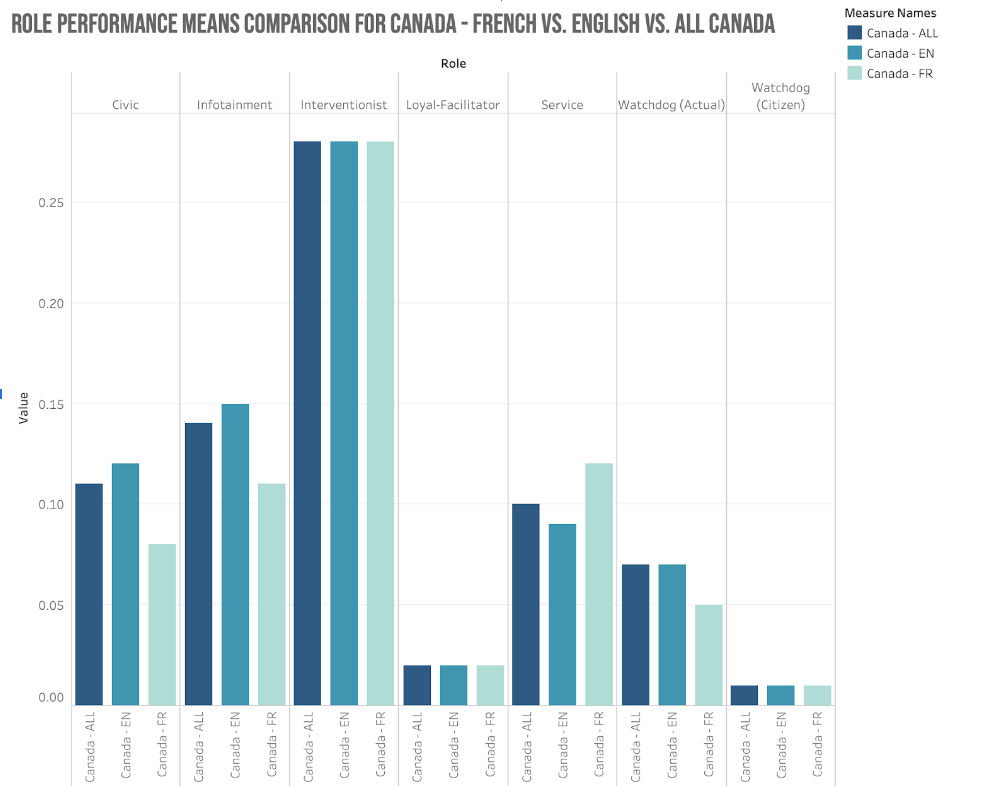

How does the journalism produced in Canada compare to journalistic ideals and journalism practice the world over? In a first-of-its-kind study in Canada, after poring over thousands of stories, we’re beginning to get a better understanding. Canadian journalism is audience-focused and more reliant on expert opinions than journalism in many other parts of the world. And while there are few distinctions between English and French news media in Canada, those differences are noteworthy. For example, English journalists in our sample referenced emotions and cited community members’ (what the study refers to as “citizens”) voices more than French journalists.

The Journalistic Role Performance project is an international partnership with 36 other countries. This is its second wave; Canada didn’t take part in the first. Researchers of this complex study collected almost 150,000 stories (3,700+ in Canada) published in 2020 from hundreds of media organizations in the Global North and South, and used a tested methodology to see what journalistic roles were present in those stories: watchdog, interventionist, civic, service, infotainment, and/or loyal facilitator.

Then, we compared what was found in that content analysis to a survey of journalists from around the globe that measured the importance they placed on these roles and how often they perceived these roles were being performed in their newsrooms. In Canada, findings were further contextualized with interviews with journalists. Sites of study had to be of national relevance. We looked at 12 mainstream news outlets:

Television: CTV National News; CBC: The National; Global National; TVA Nouvelles 22h

Newspapers: Toronto Star; National Post; Globe and Mail

Radio: CBC Radio: World at Six; ICI Radio-Canada Première: L’heure du monde

Online media: La Presse; CBC.ca; HuffPost Canada (which closed in March 2021)

All types of news stories, from court reporting to politics to sports to lifestyle and entertainment were examined, as long as the stories were produced by a journalist who worked for one of the sites of study. Stories published or broadcast that were solely generated from another news outlet or a news agency, such as Canadian Press, were not included. Neither were editorial and opinion pieces. Preliminary findings of the Canadian team were recently published in Facts and Frictions.

One practice that stood out was the use of experts in Canadian reporting: they were seen twice as often than the average of other countries in the study. However, all the former journalists on the research team felt getting an expert — defined by the JRP as “specialists in their specific area” — to give context was a newsroom norm in Canada, and seemed even more pertinent within the context of a pandemic. Here’s what else we’ve found so far, with a brief explanation of what each of the journalistic roles looks like in practice.

