As local community and daily newspapers close across the country, their archives – and their stories of local politics, controversy and culture – are at risk.

“Community newspapers tell us a story of time and experience,” said Claire Gilbert, an archivist and librarian at the Royal British Columbia Museum.

“They’ve got everything from the way we advertise products and services to editorials on timely social, political and economic issues. They really are an important commentary on life…But because a lot of newspapers are run as businesses, they don’t always reach out to an archive or a community group to take their records. I think it’s important that we pay attention now because we could risk losing the smaller, regional voice.”

The Local News Map, an online crowd-sourced map tracking changes in the availability of local news in communities across Canada, has documented about 207 local community and daily newspapers that have closed in 160 communities since 2008.

“Community newspapers are an invaluable tool for the public, for academics and for journalists, as are their archives,” said April Lindgren, the map’s co-creator and principal investigator for the Local News Research Project at Ryerson University’s School of Journalism.

“We often go back and look at, for instance, what politicians said in the past and what was said during a debate in order to hold power accountable in the future or to understand why the present is the way it is.”

Once a newspaper folds, its online presence usually follows suit.

Such was the case for What’s Up Muskoka, a community newspaper published in Ontario’s Muskoka region that was closed in January 2016 by its owner Postmedia Network Inc. The websites of both the newspaper and its sister news publication, Muskoka Magazine, have since been shuttered. And while physical print copies of What’s Up Muskoka can be found in the Bracebridge Public Library, its lack of online archive makes it difficult for anyone who does not live in the area to access.

