When Desmond Cole began writing a Toronto Life feature on the experience of being Black in Toronto, he thought he’d tell the stories of other people—until his editor suggested he tell his own.

[[{“fid”:”4286″,”view_mode”:”default”,”fields”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:””},”type”:”media”,”attributes”:{“style”:”width: 372px; height: 514px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px; float: right;”,”class”:”media-element file-default”},”link_text”:null}]]By Chantal Braganza, Associate Editor

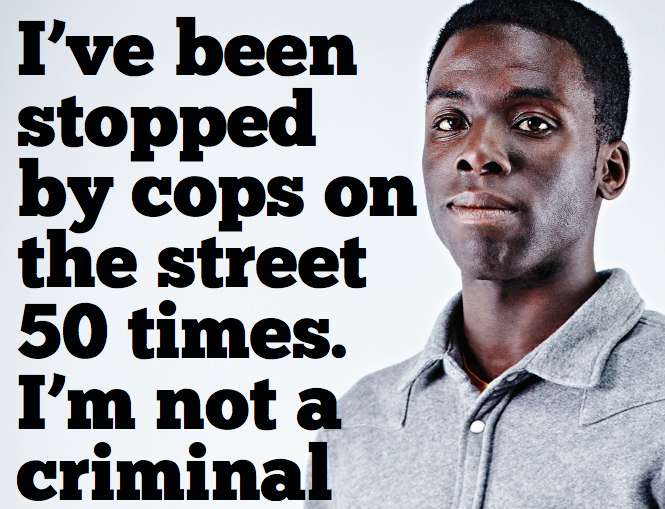

“I’ve been stopped by cops on the street 50 times. I’m not a criminal.” That’s the cover line of Toronto journalist Desmond Cole’s feature published in this month’s issue of Toronto Life. Cole’s first-person narrative about growing up Black in southwestern Ontario, interspersed with research on the Toronto Police Service’s practice of carding, has received enormous response over the past week.

We spoke with Cole yesterday about the challenge of writing your own story, city politics and talking about race in Toronto.

J-Source: Let’s start with process: did you pitch this to Toronto Life? Or did an editor get in touch with you to assign it?

Cole: A fellow named Mark Pupo, who’s no longer at Toronto Life, contacted me, and we met. He said he didn’t think that a feature about the Black experience in Toronto had really been written in quite some time. He was following my work and said believed I’d be a good person to talk about this.

When we first started talking, and he started giving me other examples, I was thinking originally about writing something that brought in the experiences of people in the community I knew. So I first started interviewing other people and getting their thoughts.

When I submitted that first draft to Mark, it wasn’t quite the draft they were looking for. Mark had actually left the magazine before I submitted that first draft, so Emily Landau was handling it.

The more that Emily got an idea about my own personal experiences, the more she became interested in me writing about that than me trying to do this big exploration of many different experiences. I’d never devoted a whole bunch of space to my own experiences.

J-Source: How did you feel about taking the feature in this new direction?

Cole: I felt a little bit shy, sharing my own experiences. I’m a journalist. I report on what other people are saying. That’s what I do, so that’s what my first instinct was. I thought about people I really admire and respect, so I went to them.

To be honest, until Emily started pushing it, I never thought about sharing my own experiences before.

J-Source: What do you think of the response to the story you’ve gotten so far?

Cole: It’s very exciting in one sense, because it’s something I feel very deeply. To see it get this much attention is validating. It gives me some hope that as a society, as a city, we can begin to move forward on some of these issues and change them.

I’ve been trying to use the coverage of this to talk about politics in Toronto. The politics in this city are really bad. We’re deferential to police power. We’re even more deferential to police power because as a city we’re willing to support carding.

I’m proud at least that I’ve been able to talk about the way people treat us in our own city—as if we have no rights.

This attention, as grateful as I am for it, doesn’t mean much if we can’t change things. Everything can’t change overnight, but there are certain things that can be done. Carding can be changed by the police and by the board if they make the decision to do so.

I have to tell you, though, I feel annoyed in some way. Because a story like this can get so big, and yet I see how little concern there is for the safety of racialized people in Toronto. It’s as if the city is trying to protect the rest of society from us.

So when I see people taking notice, I do ask myself: are they going to do anything now, or is it just being seen as a nice story?

