This series was funded by readers like you through donations to the J-Source Patreon and FutureFunder at Carleton University.

In the summer of 2018, Angela Long embarked on a 22,000-kilometre journey, traversing eight provinces and a territory – from Dawson City, Yukon, to Cape Breton, N.S. – to learn from residents, reporters and experts about journalism’s importance in rural markets. In this series, she tells the stories of local news survivors and the roles they play in bolstering their communities.

When lost on the backroads of southern Manitoba, a sign can make all the difference. Deloraine: A town that loves company. A vista of grain silos, sloughs filled with waterfowl and fields of wheat dotted with oil pumps slowly bobbing up and down shifts to a town filled with baskets cascading with fuchsia-coloured petunias and a more than five-storey-high purple martin tower surveying the railroad tracks. The sound of summer birdsong rises above the rumble of a tractor idling in the parking lot.

At first the scene at the Rendezvous Restaurant doesn’t seem to live up to the town’s promise. It’s the kind of place, like many places in rural Canada, where a lone woman traveller tends to stick out. Families dressed in plaid shirts, jeans and ball caps turn to stare. But a smiling waitress with cropped hair and a pierced nose changes all that. She recommends the quesadillas. And the local paper. “Of course” she reads it, she says. “You can get it next door, at the Co-op.”

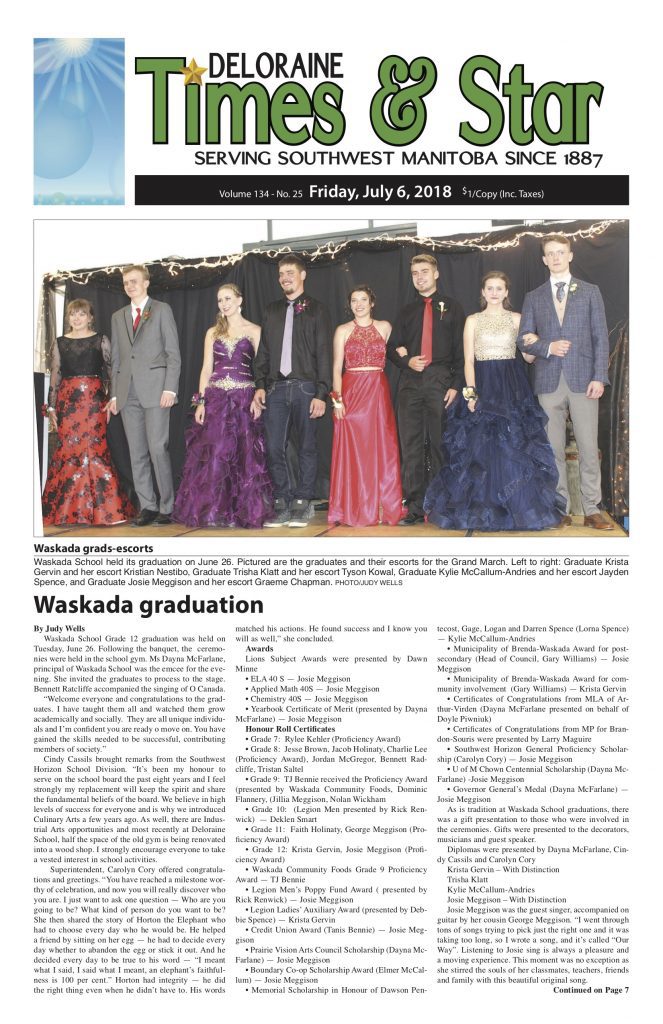

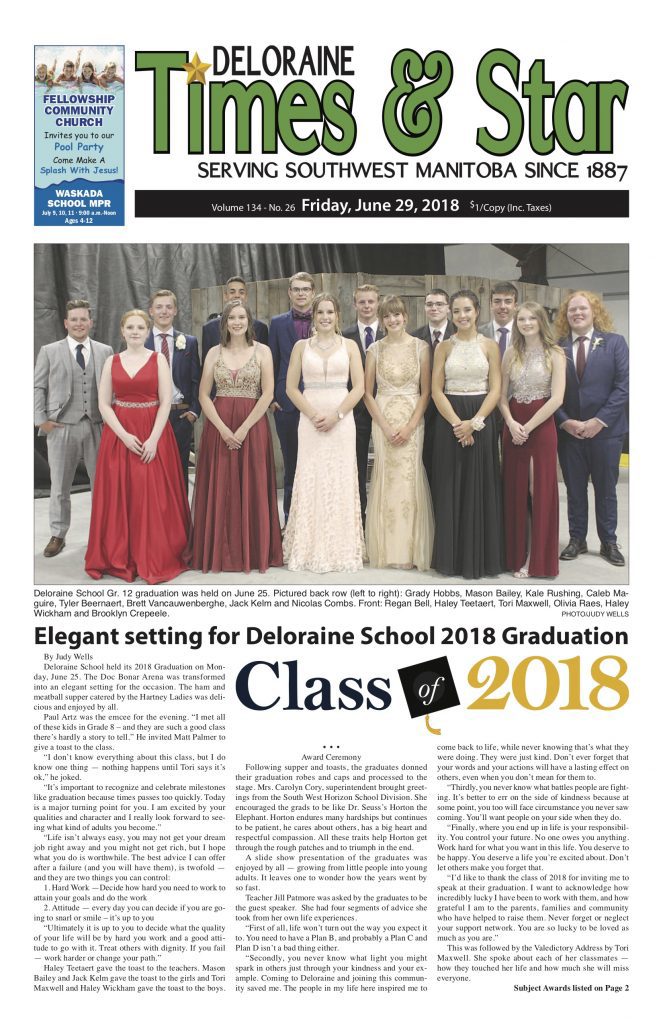

The Deloraine Times & Star is sold out in this town of fewer than 1,000. “It’s the grad issue,” the cashier at the Boundary Co-op Food Store explains, pointing to an office across the street on Broadway Avenue. There a woman in black-and-white polka dots sits in front of a computer while Sweet Child of Mine plays on the radio.