Watchdog

The watchdog role is one that is central to journalistic ideals: holding power to account. However, it’s also the role where we see the biggest gap between its stated importance to journalists, their conception of how often it’s done and the amount of watchdog reporting that actually happens. Journalists interviewed for the study pointed to lack of resources as an important factor in what and how stories were covered. Talking about holding power to account, one reporter said, “I don’t expect all journalists to be able to live up to their ideals. I don’t think we have an industry structured in a way that supports them in that. So I don’t see people who have time to do that as morally superior to people who don’t have time to do that.”

This lack of resources also might explain the minimal amount of investigative reporting found in the stories analyzed in Canada and internationally. Shrinking newsrooms and increasing workloads were highlighted by another reporter who said, “When you read the job descriptions for what is expected it’s like you’re asking for a superhero.”

Civic Role

The civic role focuses on amplifying the viewpoints and rights of citizens. It’s often seen in stories where a journalist might cover a protest or get the opinion of ordinary people on political decisions. Journalists in Canada performed the civic role more often than almost all other countries – ranking second out of the 37 participating in the JRP study.

How the JRP codebook defines journalistic roles

Loyal facilitator: Journalists who co-operate with those in power, and accept the information they provide as credible and those who support their nation-state, portraying a positive image of their country.

Where Canada ranks internationally: 23

Infotainment: Using different stylistic, narrative and visual discourses in order to entertain and thrill the public. Here, journalism borrows from the conventions of entertainment genres by using story-telling devices and establishing characters and setting. This may include the use of emotions, which could be expressed by a source or the journalist.

Where Canada ranks internationally: 8

Watchdog:

The watchdog role seeks to protect the public interest and to hold various elites in power accountable, serving as a “fourth estate.”

Where Canada ranks internationally: 10 (for watchdog “actual” role.)

Interventionist: Journalism where the journalist has an explicit voice in the story, and sometimes acts as an advocate for individuals or groups in society. Based on JRP data, in Canada, interventionism is less about a journalist’s viewpoint, and more about interpreting events based on available evidence.

Where Canada ranks internationally: 3

Civic:

A focus on the connection between journalism, the citizenry and public life and helping audiences make sense of their own communities, and on how they can be affected by different political decisions.

Where Canada ranks internationally: 2

Service:

Journalism that prioritizes this role provides help, tips, guidance and information about the management of day-to-day life and individual problems (news you can use).

Where Canada ranks internationally: 5

But there were certain elements of reporting within this role that drove its high ranking, including the use of citizen reactions and references to how political decisions might impact a particular social community (for example, based on race or gender). There were also differences in reporting between French and English news organizations. For example, English media had more stories referring to local impact, which we found somewhat surprising as we were studying primarily national media and had expected relatively more regional reporting in Quebec.