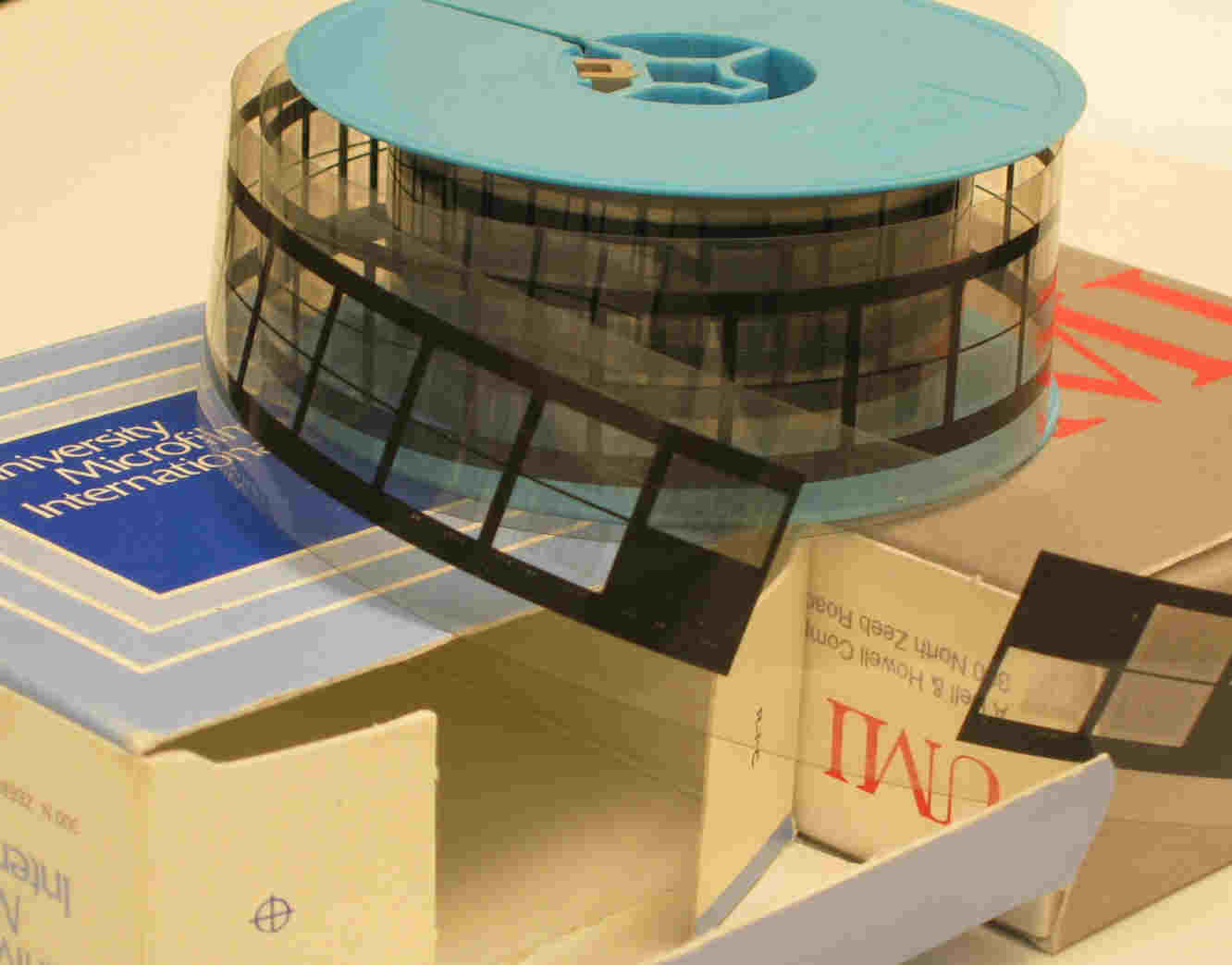

The Moose Jaw Times-Herald, a 128-year-old Saskatchewan newspaper owned by Star News Publishing Inc., published its final print edition Dec. 7 and shuttered its website shortly after. The Moose Jaw Public library has expressed interest in preserving the paper’s archives, the paper’s publisher told a CBC reporter. These archives include paper and microfiche copies dating back to the Second World War.

“If (a newspaper archive) is in the form of a physically printed and purchased paper that is on newsprint, then you have the long-term consideration that it is on very acidic, brittle paper. The original newsprint is very fragile for long-term storage,” said Gilbert. Preserving newspapers on microfilm is best, she explained, and digitizing the microfilm can make it easily accessible to researchers.

Unfortunately, these methods of preservation can prove too costly for many small-town libraries and museums.

“I don’t think there’s any archive or library in Canada that would refuse (physical copies of a newspaper), but the considerations we have, of course, are the costs associated,” said Gilbert.

“None of us operate with deep pockets these days, and so while we would absolutely consider it a part of our responsibilities, there is just an enormous cost associated. As cultural institutions we don’t necessarily have the budgets to be able to do this for every newspaper.”

Concerns over the preservation of closed newspapers’ archives came to light most recently after a publication swap between media companies Postmedia and Torstar Corp. in late November. The transaction led to the closure of over 30 community and daily newspapers, mostly in Ontario. The folded papers’ websites began to disappear a few hours after their closures were announced, most redirecting readers to the site of the closest newspaper owned by the purchasing company.

For example, readers searching for an old story on the websites of the Kingston Heritage or the Frontenac Gazette, two Ontario community newspapers bought and subsequently closed by Postmedia, are now rerouted to The Kingston Whig-Standard, which is also owned by Postmedia.

Reporter Emma Jackson was on maternity leave when she found out that the daily paper she’d worked for, Metro Ottawa, had been traded from Torstar to Postmedia and would close immediately. She also learned that the paper’s website would disappear, along with its archive of articles she’d written in her two years as the paper’s transit and transportation reporter.

“I went into mad scramble mode to save my articles,” she says. “I didn’t keep physical copies of the paper because that’s just not practical, and I assumed that these articles would just stay on the Internet.”

When Postmedia and Torstar bought each other’s newspapers, they also acquired the archives. A spokesperson for Torstar said that the media company plans to import articles from the newspapers it bought and closed and place them on their other publications websites. A spokesperson for Postmedia said the company won’t import the online archives of the newspapers it bought and closed onto its news sites, although some articles from the defunct papers will still be available for purchase online through companies like Infomart and ProQuest.

For now, Jackson’s articles can still be found on Metro Toronto, although she worries that they are not easily accessible to the public and may disappear altogether.

“For the public, they have to know very precisely what they are looking for in order to find them. The average person looking for context surrounding an issue is now not going to come across those articles. They’re too deeply buried,” she says.

Both Torstar and Postmedia said they are open to donating the physical print copies of the papers they bought and closed to libraries, universities, museums and other organizations, but neither company gave a firm plan on how they’re going to do this.

“Understanding our present means being able to read about our past,” said Lindgren. “If we don’t have these archives or access to old newspapers as researchers, historians and citizens, it really compromises our ability to understand why things are as they are right now.”