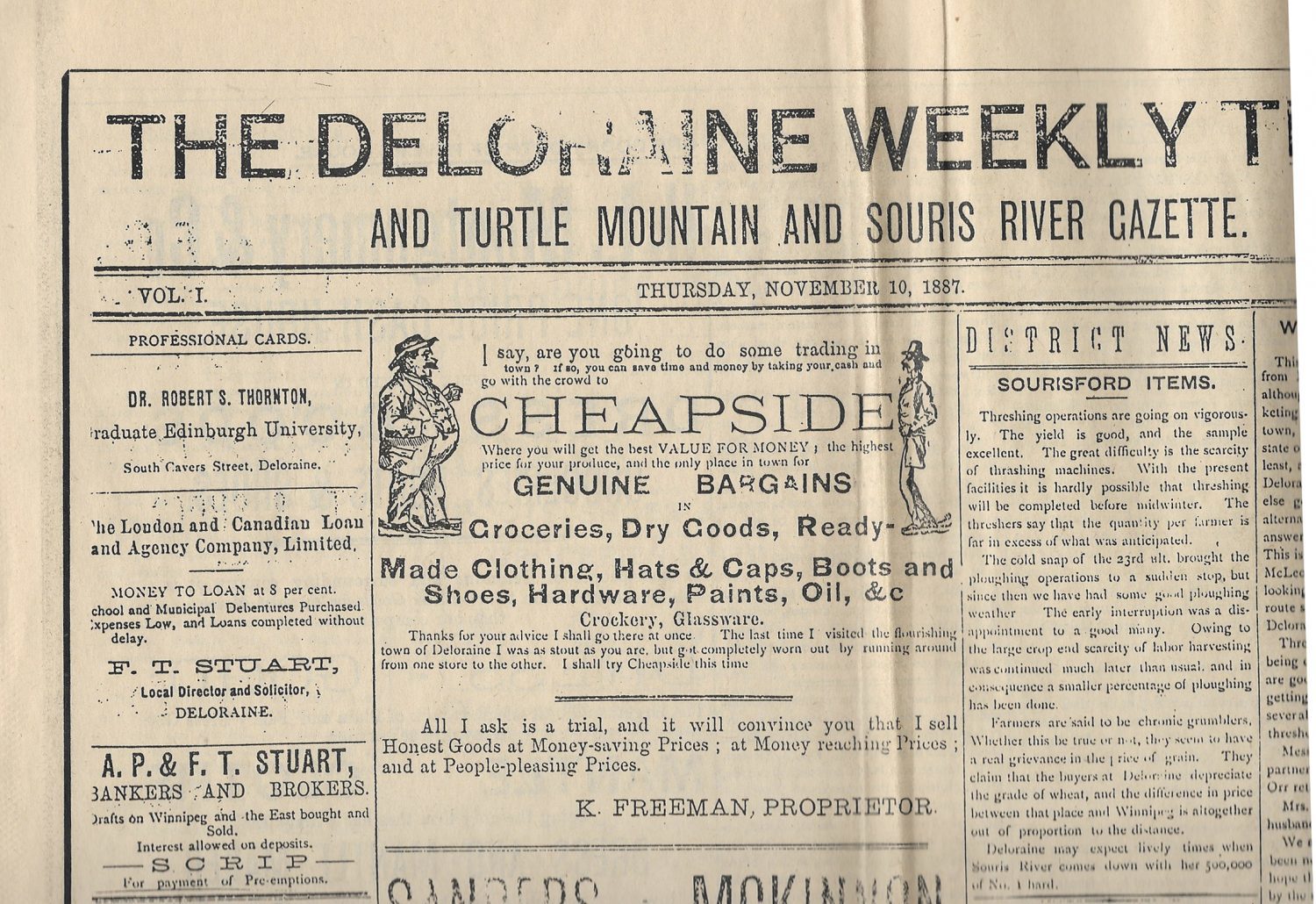

The journalist from Toronto isn’t the only lone woman around here. Fifty-nine-year old Judy Wells, who has spent nearly three decades working in the newspaper industry, is the only employee left at the weekly Deloraine Times & Star. But after 14 years of cuts where the paper’s staff was reduced to one from six, the number of pages was cut to eight from 16, and the original “humongous” office next door was transformed into a tanning salon, Wells is still smiling. The one-woman show at the Glacier Media-owned paper is determined to keep her town’s more than 130-year-old newspaper alive.

Wells has worked at the paper since 1999, five years before it was sold to Bruce Schwanke of Corner Pocket Publishing Ltd. and 11 years before being taken over by Glacier Media – the Vancouver-based company that owns eight of Manitoba’s 54 community newspaper titles – and at the Melita New Era for seven years prior. She doesn’t mind the extra hours she works, hours she doesn’t even bother to count anymore as the reporter, manager and salesperson (responsible for everything but making ads, she says). “That’s my choice,” she says of things like taking 200 photos instead of 20 and staying three hours instead of one just to get the right shot at an event. “I want to see it done right,” she says. “To keep the paper going. It’s important to me, so I just do it.”

Journalists across the country continue to “just do it” despite increased demands caused by a decade of layoffs and buyouts in the media industry, what data journalist and consultant Chad Skelton called “a fact of life” in a 2018 blog post. Various figures, from Statistics Canada, to the Canadian Media Guild, to newspaper employee union chapters such as Unifor Local 2000, suggest cuts range from as low as seven per cent to more than 30 per cent, according to Skelton. The 2017 Public Policy Forum report The Shattered Mirror: News, Democracy and Trust in the Digital Age says 12,000 positions have been lost across the country.

The increased workload isn’t always doable for small-town papers with newsrooms that aren’t very large to begin with. Laura Button, former editor of the 96-year-old Mountaineer – a family-owned newspaper in Rocky Mountain House, Alta. – resigned in late July 2018.

