I’m standing with my hip braced against a camera tripod, keeping it upright as heavy gusts of wind threaten to topple it over. I’m not paying attention to the blizzard swirling around us however — I’m on frostbite watch for the woman operating the camera, keeping an eye on her exposed fingers and hands as she handles the camera, ready to yell at her to get back in the truck if they start to go too white.

Welcome to Rankin Inlet, Nunavut, in January, and journalistic collaboration.

What brought me — an editor from Up Here magazine — and Charlotte Morritt-Jacobs, my friend with the camera and a reporter with Aboriginal Peoples Television Network, to the side of a road in an Arctic blizzard with temperatures dropping to -60 can be blamed squarely on Toronto Star investigative reporter Robert Cribb.

Both of us had been selected to take part in an investigative journalism intensive program at the Banff Centre, and listening to Cribb talk about collaborations between outlets — in his case the Toronto Star and CBC — started discussions about whether sharing between outlets, instead of competing, may be the future of journalism.

Newsrooms are shrinking. Costs are being slashed, especially for things like travel that aren’t seen as necessary. In the south, this is a problem: in northern and remote regions of Canada, however, it’s literally leaving huge regions out in the cold. News deserts are expanding, and in the North, that means voices and stories simply aren’t being heard.

And when they are, they’re often being heard without context, without understanding. Look no further than the New York Time’s fall coverage of Cape Dorset, which starts with the headline Drawn from Poverty: Art Was Supposed to Save Canada’s Inuit. It Hasn’t. It doesn’t get better from there. Written by the Times’ Canada bureau chief Catherine Porter, it’s been roundly panned by Nunavummiut as well as the Native American Journalists Association.

Porter actually did visit Cape Dorset, several times, but her reporting was still parachute journalism at its finest. What she reported wasn’t factually incorrect, but her understanding of what she’d covered was lacking. She saw, but she didn’t comprehend. From understanding the cadence Inuktut speakers have in English to the realities of the culture and living in the North, she missed the point and presented a simplistic and downright colonial version of the Canadian Arctic to the world. Working with other journalists — especially northern and Indigenous reporters — could have changed that.

In April 2019, Nunavut turned 20. That’s a major milestone for Canada’s youngest territory, and both Charlotte and I wanted to offer in-depth coverage of what’s next for the generation of Nunavummiut who have only known the territory as its own independent entity.

Nunavut is unlike anywhere else in Canada. But the cost to even get to Iqaluit, let alone the communities, is high. A ticket from Ottawa to Iqaluit will range between $2,000 and $3,000. To get to more remote regions, like Pangnirtung, will cost even more — over $4,000 from Ottawa, and often over $5,000 from Yellowknife. That’s for flights alone; there’s no such thing as a cheap hotel in Nunavut, and food costs and on-the-ground transport brings the total costs even higher.

People living there deal with this daily. For most newsrooms, that’s just impossible. Coverage, even for northern reporters, gets stuck in the capital or done over the phone. Southern reporters write northern tales without ever setting foot on the tundra. And that’s a shame. One of the things that drives people to become journalists is a desire to tell stories — we like to rip into the body of a subject and squish around in the guts until we find the heart of it all. Can you really write about the North if you haven’t poured antifreeze down the drain after a shower so the pipes don’t freeze, tasted seal sliced bloody on sheets of cardboard on the kitchen floor or felt your eyelashes grow thick with frost while hunting the aurora?

We wanted to do it better. So our two organizations shared costs to send us to three Nunavut communities: Rankin Inlet, Iqaluit and Pangnirtung. The goal was to share content that complimented each other across platforms — I’d cover the print, she’d get the video, and somehow, between the two, we’d tell a deeper, richer story than we could on our own.

We got stuck in a blizzard in Rankin Inlet, and ended up selecting fabric and furs with the fire chief, so Jordan Tootoo’s sister could make us parkas (after all, Corrine Pilakapsi had already made all the custom parkas the fire department sport). We ate shawarma in Iqaluit and slid through stop signs in three languages and syllabics in a rented van with poor brakes we called the Struggle Bus in Pang.

And we learned to work together. Like a lot of journalists in small newsrooms, we spend most of our time working alone — suddenly, there I was, helping her rearrange someone’s living room to get a better background for a shoot, while she sat next to me during the kind of hour-long interviews I’m used to doing for magazine work.

We have very different styles, very different questions, and working together to see what got the other excited, how the other person drew interviews out, was like being back in school. It made the work better. But first we had to put aside any sense of competition. We had to trust each other to support each other’s work, and each other.

And that didn’t stop with the content. Over and over again, young people told us the one thing they wanted for the next 20 years in Nunavut was to be alive. Nunavut has one of the highest rates of suicide in the country; and its history of colonialism and intergenerational trauma colours everything. It’s a remarkably resilient and powerful place, but it’s tough to be a reporter there.

Getting back into the truck after an interview scooped your heart out with a melon baller and having someone else riding shotgun to literally keep your brain from melting was indescribably helpful. One thing working in Indigenous territories has taught me: we as an industry do an awful job preparing reporters to support our subjects and ourselves. We need to do better, and the first step could be just checking if other reporters are OK.

