Labour organizations and advocates for freelancers’ rights, in an inherently disaggregated part of the industry, agree on one thing: the fight for improved conditions must be done together.

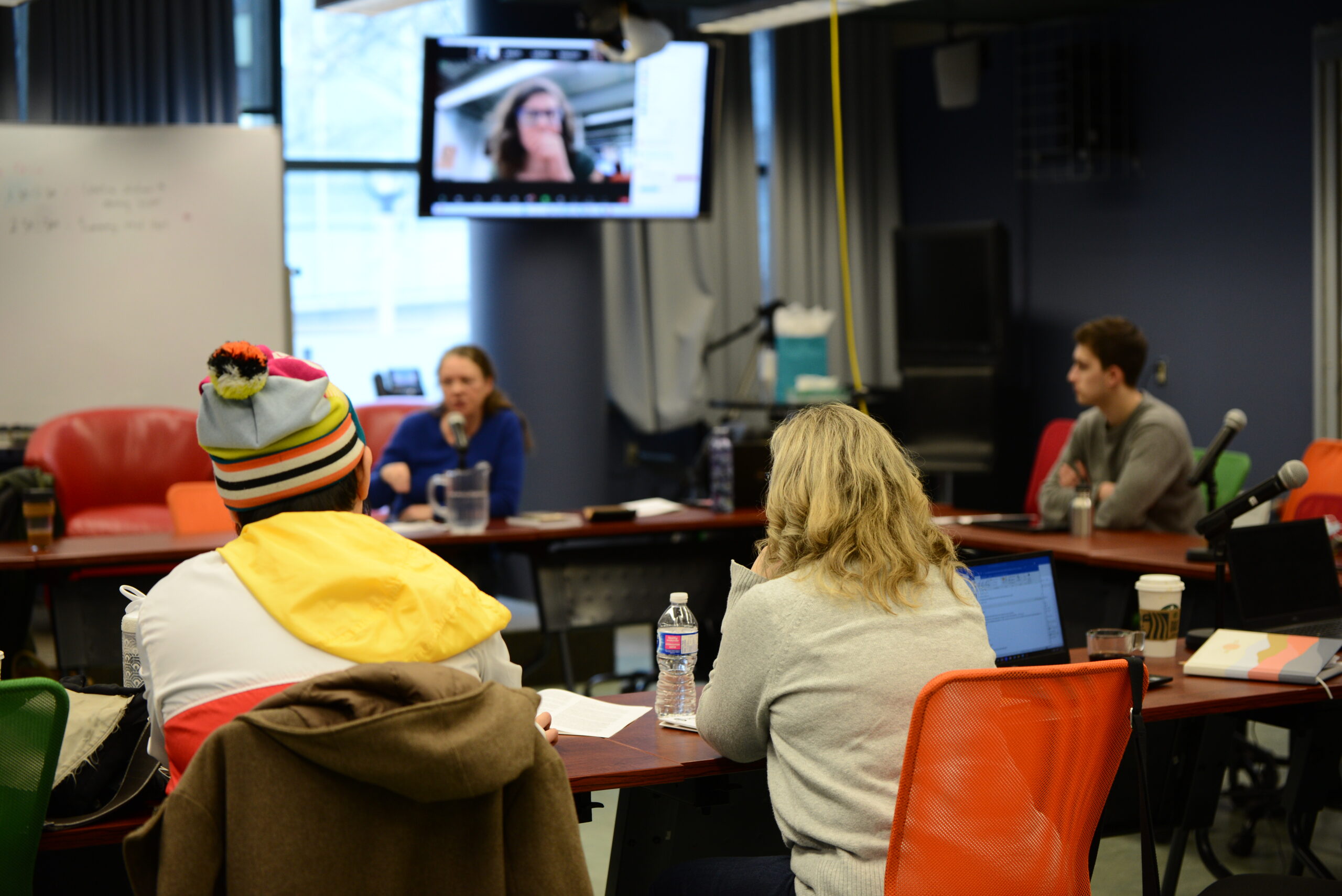

About 20 journalists, editors, photojournalists and students convened at Toronto Metropolitan University on Feb. 3 at a gathering hosted by the Canadian Freelance Union and the United Photojournalists of Canada to consider strategies for securing improved working conditions, compensation and benefits for media freelancers.

