On a cold, snowy morning in January 2004, Khosro Shemiranie entered Concordia’s Loyola campus, looking for the journalism department. He’d been dreaming of studying to become a journalist for a long time. After a casual chat with a stranger who turned out to be a former department chair, however, he decided to skip studying, and started his own publication.

“I told her about my journalistic experience, and she said, ‘Would you like to teach a course in the department?’ I was confused,” Shemiranie recalled. “I told myself, ‘If they want me to teach here, maybe I shouldn’t study here.’”

At 16, Shemiranie left Iran for good and went to Germany. He wanted to become a journalist, but, worried about financial prospects, enrolled in dentistry and aimed to do journalism on the side. “But I soon realized that I can’t do both at the same time,” he said.

In 2001, he moved to Toronto and worked for the Persian magazine Shahrvand for a few years before moving to Montreal.

The idea of starting his own publication emerged when he was covering the 2004 United States presidential election for Shahrvand, after candidate John Kerry’s office refused his interview request. Frustrated because there was no independent Persian publication reputable enough to interview the American presidential candidate, he resolved to found one.

“For me, journalism is not a job. It’s my dream and my vocation,” Shemiranie said.

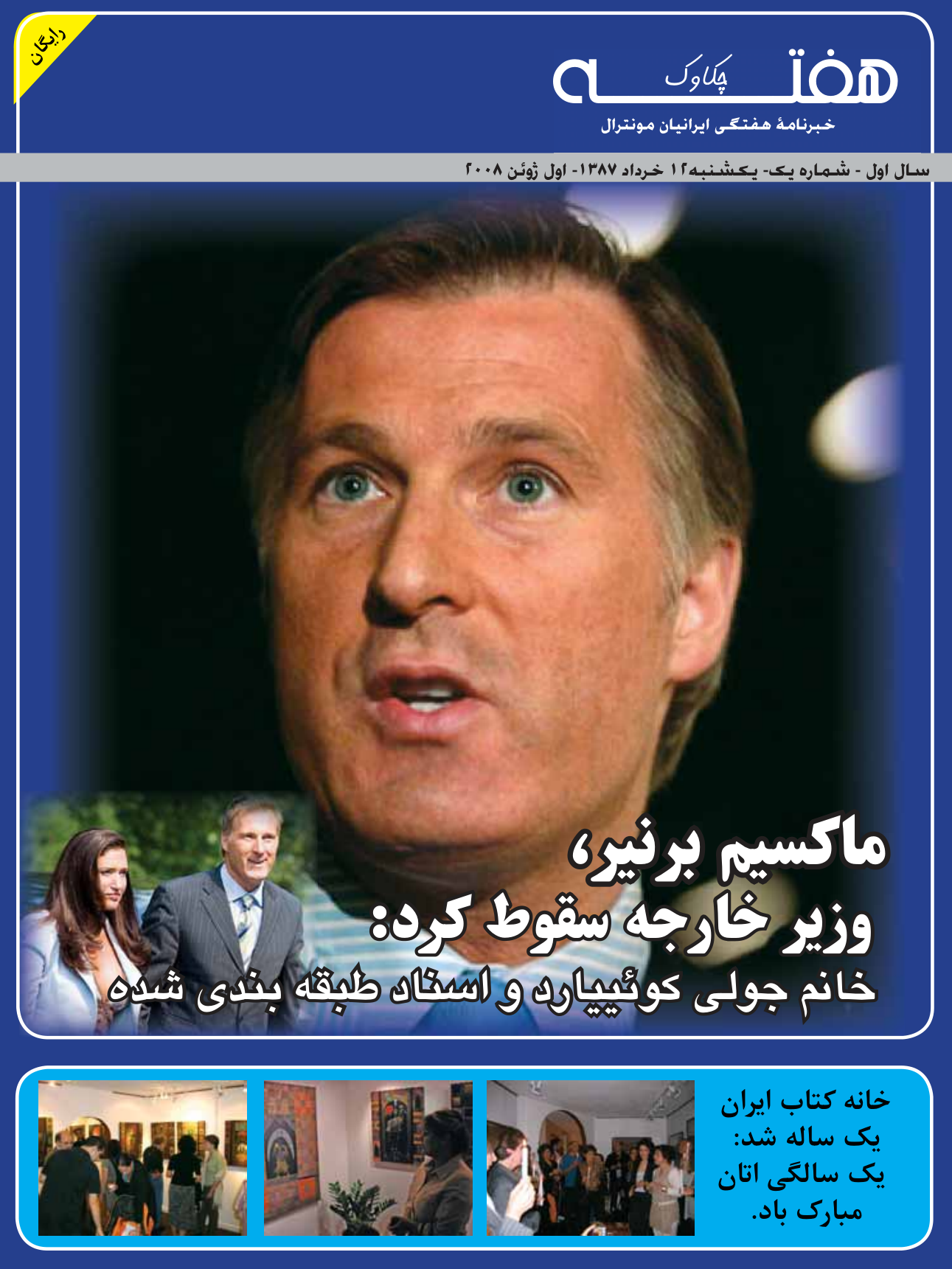

On June 1, 2008, he launched HafteH — or “Week” in Persian — a weekly magazine serving the Iranian community of Montreal.

HafteH is the only Persian weekly, print publication in Montreal, with a circulation of over 2,000, covering local news in Montreal and Quebec and publishing articles on literature, business and health.