Posters that read “Libraries are radical” and “Say it in a letter, we’re in this together” decorate her office walls. From having a roster of four full-time reporters when she accepted the position in 2014 – five during the summer months – her staff has been reduced, year by year, to one part-timer, a couple of freelancers and, she says, “yours truly.”

She loves being a journalist, Button says in the summer of 2018. In 2008 she graduated from the University of King’s College then worked for papers throughout Newfoundland and Labrador as a reporter, editor and proofreader. But her love for the profession is starting to be overtaken by a desire to “save her sanity,” she says, laughing. With all of the weekend and evening events she covered, Button’s work week could sometimes grow to 80 hours. Twice she counted working 29 days in a row, one time 32.

It’s been eight months since Button made the “gut wrenching” decision to leave the Mountaineer and begin her “second life,” as she describes it in a March 2019 telephone interview. As the communications co-ordinator with the Town of Rocky Mountain House, she can tuck her children in every night, she says. But in such a small town, her former life as a journalist is never very far away.

“For months after I couldn’t go near the building,” she says of her former workplace. “I’d get heart palpitations.”

Although Button once thought being a journalist was something she’d be “until the day I died,” she says, the workload wasn’t “sustainable.” She wasn’t doing her best quality work. She simply didn’t have time.

For the 2015 book Outsiders Still: Why Women Journalists Love – and Leave – Their Newspaper Careers, Vivian Smith interviewed two dozen women in the newspaper industry who were “loving their jobs even as they think about moving on,” as reported in a 2015 J-Source review. Since the 1970s, women have come to consistently outnumber men in Canada’s journalism schools, yet women hold disproportionately fewer of the top positions in the newspaper industry. Carleton granted its first three Bachelor of Journalism degrees to women in the fall of 1946. Yet 72 years later, at a 2018 conference hosted by the Ryerson Review of Journalism in Toronto, panellists still asked: “Is Journalism Failing Women?” and explored ongoing issues such as the industry’s pervasive structural problems and barriers to entry, noting that female readers also notice something is amiss, expressing concern in a 2017 survey that “media is dominated by straight, white, cisgender men, especially in leadership positions.”

The Deloraine Times & Star’s owner, Glacier Media, is no exception. While the province’s regional publisher is a woman and more than 75 per cent of the newsroom staff at the company’s Manitoba community papers is comprised of women, 100 per cent of the company’s executive leadership (six positions) and board of directors (six positions) are men. Seventy per cent of the company’s divisional leadership (10 positions) are also men. The company could be a case study for Linda Steiner, a University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism professor whose 2017 article Gender and Journalism notes a concentration of women in “low-status media outlets and beats” dominating small-town news organizations. Despite a willingness to hire women reporters, “news organizations have resisted women as top executives,” Steiner concludes. A global report published in 2018 by the International Women’s Media Foundation noted glass ceilings in 20 of 59 nations, with women holding 27 per cent of all top management positions.

But gender dynamics don’t concern Judy Wells at the moment. She needs to add the Co-op to her list of things to do. “I’d better get them some more copies of that grad issue,” she says. “Thanks for letting me know.” She shows off the front page splashed with a colour photo of four male-female couples – “the graduates and their escorts” – at the Grand March.

Wells doesn’t really care whether her bosses at Glacier, who she says treat her well and make her feel appreciated, are men or women. Wells has a mission. She has a battle on her hands.

“I fight against indifference, that’s what I do,” she says. “Indifference is what kills a community.” And Wells loves her community too much to let it become one those hollowed-out towns along the backroads of the prairies.

“I think the paper is the heartbeat still,” she says. “I do.”

