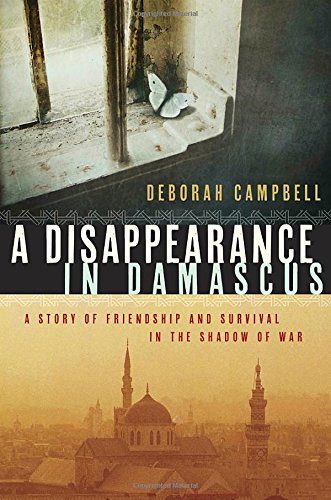

Deborah Campbell, A Disappearance in Damascus: A Story of Friendship and Survival in the Shadow of War. Knopf, 2016. 352 pages. $28.32.

By Jane Gerster

“Do you think anything you write will make a difference?”

A young Iraqi interpreter asks Deborah Campbell this early on in A Disappearance in Damascus: A Story of Friendship and Survival in the Shadow of War. That question, which Campbell returns to over and over again, is one of her most interesting in this book.

We meet Campbell in 2007: a veteran reporter standing on a Syrian highway, an immersion journalist en route to Damascus to report on Iraqis people fleeing to Syria following Saddam Hussein’s overthrow. Right away, she makes clear the type of journalism she is drawn to: intimate sketches of the people at the heart of intense conflict, the kind of work she did in her debut book, 2002’s This Heated Place: Encounters in the Promised Land.

It’s the style of reporting she intends to repeat here in Damascus, but then she meets Ahlam. Ahlam is a well-known Damascus fixer, a refugee from Iraq where her father educated her despite their community’s outrage and where she later survived being kidnapped. She invites Campbell to dinner in the apartment she shares with her husband and two children. Campbell apologizes for not covering her arms but Ahlam isn’t bothered. And although it’s not entirely clear at first what it is that binds Campbell so tightly to Ahlam – maybe it’s similarly unravelling relationships with their partners? – they soon become friends.

As journalism and friendship mix over a span of months and multiple trips back and forth between Syria and Canada, Campbell’s friendship with Ahlam forces her to contend with some significant truths about the nature of journalism, particularly foreign correspondence.

Fixers do much of the work that makes such reporting possible: they connect many journalists with sources they would not otherwise have access to and they take notable risks in the communities they live in, ones they can’t simply parachute in and out of like foreign correspondents. Campbell writes of being both pleased and embarrassed when Ahlam hugs her upon one return to Syria and cries in disbelief that she actually came back.

Ahlam is a fixer and friend, but also, Campbell begins to realize, one of the people she is reporting on. It is important to see journalists grappling publicly with the complexities, the ethics and the purpose of their jobs. Campbell’s candour here, especially as she begins to doubt the value of her work – “I began to fear that the recitation of memory only reopened wounds” – is a large part of what makes A Disappearance in Damascus an engaging read. Do journalistic intrusions hurt or help? Will anything change? Is there a point?

Campbell is like many reporters once swept up into a story: she feels an obligation to those she’s reporting on mixed with feelings of inadequacy and a sense of her own limitations, but also has financial considerations to make and family back home weighing on her mind. And then, right in front of her, Ahlam is taken.

The titular disappearance, which comes just after the halfway point in the book, serves as a testament to how gruelling yet bland investigative reporting often is. To find her friend, Campbell asks a lot of questions. She mines old contacts, she doubts and then attempts to verify what she knows and doesn’t know about Ahlam, and she shows up at offices repeatedly to push for answers.

As she hones all her reporting skills to find Ahlam, Campbell continues to struggle with journalism’s value. Ahlam once told her she worked as a fixer because “[s]omeone has to open the door and show the world what is happening.” But Campbell wonders, “Had I harboured, even in my moments of doubt, a grandiose belief in the power of story to alter destiny?”

At times Campbell’s choice of details feel untethered to the wider story and in some moments her prose feels stiff and academic. But for the most part, she is quite deft with ensuring that the necessary historical and political context does not overwhelm what is a compelling personal narrative.

[[{“fid”:”6784″,”view_mode”:”default”,”fields”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:””},”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”attributes”:{“height”:872,”width”:756,”style”:”width: 100px; height: 115px; margin-left: 5px; margin-right: 5px; float: left;”,”class”:”media-element file-default”}}]]Jane Gerster is a reporter with the Moose Jaw Times-Herald in Saskatchewan. She also freelances regularly, with stories appearing in The Wall Street Journal, VICE, The Toronto Star, and Daily Xtra.