A recent cover story in Canada’s History showcases 17 first-hand accounts of “what it’s like” to be in that moment.

By Julie McCann, Field Notes Editor

Mark Collin Reid loved learning about what it feels like to be bitten by a shark. He was a young reporter at the New Brunswick Telegraph-Journal when he first read Esquire magazine’s first-person series about unusual experiences called “What it feels like…” and the idea stayed with him.

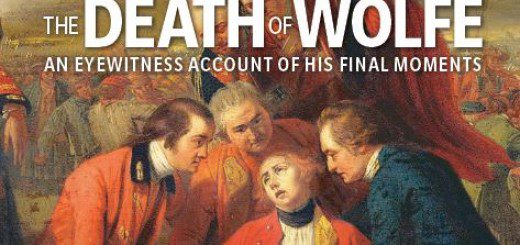

More than a decade later, as the editor-in-chief and director of content for Winnipeg-based Canada’s History magazine, Reid spotted an opportunity to adapt the concept for his own readers. The result is the cover story of the August-September 2014 issue called “What it’s like.” The 10-page piece includes first-hand accounts from people such as a man who was with Major General James Wolfe when he died, a former resident of Nova Scotia’s Africville and a teenager quarantined for cholera in Quebec City in the 1800s.

Reid’s hope is the piece can act like a virtual time machine: it aims to drop a reader in beside a person—who happens to be dead—but who is sharing his or her story. “It drives me nuts when people say they can’t connect with people from the past,” Reid said. “They can’t put themselves in their shoes. It’s almost like they’re aliens from another world.” But maybe here, using the person’s own words, a reader can empathize with them and feel how alike they really are.

Reid’s hope is the piece can act like a virtual time machine: it aims to drop a reader in beside a person—who happens to be dead—but who is sharing his or her story. “It drives me nuts when people say they can’t connect with people from the past,” Reid said. “They can’t put themselves in their shoes. It’s almost like they’re aliens from another world.” But maybe here, using the person’s own words, a reader can empathize with them and feel how alike they really are.

The back story

The spark: More than a year ago, Reid fell into a book he found in the magazine’s library by a fur trader reminiscing about his time in northern Manitoba. (Formerly known as The Beaver, the publication has been around for more than 90 years and has an eclectic book collection.) “It was about his memories of a wild Christmas dance party that they had with the local Aboriginal and Metis people,” Reid said. It featured fiddling, men tossing off their sashes, women hiking up their skirts and everyone dancing until the sweat poured off them. “It ended off with all of them running out into the snow banks to cool off.” Although the man’s story didn’t make the final collection—Reid joked there should be a director’s cut so it can be included—it made him feel fully alive. Reid wanted to bring this feeling to his readers too.

Structure: The piece was always meant to have a “compartmentalized” structure. After a short introduction, the article features 17 first-hand accounts, each with a summary and post-script by Reid. It’s notable that the magazine is currently doing a “refresh”—not a redesign—and its layout is being tweaked for the December issue. Stories structured this way complement traditional long reads and help them try to reach a broader audience. “If you’re busy and you’re trying to get the kids to soccer practice, you can tackle an article like this and be entertained, intrigued and a little bit informed,” explained Reid. “But you can also put it down and pick it up later.”

Cast of characters: Not surprisingly, narrowing down the list of whose shoes Reid wanted readers to wear was tough. He wanted a cross section of people living in Canada—geographically, culturally, historically, topically—in an effort to maximize the possibility a reader would connect with someone. A particularly gruesome and militarily significant first-hand experience from Samuel de Champlain’s book Voyages, for instance, was cut from the final collection. “My goal was not to repulse people,” said Reid. A short letter from a young boy receiving then-novel insulin for diabetes, however, made the cut: “Dear Dr. Banting: I wish you could come and see me. I am a fat boy now and I feel fine. I can climb a tree. Lots of love, from Teddy Ryder.”

Creation

Writing: Although he’s the magazine’s editor, Reid still aims to write one or two features a year. Although he loves it, he doesn’t get to write as much he would like. (Note: he also has a book published by HarperCollins coming out in October called Canada’s Great War Album.) In this case, however, the challenge was length. When he was a newspaper reporter for a broadsheet, Reid loved to tease the tabloid reporters about their short stories. “Now I actually realize it’s more challenging to write short than it is to write long,” he said with a laugh.

Editing: When he presented his first draft to senior editor Nelle Oosterom, the piece was running about 6,000 words. “She’s honest,” he said. It came back full of red ink and Reid was happy: he knew her suggestions would make it stronger. She also helped him shave off about 1,000 words.

Design: A lot of thought went into which stories to pair up on which pages and who should follow whom. “We didn’t want all of the war ones together,” he said. “When you lay things out it’s like a jigsaw puzzle: how can we make this fit?” Reid worked closely with art director James Gillespie on the package.

Cover: Over the years Reid has learned the cover’s importance: “You need to sell magazines,” he said. What sells for Canada’s History is “meat-and-potatoes history.” This includes military themes, such as the Wolfe cover of this issue. But it wasn’t the original concept. Initially they’d wanted a montage of a bunch of characters—Terry Fox running beside a skating Rocket Richard, for instance—and together they’d all be walking side by side toward the reader. The fact that not all paintings and photos were of the same quality meant the concept just didn’t work. Neither did the second concept: a series of squares of all of the storytellers’ faces, similar to what appears on the piece’s opening spread. When they finally opted to focus on one character and image on the cover—Wolfe’s death—they all felt the “this is the one” moment.

Post production

Reader reaction: So far, it’s been generally positive. Several readers have reminded the magazine, however, that the painting of Wolfe is nothing like what the scene would have actually looked like. “The guy who painted it, Benjamin West, was a bit of a hustler,” Reid said. “He basically said, ‘I will paint you in the painting for 100 pounds.’ There are maybe actually two people who were actually there, the rest paid to be there.” The editors, of course, knew this fact, but it still suggests something positive for Reid’s story: these readers, at least, are connecting well with people who lived before them.