Canadian Radio Telecommunications Commission. Created in 1976, it regulates the industry based on the standards outlined in the Broadcasting Act; among its stated mandate is a commitment to ensure there is “a wide range of programming that reflects Canadian attitudes, opinions, ideas, values, and artistic creativity.” But how well does the CRTC live up to its own mandate?

In order to tackle the issue of corporate monopolies, in 2008 the CRTC introduced the “diversity of voices” policy. This policy made it so that any change in media ownership, through a sale or merger for example, which would result in a company taking a 35 per cent of the total share of the market would be carefully examined by the CRTC. Any change in ownership that resulted in 45 per cent market ownership would be prohibited.

In 2012, a proposed sale of Astral Media to Bell was blocked by CRTC for violating this policy. A year later, the sale was approved after some Astral properties were sold to other companies.

Winseck says the “diversity of voices” policy is quite weak and does not address the issue of vertical integration. Vertical integration refers to the fact that because telecom companies control both the channels and the service that delivers them to you, they can promote their own content at the expense of others. This gives the telecom companies a significant advantage in asserting their monopoly even if controls are placed on how many media properties they can own.

How Canadians can take action

While the present situation may seem abysmal, there soon be an avenue opening up to make significant change, and all Canadians, as Dwayne Winseck points out, can do something about it.

“The telecommunications and broadcasting acts are up to be reviewed within the the next year or so and so Canadians need to pay attention and try to influence those reviews by letting the Minister of Canadian Heritage, Mélanie Joly and the Minister of Innovation, Navdeep Bains, know that they care about these things,” he said.

“The telecommunications and broadcasting acts are up to be reviewed within the the next year or so and so Canadians need to pay attention and try to influence those reviews by letting the Minister of Canadian Heritage, Mélanie Joly and the Minister of Innovation, Navdeep Bains, know that they care about these things,” he said.

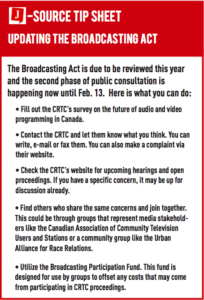

The CRTC is currently in the second phase of its public consultation on the broadcasting act and is inviting Canadians to give their input via a survey up on its website until Jan. 31.

“The CRTC must submit a report on future distribution models for Canadian programming, including both audio and video programming, as well as its continued creation, production and distribution and has launched the survey to better understand why Canadians are consuming content the way they do,” the commission said in a statement.

While the consultation period may be coming to an end later this month, people can still provide input at any time. If you have a specific issue, you contact the CRTC and file a complaint. These forms can be found at the CRTC website, along with a list of upcoming hearings and open proceedings.

Navigating the bureaucracy of the CRTC may be a daunting task for one individual to take on, which is why many stakeholders come together and present as groups to the CRTC.

In an attempt to level the playing field between larger corporations and smaller stakeholders, the CRTC, through the Broadcasting Participation Fund, provides funds for these groups to conduct research, hire consultants and put together reports for proceedings — but they are often speaking from the sidelines, not centre field

The industry players

Who exactly are these smaller groups and how does the CRTC usually interact with them? Not much, said Barry Rooke, who serves as executive director of the National Campus and Community Radio Association. He said contact with the CRTC only occurs when there is an annual review of licenses or a turnaround in staff, or if a problem pops up.

“There appears to be very little awareness of our sector; what we are doing, how many people are listening and so on,” said Rooke.

Campus and community radio stations are usually small operations that rely mostly on volunteers to run programs and keep the station running. As a result of the CRTC’s lack of awareness, Rooke said, regulations are not designed with community stations in mind.

“A good example of this is an average broadcast week is 126 hours, campus community stations are required to fill 15 per cent of the broadcast week of programming that is spoken word. If you have five (to)15 volunteers, how are you as one of those five volunteers going to do your part to speak for four hours on the air every week?” he said.

According to Rooke, the new CRTC chair, Ian Scott, who joined the organization this year, has expressed a willingness to hear from smaller groups that get drowned out by the larger telecom companies. So far, Rooke said, there has not been any real effort to make contact on the part of the CRTC.

