By Christopher Waddell, Publisher

I have been a grocery shopper for about 40 years.

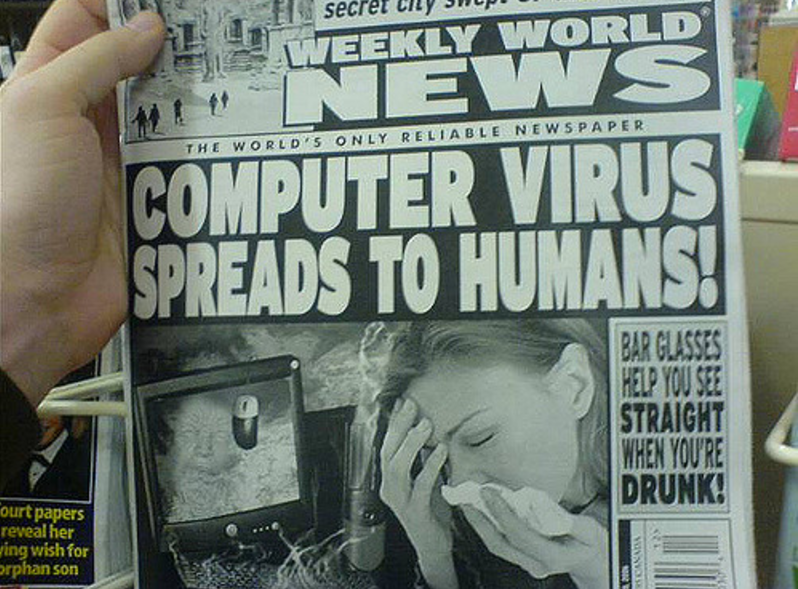

During that time in checkout lines I have read about cars that can run on water that the oil industry keeps secret from us, the pregnancies and affairs of hundreds of politicians and celebrities, regular UFO invasions of the earth hushed up by governments, the dead who come back to life and of course the capture by aliens of earthlings who return to tell their fantastic tales of the world beyond.

That doesn’t include the 38-under par score of 34, complete with five holes-in-one, recorded by Kim Jung-Il, North Korea’s dictator, in a round of golf in Pyongyang in 1994. Only under dispute is where he had ever played golf before that day.

Fake news has always been with us and people have always made money from it. What’s different today is speed — how quickly it can be distributed globally through social media and how fast that can be turned into cash by those who spread that fakery.

Of course there is also the fact that the whole term fake news has lost whatever meaning it once had (if it ever had any) by being used to describe factual news and information that politicians and other vested interests would rather not have made public. Making that information public is at the core of journalism’s role in society and democracy.

Craig Silverman of Buzzfeed has a simple definition of fake news — something that is published that is 100 per cent false. Whoever created it knows it’s false and that person or organization is making money from publishing it. That may disqualify golf news from North Korea, but is a pretty good description of the content of supermarket tabloids and many other publications in the pre-Internet world, just as it is of some online news today.

But before we get too carried away with the threat fake news is said to pose today, let’s get answers to a few questions.

Just because something may be distributed widely does that mean that people accept it as fact? Maybe they share it because it is clever, funny, bizarre or just a way to waste time at work or home.

Do we really think Donald Trump won the presidential election in the United States because stories were circulated saying Pope Francis endorsed him? Or that Hillary Clinton lost because of rumours she had health problems or ran a sex business from a pizza shop?

One of the toughest things to determine is why people vote the way they do. Lots of people may pronounce on the issue but no one really knows. There are almost as many reasons as there are voters. It’s the political equivalent of the people who tell you authoritatively why the stock market went up or down that day. Mostly they don’t know.

We do know that people see fake news primarily through social media. But again the key question is not do they receive it but do they believe it?

In Canada there is some evidence that they don’t.

Public opinion research done by Allan Gregg and the Earnscliffe Strategy Group, supported by the Canadian Journalism Foundation (where I chair its research committee) for the Public Policy Forum’s Shattered Mirror report on the state of media in Canada touches on the question with usual research caveats. It was just one online public opinion survey of 1,509 Canadians in late September-early October 2016. But it produced interesting findings related to fake news and the state of news media more generally, that warrant asking Canadians more questions.

It asked, “Would you say you completely trust, mostly trust, partially trust or do not trust the news that is…?” on television, radio, newspapers and magazines and the online sites of newspapers and magazines. It found 65 to70 per cent of respondents completely or mostly trusted news from each of those sources.

For digital sites like Huffington Post and Reddit that fell to 34 per cent, for news received by email that fell to 17 per cent.

Social media was at the bottom of the trustworthy list. Only 15 per cent completely or mostly trusted news on social media and, perhaps surprisingly, only 13 per cent completely or mostly trusted news sent to them by friends on social media.

In another question, 83 per cent of respondents agreed with the statement “a lot of bogus and untrue information appears online.”

In the United States there has been 50 years of political polarization and vilification of the media that goes back to Richard Nixon’s silent majority and Spiro Agnew’s description of the media as “nattering nabobs of negativism”.

The situation there may well be different but the U.S. is not Canada. Here attempts to replicate the U.S. by polarizing politics have failed (Kellie Leitch, the niqab ban at citizenship ceremonies and barbaric cultural practices snitch lines) as have attempts to polarize the media (Sun News on television). Most people simply weren’t interested.

The role of a national public broadcaster, particularly on radio where it is the most listened-to station in many urban centres, may also be influential as a trusted news and information source in public perceptions of media accuracy as well as setting a standard for private media.

It’s convenient in the U.S. for many to focus on fake news in the context of the presidential election. That may deflect attention from posing other more difficult questions for the media and the political class, such as why the two major parties couldn’t find candidates who were younger than 69 and 70 —and the outsider who galvanized many was 74) — the failure of the Democrats’ campaign, or the the takeover of the Republican party by someone unsuitable in every way to be president let alone lead that party.

Or they could ask why the media spent so much time covering the candidates and so little time covering the voters and whether Facebook, Google and other social media sites are technology companies or news organizations with responsibilities to audiences and the general public to oversee content.

The assumption that underlies a lot of the concern about fake news appears to be that much of the public is stupid and gullible, that the public is mesmerized into doing things that they are too foolish to realize are against their best interests or that, particularly if it is sent by their friends, voters fall for whatever they see and read.

More detailed research is needed to find out just what Canadians actually believe is true on social media. For fake news at the supermarket checkout the answer has always been not much and there’s some evidence in Canada at least that in the digital era that really hasn’t changed.

Christopher Waddell is a professor at the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University. He can be reached at publisher@j-source.ca.