J-Source: Former Toronto police chief Bill Blair mentioned your story on Metro Morning a few days ago, and said he’d read it. What did you think of his response?

Cole: I’ve lost all respect for Blair. I don’t have any respect for him any more, because he sacrificed a commitment to Toronto to salvage his own reputation. Nothing he really says to me has any credibility. What he essentially said is that he heard what I was talking about, and that he wasn’t going to do anything about it.

John Tory has said the same things: that he hears about kids who are terrorized by the act of police carding, admits carding is something that would never happen to his children, then votes in favour of it.

J-Source: One thing that comes out in your story is that you didn’t take a linear path to getting into journalism. When did you decide to start writing, and why?

Cole: I didn’t take a conventional path. I was blogging and writing my own things from time to time. And I had written about racial profiling and started publishing things in other places.

More than five years ago now, some folks at Torontoist, including David Topping and Hamutal Dotan, approached me and said, “We’d really like you to write for us.” I was really shy and didn’t think a whole lot of my writing. I usually wrote when I got angry—it was just kind of venting. So when they said they’d me to come and write for them, I didn’t really take them up on it.

Then I wrote a piece about how police were being introduced to our schools—something I thought was a terrible idea. Torontoist asked if they could reprint this. I was surprised, and then I thought maybe I should start doing this seriously.

It didn’t pay a lot and I wasn’t getting published anywhere else. I thought it would be a hobby or something I’d do from time to time. The years went on and I started writing more. About two and a half years ago, I started to quit the other things I was doing and did this full-time.

It was hard. I was very poor. I’ve been very poor most of the past three years. It’s only been in the last six months or so that I’ve been able to see a pathway towards this being a sustainable life. That’s with the addition with being able to appear on TV sometimes or radio.

J-Source: We’ve talked about the lack of diversity in Canadian bylines here before. Do you think working as a Black journalist in Toronto matters—either representationally or in the way people receive your work?

Cole: It matters because I have an anti-racist philosophy that I bring to my work. It doesn’t really matter what your ancestry is or what you look like if you don’t think that race is a factor in our everyday lives and is something that is still enough of a factor that it needs to be specifically addressed and combatted on an everyday basis. You could be a Black journalist in Toronto and still be another journalist.

But I’m intentional about bringing these issues to my work…that in my particular case has something to do with my experiences being a Black person growing up in Canada.

Our media doesn’t like to talk about racism. One of the interesting things about this piece is that it’s sparked a conversation about race that I haven’t seen in this city before. It’s often very hard to get everyone’s attention

Right now we have mass civil unrest in a place like Baltimore. Our tendency in Canada is to find the lowest bar and measure ourselves against that bar. We say, “Well, we’re not Baltimore, so why talk about this?”

J-Source: What would you say to other journalists starting out (or even not) who have story ideas that talk about race politics, but are hesitant to pursue them because of this reticence to talk about race in Canada, or a belief that people won’t care?

Cole: People do care. That’s the first thing. It’s so easy to validate the status quo if you tell yourself that people won’t care.

Toronto Life showed that if you put a picture of a Black person on their cover and say that this matters, that people will notice. It proved that a lot of people are interested in this. You have to give people who don’t usually have the opportunity to speak a chance to do so. That can seem challenging, but that’s what the whole exercise of journalism is supposed to be about.

J-Source: You’ve mentioned before that the response to your piece has sparked a conversation about race that you haven’t seen in Toronto. As these conversations open up, what would you like to see the city get out of them?

Cole: I can only just reinforce that it’s not enough for people to just understand, for example, that I’ve had some really bad experiences with racism and discrimination. We need to end it. We need to have it not be so much a factor in my life and in the lives of so many racialized people.

People who express concern about this need to act. Two things have happened since the piece was published that give me hope. One of them was when people would say, “Desmond, I’m sorry that this happened to you.” It meant a lot because it reached people on an emotional level. That’s what Emily, my editor, wanted. She said you have to show people your experiences. Don’t tell them.

The other thing I like was when people asked, “What can I do?” That ultimately is what journalism is supposed to be: a story that leads people to ask how you can change things for the better. I’m only hopeful that we can use this momentum of conversation—it’s good to start with a conversation—and use it towards positive reform.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Image courtesy Markian Lozowchuk.