We deal with powerful and difficult subjects all the time; but working alone, you don’t often deal with what those subjects can do to your mental health, especially in an industry where the stereotype is a hard bitten, hard-drinking gumshoe who never cracks.

We got our interviews for our stories, but we got so much more: we got a glimpse of what it’s really like to live in Nunavut in 2019 by sitting in people’s kitchens drinking cups of Red Rose tea while the power flicked on and off, or watching the landscape disappear in a haze of snow and the sun slant off the frozen ocean.

Those are ideas and images that have coloured our work since. We also showed face. We made connections and met people in these communities, people who often distrust the media who so often get it wrong, or lose the context of stories and reporting because their experience is so removed from their subjects.

Canada has a lot of ground to cover in terms of reconciliation and decolonizing our media practice, but step one is actually turning up, and trying to do it differently.

It makes me wonder: if Porter had worked with a local journalist, would her story, which arguably has a bigger platform than most northern journalists can access, have been better? I don’t see how it could have made it worse. What she was missing was that connection, that understanding that comes from knowing a place and appreciating its people.

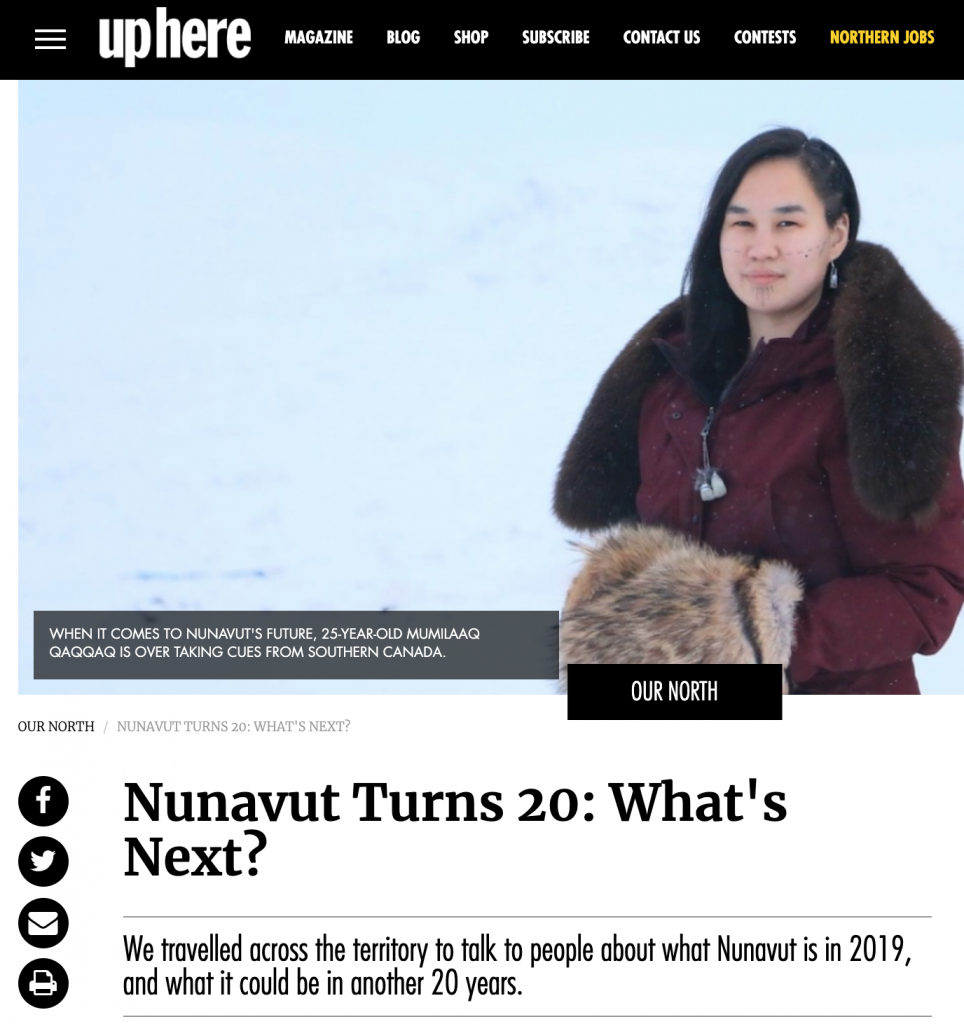

The North can be difficult; there is a history of trauma that rubs against almost everything. There’s social inequality, economic inequality, and as new Nunavut MP Mumilaaq Qaqqaq has been stressing since her election, human rights issues from education to clean water to food security that shouldn’t need to be discussed in a developed country like Canada, but are the reality of the North.

But what Porter — and I’d argue many parachute journalists — was missing wasn’t the facts, it’s the understanding that you can report on these issues with dignity, with compassion and with deeper understanding that can really paint a picture for readers, all over the world, of the North as it is, not some sort of twisted tragedy porn.

You can do a lot over the phone, but it’s much harder to develop that trust without being face-to-face. If collaboration means we get to do that, here’s for more sharing.