J-Source launched the Canada Press Freedom Project in 2022 to help increase understanding of media rights in Canada. The CPFP maintains a public database dating back to 2021 of press freedom violations across 12 categories, from denials of access to arrests, online threats and more. We’ll feature periodic notes on trends and other updates from the CPFP. This article first appeared in the J-Source newsletter.

In an October court filing, the RCMP claim – without citing evidence – that photojournalist Amber Bracken* wasn’t working as a journalist when police arrested her in November 2021 in B.C.

Bracken and The Narwhal are suing the RCMP, who arrested the photojournalist while she was covering a police raid on Wet’suwet’en territory for the online publication. (The charges against Bracken, who was arrested with documentary filmmaker Michael Toledano, were dropped in December 2021.)

The RCMP responded in court to the lawsuit in October. Their lawyers argue that journalists are not exempt from an injunction banning protests against a recently completed pipeline that passes through Wet’suwet’en territory and underneath the Morice river – but they’re also claiming that Bracken was “aiding or abetting” protesters.

The RCMP acknowledge that an editor at The Narwhal told police the day before the raid that Bracken was in the area, and also acknowledged that a senior RCMP officer told the publication that she would let officers in the field know Bracken was working in the area.

But in the court response, RCMP lawyers claim that Bracken “was not engaged in apparent good faith news-gathering activities” – a suggestion The Narwhal has rejected, and which is not supported by any evidence.

The RCMP did acknowledge that Bracken was on assignment as a journalist when she was arrested, but they claim that her “actions went beyond her role as a journalist.” The RCMP response doesn’t explain this claim further, apart from the fact that Bracken was in an area subject to a court injunction.

The phrasing of the RCMP’s response echoes language used in the 2019 Justin Brake decision, which affirmed that journalists may cover events of public interest in areas where an injunction is in place – and particularly protests around Indigenous issues – if they are working in “good faith.”

The judge in the Brake decision defined criteria to help establish whether a journalist should be able to continue to cover events in an injunction zone. The criteria include whether the journalist is “engaged in apparent good faith in a news-gathering activity of a journalistic nature,” and is “not actively assisting, participating with or advocating for the protesters” or “aiding or abetting” them.

RCMP lawyers also argue in the filing that “there is no general exception in law that exempts a member of the media from complying with valid court orders.”

The Canadian Association of Journalists called the RCMP response “utterly dismaying” and said it was “the most farcical demonstration yet of the RCMP’s efforts to restrict press access and stifle journalistic work.”

Reporters sans frontières said in a statement that it “firmly rejects” the RCMP’s claims. “The episode highlights the need for greater police training on press freedom,” RSF wrote.

In August, B.C. RCMP also interfered with Bracken and journalist Brandi Morin while they were covering a raid on a protest camp in the woods on Southern Vancouver Island.

Police threatened to arrest Morin, who, along with Bracken, was on assignment for Ricochet and IndigiNews. An officer told Morin and Bracken that, for their safety, they needed to leave what he described as a “media exclusion zone.” One of the officers grabbed Morin after threatening her with arrest, she said.

Exclusion zones have become a key tool used by police to deny access to journalists (H.G. Watson wrote a comprehensive explainer earlier this year).

The B.C. RCMP used them extensively during the Fairy Creek old-growth logging protests on southern Vancouver Island – so much so that, in response to a media lawsuit, the B.C. Supreme Court ordered police to stop interfering with the press. But the August incident suggests that message still hasn’t gotten through.

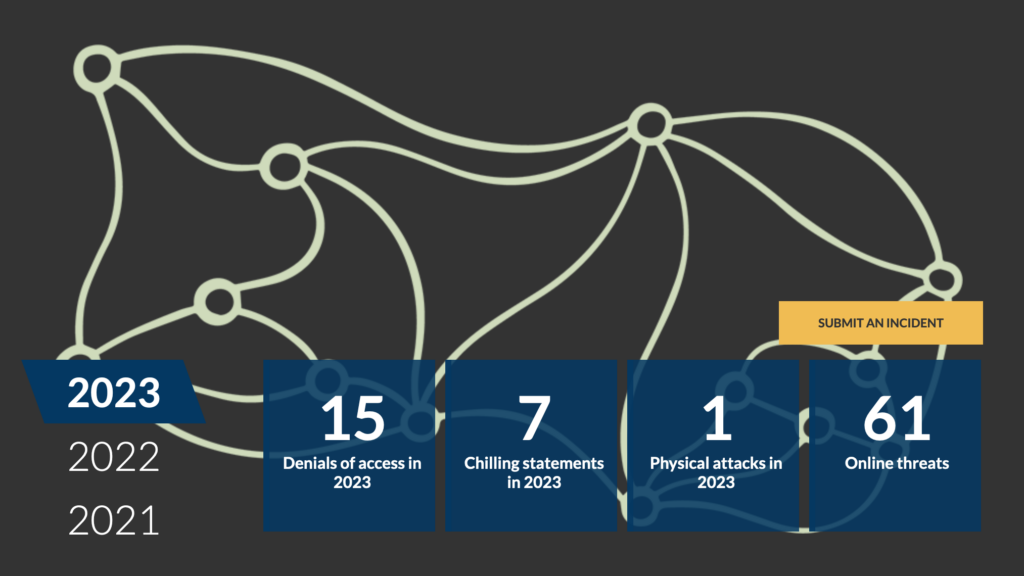

So far in 2023, CPFP has documented a total of 15 access denials. Police were involved in more than half of the incidents – RCMP, as well as local police in Vancouver, Montreal and Edmonton. The journalists involved in three incidents reported that police threatened them with arrest, and in four incidents, journalists reported that police used or threatened them with physical force.

In 2022, the CPFP recorded six incidents of access denials and 24 in 2021. Of those, nearly all (17) took place during anti-logging protests on Vancouver Island, when media workers were routinely denied access and threatened with arrest, and in some cases, arrested and charged.

To learn more about media workers’ rights and risks while covering protests, visit the guide produced by the Committee to Protect Journalists (a partner of the CPFP) and the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

*Amber Bracken is a member of the Canada Press Freedom Project’s advisory board.

Have you been denied access to cover a story, or experienced any other unreasonable interference or threat while working? Sharing incidents can help media workers, researchers and more by helping the CPFP provide the most complete picture possible of press freedom violations across Canada.