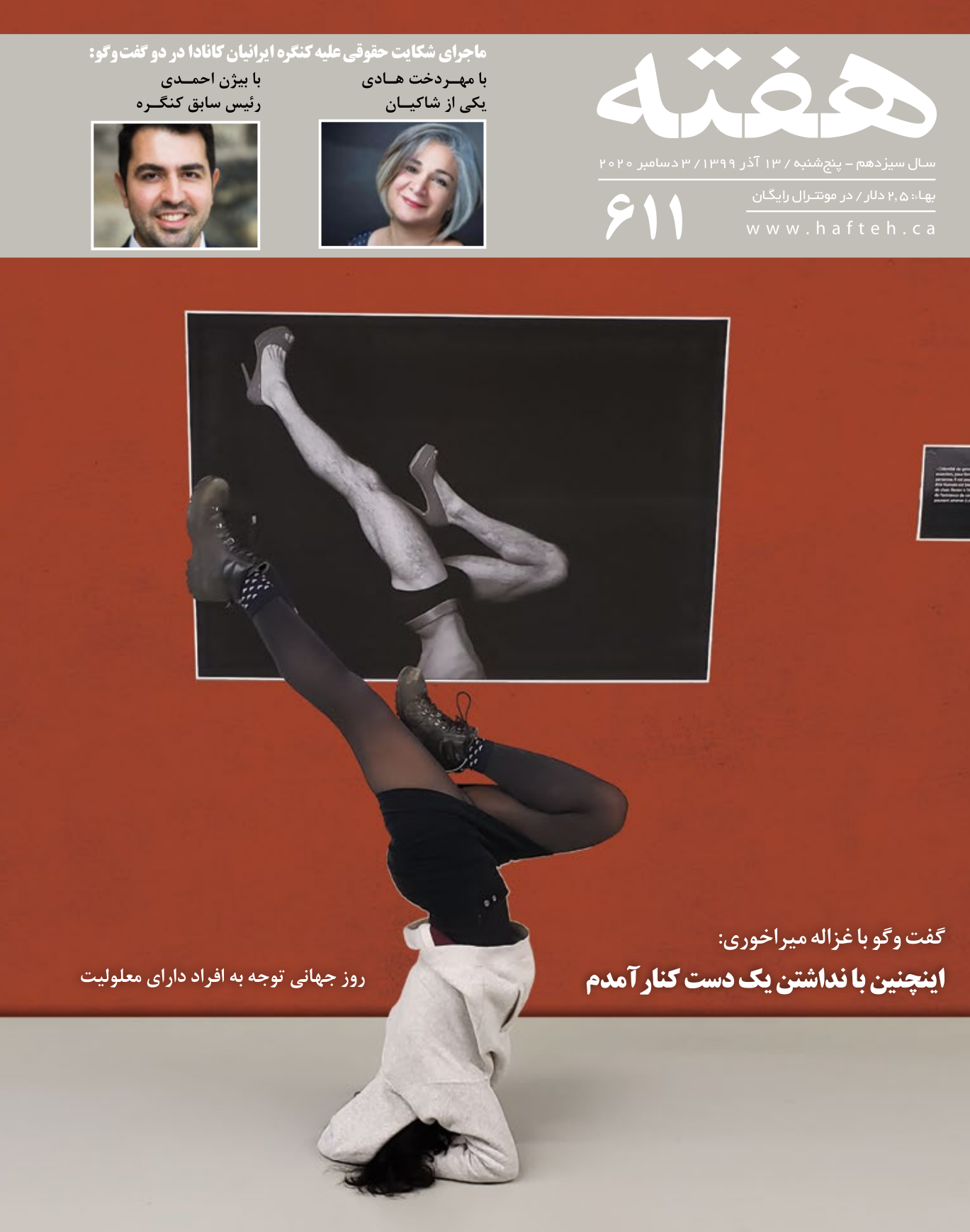

HafteH also covers news in Iran, focusing on minorities such as Baha’is and Afghans, who are often neglected by the Iranian mainstream media. But at the outset of its 14th year, HafteH is struggling to stay connected with younger Iranian immigrants, who are increasingly turning to a rapidly growing number of emerging Persian digital outlets.

HafteH’s trajectory and coverage

During its 13-year life, HafteH has skipped only four weeks each year.

Many Persian publications have appeared in Montreal but stopped after a year or less. Shemiranie believes the key to HafteH’s longevity was starting small and growing gradually. It started as a team of three, producing 24 pages per week, and now has a team of 20 people in total — most of them part-time employees and volunteers living in Canada and Iran — producing 80 pages per week.

Aliashraf Shadpour, an Iranian who immigrated to Montreal in 1996, said that the first issue of HafteH comprised a couple of pages stapled together. “I had never imagined that that featherless day-old-chick — which couldn’t walk — will become the mature magazine that it is today,” he said.

Even though HafteH’s print presence is unique, several strong, digital Persian news outlets have emerged in Montreal recently. A prominent example is Medad — or “Pencil” in Persian — which took off in 2018 and has over 10,000 followers on Instagram, three times that of HafteH.

“Today, HafteH has serious online rivals, and, to survive, it has to increasingly improve its online presence,” said Mahdieh Mostafaei, a former HafteH news editor.

HafteH is trying its luck in a new medium: podcasting. Its monthly one-hour podcast, Chacavac — or “Skylark” in Persian — was launched on July 1, 2020, and covers cultural topics such as history, society, literature and Indigenous issues.

Iranians’ opinions about HafteH

According to the 2016 census, nearly 30,000 Montrealers could speak Persian, and HafteH has its fans and critics among them.