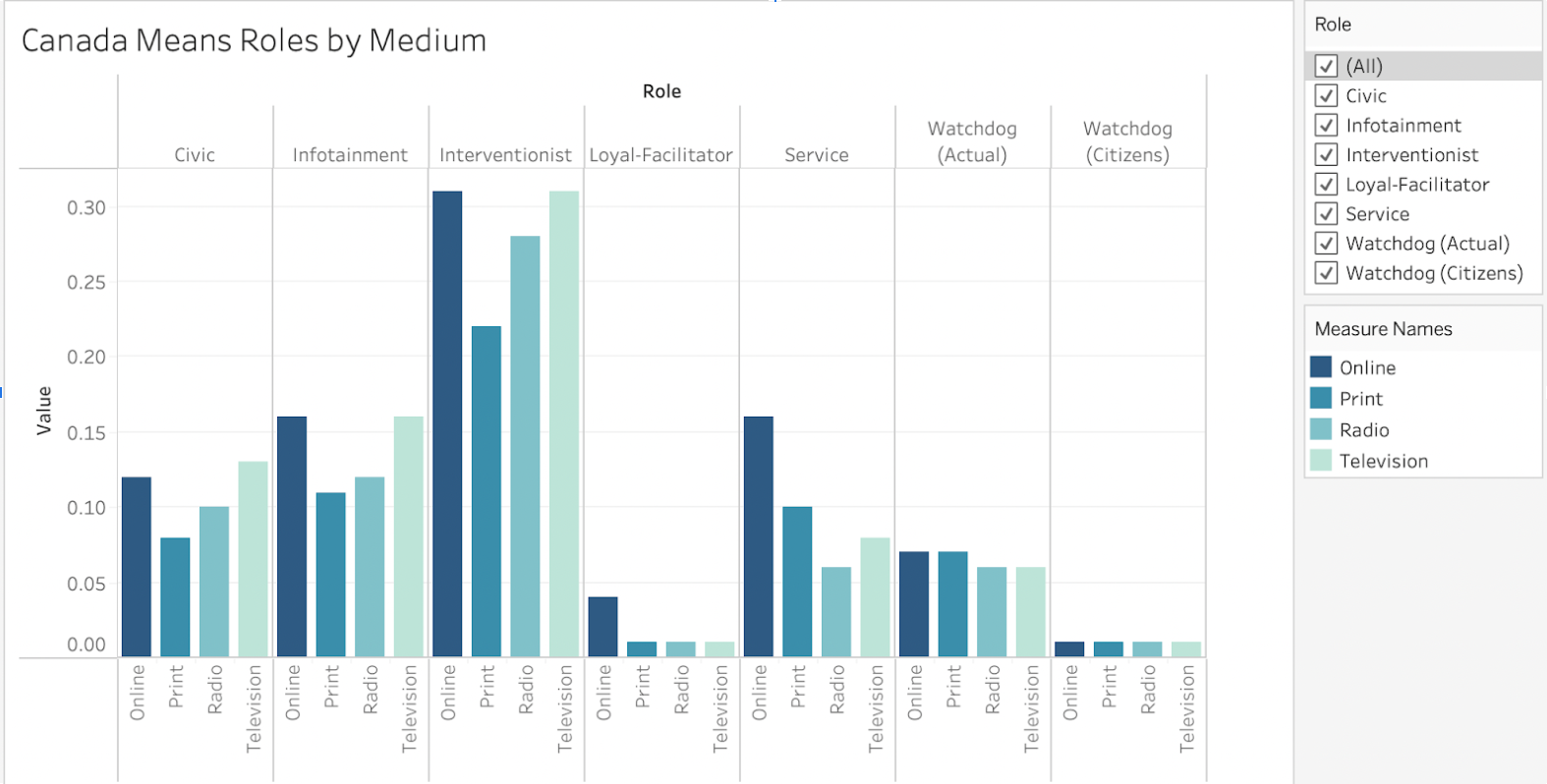

Platform of delivery also mattered. For example, TV news had the most civic-style reporting overall, with online close on its tail. Broadcast (radio and TV) content included more information on citizen activities, such as protests. Citizen voices were found least in newspapers. Online news had more reporting that included information educating people on their duties and rights as citizens compared to all other platforms. In the civic role, we also saw the second-biggest gap between its perceived importance and how often it was performed.

Interventionist

With the interventionist role, a journalist is present in a story’s narrative, something measured, for example, by use of first-person or describing cause and effect without quoting a source. This is another role where Canada has a high global ranking, third of 37 countries. There were two particular facets of interventionist-style reporting that drove this result: interpretation and the use of qualifying adjectives. Words like “epic” referring to a snowman or “apocalypse” referring to a budget were both coded as qualifying adjectives. But those two examples show what might be an issue with the measure – while “epic” may be a good descriptor for a giant snowman, the use of “apocalypse” seemed more exaggerated and opinion-based. Overall though, after analysis, we feel the interventionist role in Canada is less about a journalist’s viewpoint, and more about helping the audience understand complex events or issues.

Also of note with regards to the interventionist role — it represents the smallest gap between ideals and practice compared to all of the roles. Still, the journalists we talked to ranged in their opinions on what was considered balanced reporting. For example, one said, “I still think you should be impartial, just tell the story. Now columnists have their opinions and that’s a different thing.” Another said, “I don’t agree with the objectivity part and giving equal space to all parties in a story. That’s fallen by the wayside, I would say, and that’s good.” These remarks reflect shifting attitudes towards traditional expectations of “objectivity” being grappled with across the industry.

Infotainment

In the infotainment role, entertaining the audience can take priority over informing them — but this doesn’t necessarily mean facts and reporting fall by the wayside. Sometimes stories may cross over into sensationalism, where there is exaggeration and unwarranted use of drama. But often, infotainment means engaging the audience on fact-based reporting utilizing basic storytelling techniques, such as references to sources’ personal experiences and emotions.

Infotainment shouldn’t be seen as a singularly negative ranking when you take a closer look at the way stories are coded. For Canada’s ranking, use of emotions in a story, either by someone being quoted or by the journalist, was seen nearly twice as often compared to most other countries and more frequently in English media and television news. Examples of emotion range widely, from a hard-news story about a family member expressing anger at lack of access to medical care for a teen who died in custody, someone crying in a television story, or the use of words like “happy” in a story about a young Canadian performer on American Idol. The fact that emotion is expressed in a story does not, necessarily, mean that a reporter is trying to “entertain” the audience in a way that is inappropriate. Stories in this study are being coded based on research literature that defines six basic emotions: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness and surprise, often used in entertainment-based content to make a story more engaging by giving the reader or viewer a sense of how something feels. However, another factor that contributed to overall scores, use of sensationalism, was much less frequent in Canadian stories in our sample compared to most other countries, although seen a bit more in French media. Overall, there is significant infotainment in Canadian reporting – we ranked eighth out of 37 countries.

