Magda Konieczna is associate professor of journalism at Concordia University in Montreal. Her work focuses on the connections between journalism and democracy through examinations of new business models for news, the growth of collaborative news production, and a community-centered approach to journalism. She is the author of Journalism Without Profit: Making News When the Market Fails (Oxford University Press, 2018) and was a city hall reporter at the now-closed Guelph Mercury.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

When many of my former colleagues at the Guelph Mercury were laid off in 2009, I got in touch to see whether they were going to start their own news website.

This has become increasingly common in the United States. Joel Kramer started MinnPost to fill the gap left in local news after the papers in Minneapolis-St. Paul cut 100 reporting jobs in 2007. After the investigative desk at the Wisconsin State Journal closed, Andy Hall left the paper and started the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

The Canadian government recently announced initiatives to support local journalism, including a measure to classify nonprofit news organizations as charities, making it easier for them to attract donations.

There are a handful of news nonprofits in Canada. La Presse was converted to one earlier this year. The Tyee is one of the stalwarts, along with The Walrus, whose own origin story is a case study in how the government can stand in the way of nonprofit journalism.

The field of nonprofit news is much stronger in the U.S., and I explore it in detail in my new book, Journalism Without Profit: Making News When the Market Fails. The Institute for Nonprofit News is nearly a decade old and has 180 members. Perhaps more importantly, the news nonprofits work together, learn from one another and celebrate each other’s successes, which increasingly include mainstream recognition such as Pulitzer Prizes.

ProPublica Wins Third Pulitzer Prize for ‘An Unbelievable Story of Rape’ https://t.co/5sbOqv2h0h

— Global Investigative Journalism Network (@gijn) April 18, 2016

All this means Canadians have a lot to learn from the U.S. about nonprofit news. So let’s examine how these organizations work, an exploration that will point out that simply making it easier to start a news nonprofit is not quite enough.

Nonprofit news in the U.S.

The impetus behind my book project was to figure out what makes these organizations work. After all, even after rounds of layoffs, the Wisconsin State Journal, for instance, remains a large and well-known entity compared to the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism. So what, I wondered, can WCIJ do that the State Journal can’t?

What I found by embedding myself with these reporters is that sharing and collaboration are key to their success. When two Wisconsin Supreme Court justices got into a physical altercation, the Wisconsin Center partnered with Wisconsin Public Radio to get out the first and most detailed account.

But, despite being first, the Wisconsin Center didn’t keep its scoop for itself. Instead, like it always does, it offered this story to news organizations around the country, for free. As a result, the story was published or referenced 172 times by prominent national organizations such as CBS and NBC, and important regional newspapers like The Appleton Post-Crescent and The Janesville Gazette.

If you live in Wisconsin, you probably haven’t heard of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism. But you’ve likely seen its stories through one of these other outlets.

This is what founder Andy Hall envisioned when he set up the Wisconsin Center.

Hall told me: “It made far more sense to make our stories available to the very sizeable audience that had been developed by public broadcasting as well as all the other news organizations in Wisconsin.”

Focused on sharing

Because they’re funded by foundations concerned about democracy, many of the news nonprofits don’t feel it makes sense to zealously guard their work.

Instead, they see themselves as sharing a common goal of informing the public. They give their stories away so they can attain broader resonance. This sharing is what allows many of them to hit the ground running rather than consigning themselves to years of obscurity while trying to develop their own audiences.

They also protect a key feature of journalism: the way it brings us together to discuss important issues in our communities. The news industry has experienced dramatic fragmentation, especially in the United States. When citizens get their news from totally different places, our realities can start to diverge, as we see south of the border.

By getting their stories into The Janesville Gazette, reporters at the Wisconsin Center are improving the quality of news where readers already are. In other words, they’re not redirecting an elite audience to another news source. Instead, they’re in a sense defragmenting the news industry and increasing the likelihood that citizens have access to a shared reality.

As Canadian journalists start to experiment with nonprofit structures, they’ll need to keep this in mind. If news innovation is a way of further fragmenting audiences, it does democracy a tremendous disservice.

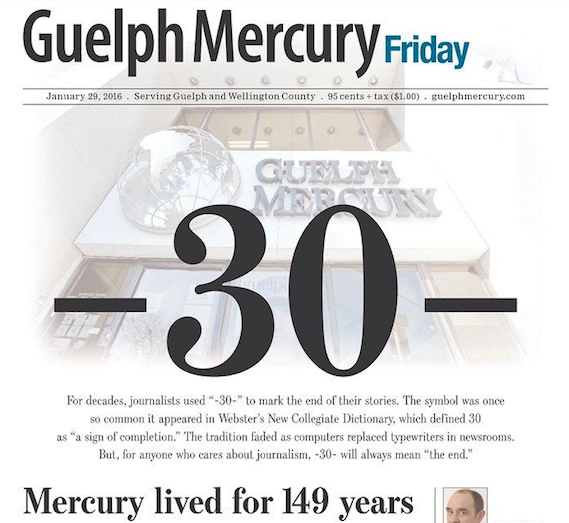

Mercury closed in 2016

Back in Guelph, none of my colleagues started a news nonprofit to cover the city. Instead, my former boss sent me an email after the layoffs, noting: “We’ll keep punching here. But with a lot less weight.”

That was only true for a few more years. In 2016, the Mercury closed after more than 160 years.

The next month, Village Media started Guelph Today. The site publishes news about local events and issues, but it remains a far cry from the regular, daily, in-depth reporting the Mercury used to do, and indeed that we know communities need to function well.

Perhaps a news nonprofit would help.![]()