“What I like about HafteH is that it covers all sorts of opinions from a wide political spectrum,” said Aisa Biria, who came to Montreal in 2010 to complete a PhD. “However, the quality of its pieces is not consistent and very much depends on the particular writer.”

Vahid Abdollahi, who came to Montreal in 2011 to study at McGill University, said that before the popularity of Facebook, he used to learn about the Iranian community’s events from HafteH. He also attended a creative writing workshop hosted at HafteH’s office. “They’ve always organized cultural events and workshops, and it’s easy to publish with them,” said Abdollahi, who published a short story in HafteH.

But their broad approach doesn’t always resonate with Abdollahi. “When I see they have a few pages of jokes and horoscopes, I get the impression that it’s not a serious magazine,” he said.

Shahrzad Tabatabaei came to Montreal in 2017 to study at Concordia University. She said that she’s learned a lot about Canada and adjusting to life in a new country. She even found her dentist through HafteH’s advertisements.

Tabatabaei said the diversity of HafteH’s contents is a double-edged sword. “On the one hand, no matter who you are, there is always something that interests you,” she said. “On the other hand, if your publication has too much diversity [in content and in political views], you lose the focus that a reader might like to see in a publication.”

Maryam Irani, HafteH’s former science editor, said HafteH is losing its focus. “Today, many of HafteH’s writers live in Iran,” she said. “It doesn’t look like a Montreal magazine anymore.”

HafteH’s challenges

One of HafteH’s major challenges has been maintaining an editorial team. “We have a relatively small budget. Most of our reporters either do not get paid or get paid very little,” Shemiranie said. “It’s hard to keep high-quality reporters with minimal payment.”