Community television stations have also expressed frustration with the CRTC. These stations can be grouped into three categories: those which have their own licenses, those of which are owned and operated by cable companies, and then there are community TV corporations. These stations are owned by cable companies, but the content that airs on it is produced by not-for-profit organizations.

Cathy Edwards, executive director of the Canadian Association of Community Television Users and Stations points out that when the CRTC created the license class for community stations in 2001, there was no funding attached to it. As such, very few community TV stations were established as standalone licensed stations.

Cable companies are required by the CRTC to provide for a community channel. Years ago, companies were more open to having citizen involvement and locally produced content. However, as fewer people subscribe to cable, cable companies are closing studios and centralizing production making it difficult for local, citizen produced content to make it on the air.

Edwards cites New Brunswick as an example, pointing out that they have dropped from having 30 cable production studios to having nine today, and even then it is rare that those studios produce unique local content. In 2010, at the behest of CACTUS, the CRTC did order cable companies to make sure that 50 per cent of content on community channels are citizen produced. But, as Edwards points out, this rule has not been enforced nor have stations been monitored for compliance.

Diversity and representation

Community TV advocates are not the only ones who have pushed the CRTC to hold cable companies accountable. Groups representing people of colour and immigrant communities have lobbied the CRTC to ensure that multilingual programming remains on the air.

In 2015, when Rogers announced that they would no longer produce multilingual news broadcasts for their OMNI stations, groups like the Urban Alliance for Race Relations wrote to the CRTC repeatedly to express their concerns and called upon the CRTC to suspend consideration of further applications from Rogers until the issue was resolved. They also demanded that the CRTC hold a public hearing on the matter. Among their demands was a full restoration of the OMNI multilingual newscasts, in house production of said newscasts, and that the programs receive equivalent funding to that of other programming at Rogers.

The CRTC ultimately ruled against the UARR in early 2016 and declined to hold a public hearing. Then, earlier this year, it was announced that the OMNI newscasts in Italian, Mandarin, Cantonese and Punjabi would return to the air, thanks to a CRTC decision to grant mandatory distribution to a new national service called OMNI Regional. Rogers was granted a subscriber fee of 12 cents per user, per month, which amounts to $15 million. While a step in the right direction, this arrangement leaves much to be desired according to Malika Mendez, vice-president of the Urban Alliance on Race Relations.

Mendez points out that a condition of Rogers’ license is to produce half-hour news segments in four languages, including Cantonese. However, Rogers has contracted out production of its Cantonese news broadcasts to Fairchild TV, an existing Cantonese language broadcaster, thereby reducing the variety of viewpoints available to Cantonese speakers. However, as Mendez explains, the issue goes beyond just Rogers’ and its programming.

“The CRTC needs to strongly support independent broadcasters who offer services to Canadians in languages other than English and French and needs to be more forceful in ensuring that third language services receive mandatory distribution,” she said.

Some of these independent broadcasters serve Indigenous communities, like the Aboriginal People’s Television Network. APTN CEO Jean La Rose said the network’s relationship with the CRTC has been good over the years and he credits it with helping to create APTN in the first place by encouraging the network to apply for mandatory distribution, which brings with it a subscriber fee. Without that fee, La Rose said, it would be hard for APTN to operate the way it does today. That said, there have been some issues.

According to La Rose, while APTN has mandatory distribution, cable and satellite providers are free to place the channel anywhere on the dial. This usually means the channel is assigned an obscure number past 100, and thus gets lost for those customers who order basic cable packages, for example. The channel is still available but customers may have to surf through channel after channel of TV noise to discover it exists. APTN has asked the CRTC to tackle this issue but to no avail.

“In the last three renewals, we’ve asked that the commission direct the distributors to either place us in one specific spot or stop moving us all over the map so our audience can find us on a regular basis and in that area, the commission has been reluctant to go in that direction,” said La Rose.

It’s clear there is a whole set of issues with the CRTC that need to be dealt with; with a common theme being that the needs of large telecom companies are prioritized often at the expense of other smaller stakeholders. While the steady erosion of broadcasting diversity may seem relentless and unstoppable, opportunities like the Broadcasting Act consultations offer one avenue for audience members and community media producers to offer a different vision.