In 2014, 221 journalists were imprisoned worldwide, says the Committee to Protect Journalists.

By Sameera Raja

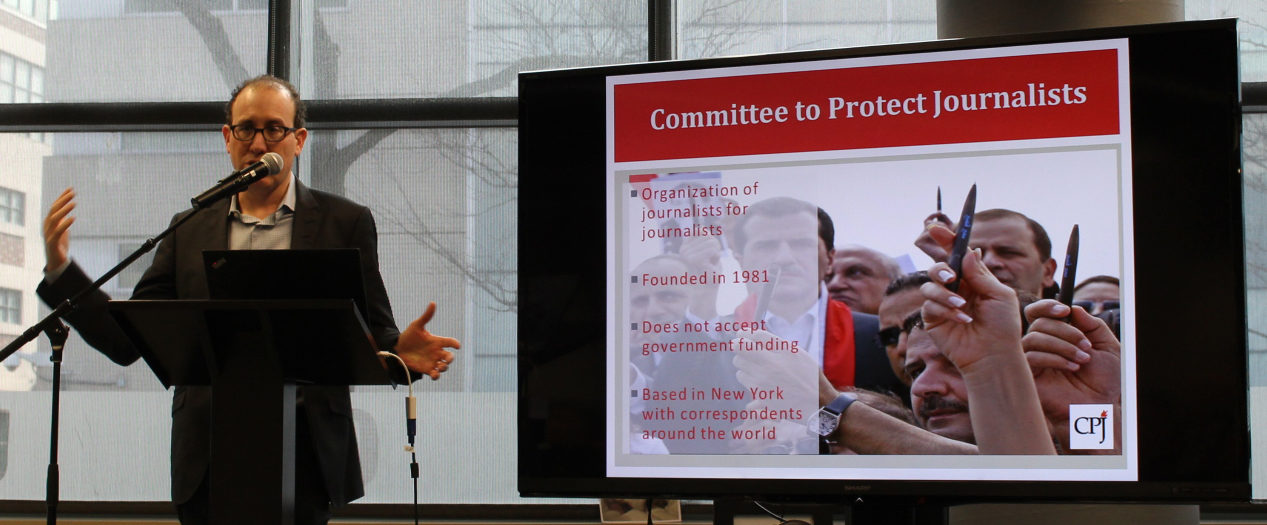

A record number of journalists are being killed or kidnapped because they have lost their bargaining power and are no longer the only way for radical groups to get their messages out, according to the executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

Journalists used to survive by pointing out that they were the best way for “violent forces” to communicate with a mass audience, Joel Simon said during a Jan. 15 presentation at the Ryerson University School of Journalism entitled “The New Censorship.”

“That’s what kept many journalists alive in many difficult situations.”

Simon, whose book The New Censorship: Inside the Global Battle for Media Freedom, was published last November, said there has been a “sustained” increase in the number of journalists killed since 2001, adding, “The last three years have been the most deadly and dangerous periods for journalists.”

According to the CPJ, the three deadliest countries for journalists are Iraq, Syria and the Philippines. In 2014, 221 journalists were imprisoned worldwide—also an increase from past years. Of those, 153 were staff reporters; the rest were freelancers.

“We live in an age defined by information, in which everyone has the ability to access tremendous information at their desk. This is unprecedented,” Simon told the 40 people who attended the event, including students, members of Canadian Journalists for Free Expression, Ryerson faculty and media lawyers.

“Yet more journalists are in prison around the world and press freedom is in decline. How can this be?”

[node:related]

In addition to losing their monopoly on reporting information, Simon said journalists are also falling victim to “democratators”—leaders that he defined as democratically elected, but who govern as dictators and authoritarians.

“Turkey, Russia and Venezuela are three countries with leaders that have genuine popular support, but once they get power, they govern in highly oppressive ways,” Simon said. “The media, as an independent institution, is marginalized.” Democratators imprison journalists and find other ways of communicating with the public, isolating the press even further, he said.

Parmis Mire, a youth counsellor at the Toronto Rape Crisis Centre, said she attended the event because, as an Iranian-Canadian, she is interested in surveillance issues and press freedom. “I’ve seen what my parents went through with censorship and the Iranian Revolution,” she said. “I think it’s important to learn about the government and media because, as Canadians, we’re raised in a protective way and we don’t feel the dangers of the international scene.”

During a question and answer period, Simon argued in favour of journalists’ right to publish—or not publish—the Charlie Hebdo cartoons. “Whether the material is grotesque or abhorrent, [journalists] must have a right to express it without any limitations. That’s what freedom of expression is,” he said. “We want the editors to decide, not gunmen or repressive governments. They have the right to [or] not to publish these cartoons.”

The event was hosted by the Ryerson Journalism Research Centre and visiting professor James Turk.

[[{“fid”:”3527″,”view_mode”:”default”,”fields”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:””},”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”attributes”:{“height”:”177″,”width”:”145″,”style”:”width: 82px; height: 100px; float: left; margin-left: 12px; margin-right: 12px;”,”class”:”media-element file-default”}}]]Sameera Raja is a fourth-year journalism student at Ryerson University. She is interested in digital media, foreign affairs and international journalism.