It’s a heartbeat that has become increasingly difficult to sustain. Wells has been told that in order to keep the print version, she needs to up her ante online. “I don’t know how it works,” she says of online content and advertising on the paper’s Facebook page (which has 276 followers as of April 2019) and through their website. ”We need to get more hits, or clicks, or whatever you call it,” she says. Glacier told her it’s losing money. “They’re just being honest,” she says, but at first the pressure to post content every day was “intimidating and overwhelming.” Even though she’s better able to cope now, “Just finding the time is hard,” she says.

As the one-woman newsroom in an area with a long list of sporting events, festivals, and fundraisers, such as Deloraine Royals baseball games, the Deloraine Agricultural Fair, the Cruisin’ for Cash Motorcycle and Car Rally, and ongoing issues such as flooding and the recruitment of essential medical staff, finding time isn’t easy. Wells used to enjoy sharing the load with colleagues, she says, as well as the camaraderie and ability to bounce ideas off each other. Now she goes next door to Franz Hoeppner Wiens Law Office when she needs advice. “I ask the lawyers what photos they like best,” she says, noting they’ve got a good eye for a front page.

Keeping the print version alive is important to Wells, especially because of the high ratio of seniors in the community who still prefer to hold the paper in their hands. A study conducted by the American Press Institute shows that adults 65 and older who pay for news are five times more likely to buy print than digital. The numbers are similar in Canada. According to a 2017 Media Technology Monitor report, 43 per cent of Canadians over 71 have a print newspaper subscription. A 2016 Statistics Canada report noted that 81 per cent of Canadians 55 and older are more likely to follow current affairs daily, as compared to 37 per cent of their younger cohorts aged 15 to 34. And the number of seniors who want their news is only increasing.

According to Statistics Canada, 5.9 million seniors aged 65 and over lived in Canada in 2016 – 16.9 per cent of the total population. By 2031, these numbers are projected to rise to 9.6 million – 23 per cent of the population. Rural populations traditionally have a higher ratio of seniors than urban areas. In Deloraine more than 30 per cent of the population is 65 and over.

Seniors set the tone for Wells’s vision of an ideal community, where people are engaged and invested in their town, where the battle against indifference can be won. She calls this generation of newspaper readers the “great generation” – people who know how to survive wars and Depressions and help one another.

“They’ve built the community,” she says, “They’ve worked hard for their town. Maybe it’s all they have.”

Wells tells the story of a 90-year old woman who recently came into the office to place a thank-you ad for her 90th birthday party. It’s very important for this generation to thank people, she says, and to do so right away. “That’s how they roll.”

The paper is where they roll when they’re looking for connection, to find out what’s happening in town, to keep loneliness at bay, says Wells. It’s where they learn of the town’s numerous “teas” – social events hosted by groups such as the Legion Ladies Auxiliary, or “fowl suppers” – fundraisers which serve turkey, ham, meatballs. “I think that’s a prairie thing,” says Wells. “Seniors need to know ‘What am I going to do this Tuesday afternoon?'”

A subscription to the Deloraine Times & Star is so essential that “They get the paper until they can’t see anymore,” Wells says.

After more than an hour of talking, a customer walks in the door, looking for one of the sold-out grad issues. She practically snatches the paper out of Well’s hands, scanning for a photo of her son. “Oh, you wrote an article, too?” she says. “I’m going to cry.”

It’s time to cover the kids’ swimming lessons at the local pool, says Wells, then maybe go for a swim herself on this hot July day laced with the scent of flowering canola.

“I think if this starts feeling like a job or something, then it will be time to get out,” she says. “After all these years it still doesn’t feel that way.”

Wells locks the door, directing the journalist from Toronto to the municipal campground, back by the ball diamond, where one soon learns that Deloraine’s mosquitoes also love company. Here a grey-haired insurance adjuster named Jim makes his rounds of the all but two empty sites in a pair of plaid bedroom slippers. “You need more smoke,” he says of the campfire. “You need a smudge.”

Jim looks toward the yellow glow of canola fields bordering Highway 21, reeling off the names of local papers throughout Manitoba like the names of old friends: The Roblin Review, The Exponent, The Dauphin Herald. “More?” he asks.