One of these reporters was the former editor Mostafaei, who worked for HafteH for eight years but left in 2019. “For me, HafteH was a safe place, like a family,” she said. “I left because I didn’t feel financially secure.” After leaving HafteH, she worked remotely for eight months at Independent Persian, a New York-based newspaper, before taking a retail job.

“Unfortunately, HafteH does not try hard enough to maintain a strong editorial team,” Mostafaei said.

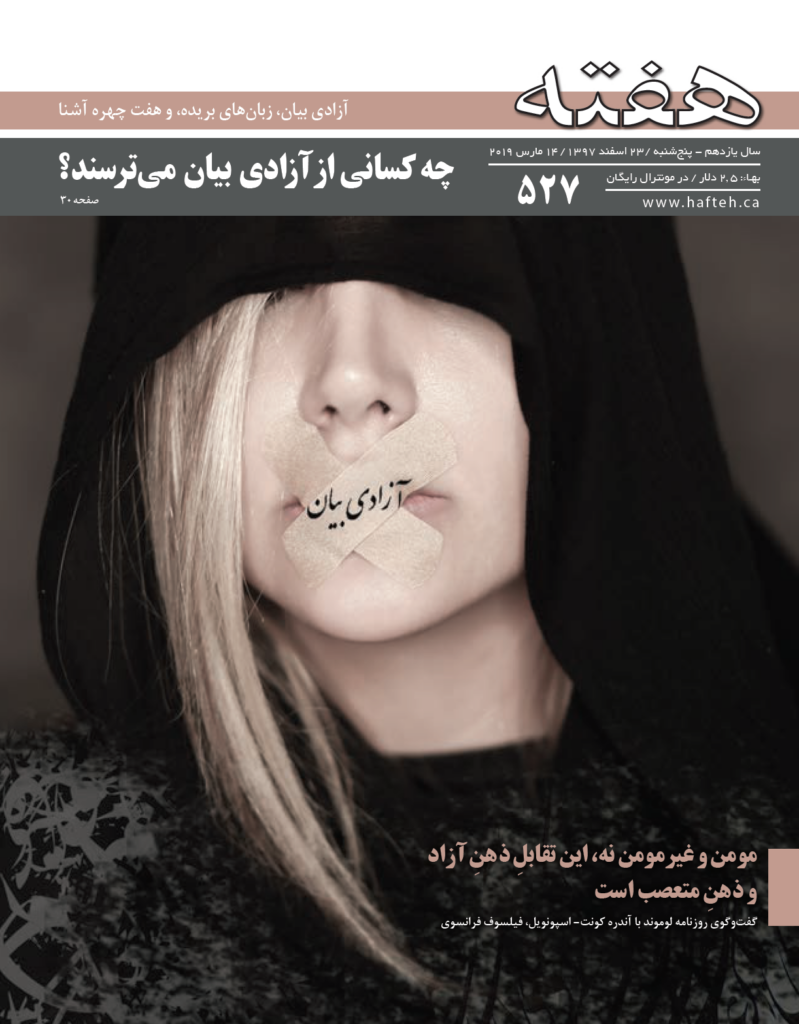

As a journalist, said Shemiranie, he greatly values freedom of speech. But there have been situations in which he compromised. In February 2019, the first part of a serial comic story was published on HafteH’s website in which the characters were God and the archangels, causing numerous calls and emails from Iranian religious institutions in Montreal that had taken offense, asking not to publish the story in the print issue.

After the first part of the series ran, instead of the remaining installments, Shemiranie published blank pages as a sign of protest. “I didn’t want to introduce more tensions into the Iranian community,” he said. “I sacrificed freedom of speech to avoid fracturing the community.”

Publishing for a minority group in a large city like Montreal has its advantages and disadvantages. “It’s like living in a village; I have spoken with most of HafteH’s subscribers in person and I get personal feedback from them,” Shemiranie said. “However, unlike French publications, I don’t have access to a huge number of advertisers or many good writers.”

As a publisher for an ethnic minority, Shemiranie aspires to be a mediator. “My goal is to build a bridge between the Iranian community and the rest of the Canadians,” he said.