The small gap between the importance journalists placed on the infotainment role in their survey answers and how often it is actually performed suggests journalists in Canada are somewhat accepting and aware of how infotainment is used. And our analysis overall suggests that news can be both entertaining and informing – multiple roles can be at play, even within one story. “Let’s make sure we are the first ones there with information that is useful to them and contextual and interesting and you know, fun, when appropriate, serious when not,” said an editor interviewed.

Service Role

Service is the “news you can use” of journalistic roles – the type of reporting where journalists offer practical advice and recommendations. Canada ranked fifth worldwide in this style of reporting. This could be another area where the pandemic impacted the prevalence of a particular journalistic function. Due to the timeframe of our collection (over the course of 2020 as the pandemic erupted) there were frequent stories about, for example, the best masks and hand sanitizers.

Service journalism was also a role that seemed highly impacted by the platform of delivery. The prominence of formats like listicles could help explain why more stories online offered tips and advice, compared to other platforms. Consumer information was also seen much more often in online and in print, compared to television and radio. News that involved impact on everyday life was most common in online content and television reporting, but seen significantly less in radio and print. In terms of the gap between ideals and practice, it was moderate – but the role was more important to journalists surveyed compared to how often it appeared in the stories studied.

Loyal facilitator

Acting as loyal facilitators, journalists support the narrative of governments or elite members of society. Based on the stories we coded, it rarely happens in Canada and, from an international perspective, has little presence in most countries. It’s more common, though, in places with lower political, legal, and economic freedom. In the JRP study, an example of the loyal-facilitator role in action would be a sports reporter talking up a star player. It’s also coded for stories that support people in positions of power, including politicians. Keeping in mind the scarcity of the loyal-facilitator role within the Canadian media sampled, and the unprecedented circumstances of the pandemic, there was a very slight increase in this type of reporting in Canada when it came to COVID coverage. An example would be a reporter supporting government initiatives around masking, outside of citing a public health official.

As one journalist described:

“If a public health authority person says, listen, you have to avoid big crowds or cohorts … that’s good enough for me, and I’m going to push that message and reinforce it, you know, if I’m asked … I don’t feel pressured to do that. I just think it’s the responsible thing to do as a human being.”

It’s also of interest that subsequent to that minimal increase in loyal-facilitator reporting in COVID-related stories over the course of the pandemic, other research found a drop in audience trust in news and increased perceptions that media were not acting independently of political and business pressures.

Based on our sample of stories, there is such little evidence of the loyal-facilitator role in Canadian reporting that these perceptions concerning political pressures, or what might be described as inappropriate or unwarranted support of government narratives, do not seem to be supported. As noted previously, though, our sample only included news stories, not more polarizing opinion and editorial pieces. However, there is lots of research to show that the audience doesn’t distinguish between news and opinion, even when content is labeled, or between news and native advertising. Therefore, news organizations need to consider how all of the content they publish might impact audience perceptions. From a platform perspective, the loyal-facilitator role was more notable in online content in Canada.

More to come

We have collected a lot of data over the past few years, and there’s much more we hope to do with it. For example, we have evidence that when it comes to police and crime stories, based on analysis of the factors that measure the interventionist role, such as the use of qualifying adjectives or interpretation, this role is more prevalent in French than English media. Overall, the interventionist role is performed much more frequently in stories related to campaigns and elections in Canada. So are certain journalistic roles, and specific aspects of those roles, more prevalent in certain types of stories and does that differ based on language?

The information we’ve been gathering can also help us better understand what student journalists need to know before heading out into the field and, perhaps, most importantly, how to improve the narrative of an industry fighting to retain its relevance and maintain trust with the audience.

There will be an international conference at Toronto Metropolitan University this spring, where scholars from around the world will come to share their research on how journalistic roles are changing in these transformative times. Journalists will also be invited to both hear about the research and provide crucial context from a practice perspective. This is because building better bridges between academics and newsrooms makes for better research and, potentially, better journalism. If you’re a journalist who’s interested in attending, just let us know.

Nicole Blanchett is the principal investigator of the Canadian branch of the Journalistic Role Performance project and an associate professor in the School of Journalism at Toronto Metropolitan University.

Anna Maria Moubayed is a research assistant for the Canadian branch of the Journalistic Role Performance project and an undergraduate student in the School of Journalism at Toronto Metropolitan University.