While freelancing was once a manageable way to break into full-time roles, or to flexibly bring one’s expertise to a variety of outlets, “now we look at it as precarious work,” said Randy Kitt, media director at Unifor.

As conditions continue to tighten around the journalism labour market, many are increasingly pushed into often low-paid contract work or leaving the industry entirely. The looming spectre of AI, particularly around image production and copyright, raises flags for the future of freelance work.

UPoC, which was formed in 2020, helped negotiate the first pay increase for Globe and Mail photojournalists in decades. Nearly 30 per cent of Québec freelancers reported making minimum wage or less, according to a survey from the Association des journalistes indépendants du Québec, published in December.

Among those in attendance at the meeting were representatives from Unifor, the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists, and the Canadian Media Guild.

Throughout the day-long session, attendees laid out frameworks for labour organizing and discussed strategies for collective action moving forward. Here are some of the key takeaways and commitments.

Unique challenges for freelancers: Attendees acknowledged that advocating for freelancers as a class of journalists has historically been challenging. Traditional means of organizing, such as collective bargaining, do not apply easily to freelancers who typically work for several publications or news agencies.

“The massive loss of journalism jobs in the last decade, coupled with the fact that the history of these jobs is associated with prestige, has created a sort of perfect storm for employers to reduce full-time work and create large pools of precarious jobs,” said Kitt during a presentation on organizing freelance workers.

These challenges are reflected in the current work of the Canadian Freelance Union. Summit organizer and CFU executive Nora Loreto said that while they’ve never lost an individual case when supporting freelancers, they’ve struggled to secure victories at institutional levels. But collective actions such as declining work during times of publication need may be effective moving forward as a way to build and leverage collective power.

Accreditation for freelance journalists: Freelancers lack of affiliation with a single media organization also creates barriers in their work. One proposed solution for this is to implement a model for unionization similar to ACTRA, which gives workers access to different levels of membership depending on how many confirmed credits they receive in creative productions.

Unions for freelance journalists could create a similar structure, in which a freelancer could become formally accredited by the union after a certain number of bylines in reputable outlets.

Bill of Rights: Inspired by the Photo Bill of Rights, a series of calls to action by grassroots organizations to build a “more inclusive and equitable visual media industry,” labour organizers at the summit discussed creating a similar bill of rights for freelance journalists and creative workers. The proposed bill of rights would include calls for minimum pay rates for freelancers, reasonable timelines for remuneration and standards for communication and overall working conditions, among other things.

Grading publications’ labour practices: The parties present supported the idea of grading the labour practices of various media outlets and publications. This would entail an investigation into how much publications pay for freelance articles, how long they take to settle invoices and the overall culture and working relationships developed by editorial teams.

“That could be something that we do very, very soon while we try to do broader … consultations or roundtable discussions,” said Loreto.

This scorecard for publications would be a way to both call out bad actors in the industry who pay poorly for freelance work and also celebrate the media outlets that espouse fair and transparent practices and improve over time.

Movement building: Ultimately, building enough momentum to effect industry-wide change will require significant time and resources, which is limited for individual organizations. However, the labour organizers at the summit committed to continuing to work together as a collective and create bridges and solidarity in their own networks.

“This Canada-wide perspective is critical,” said Justin Gniposky, director of organizing for Unifor National. “Without a wholesome discussion, it’s just what our view is — or the CFU’s view, for that matter — and it doesn’t take into account all these things.”

Notably, the parties agreed to gather freelance journalists from across the country in a series of discussions to develop a more holistic understanding of the most pressing issues and priorities for freelancers today.

Kitt, the media director at Unifor, emphasized that a collective approach was key.

“We firmly believe that we are stronger together, and divided we fall,” he said.