There are fewer journalists in Canada than 15 years ago — but not as few as you might think

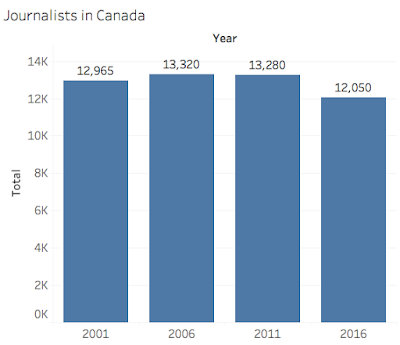

There are fewer journalists in Canada today than 15 years ago — but not as few as you might think, according to data from the 2016 census, the most recent and comprehensive data available.

Indeed, between 2001 and 2016 — a time of mass layoffs at daily newspapers across the country — the total number of journalists in the country declined by only 7 percent.

As the chart above shows, there were just under 13,000 journalists in Canada in 2001. That number went up to 13,320 in 2006, stayed relatively flat in 2011, then dropped a bit in 2016.

Over the whole period, the decline was just 7 percent. And even if you measure the decline from the very top — the 13,320 journalists recorded in 2006 — the number of journalists is down by just 10 percent.

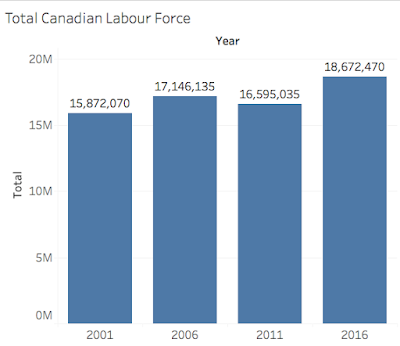

But absolute figures can be a bit misleading. The size of the overall labour force in Canada has risen 18 percent since 2001, so the relative decline in journalists is greater than it might first appear. Indeed, as a proportion of all working Canadians, the relative share of journalists is down by 20 per cent.

Still, when people talk about how much smaller newsrooms are today than a decade ago, they’re usually talking in absolute terms: They look around at cubicles and count heads.

But, before we go any further, it’s important to make note of one important thing: What Statistics Canada considers a “Journalist” and what they don’t.

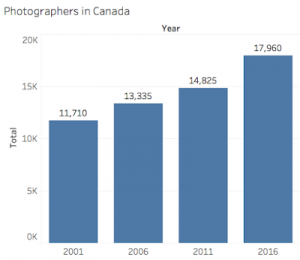

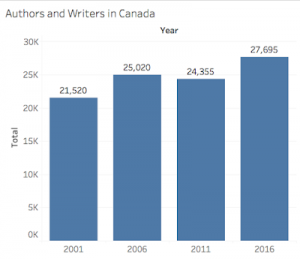

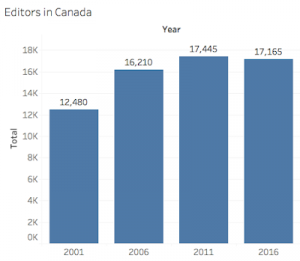

The way StatsCan defines “Journalist” specifically excludes two groups that most people would consider journalists: photojournalists and editors (they’re instead lumped in with the broader categories for “Photographers” and “Editors”).

The bottom line, though, is that it may be more helpful to think of the “Journalist” numbers as really just showing us the numbers for “Reporters” or other journalists whose main job is writing: columnists, critics, etc.

Even viewed in that limited way, though, the numbers are surprising. Ask anyone working at a newspaper, radio or TV station how many reporters they’ve lost in their newsroom over the past 15 years and I doubt many would say it’s only 10 per cent.

So what’s going on?

Let’s start with the obvious: Journalists are losing their jobs.

Annual layoffs and buyouts have been a fact of life at newspapers across the country for at least a decade. I took a buyout from The Vancouver Sun in September 2015, and when I left, that paper’s newsroom was a fraction of its size when I joined it in 1998.

Last year’s Shattered Mirror report into the state of Canadian journalism came up with some sobering estimates based on data from unions (emphasis added):

The Canadian Media Guild has tracked layoffs and buyouts for the past few decades. When non-news companies are excluded, the total is in the order of 12,000 positions lost, more than 1,000 of them in the last year alone. Unifor’s 46 media bargaining units had 1,583 members in 2010 but only 1,125 by early 2016. The CWA estimates it had about 400 editorial members in 2016, a decline of about one-third from 2010 and more than two-thirds since the early 1990s.

Unifor Local 2000 — which represents various newspaper employees in B.C., including those at The Vancouver Sun and Province — told me their membership has dropped from around 2,300 in 2010 to just 800 today (a drop of more than two-thirds).

Some of those union figures include people who work for news companies but aren’t journalists, like those working in circulation or advertising. Still, these figures suggest mainstream newsrooms may have seen job losses in the order of 30 per cent or more in just the past few years.

If that’s true, that means there’s only one way to explain an overall drop in journalists of just 10 percent.

Someone has to be hiring journalists. And some are.

At the same time as Google and Facebook have gobbled up ad revenue that used to go to newspapers, the internet has also made it easier to create new media outlets and for niche publications to find an audience.

There are several news organizations in Canada today that didn’t even exist 15 years ago, like iPolitics, The Tyee, Discourse, National Observer and Canadaland. Each has its own unique business model: grant funding, subscriptions or donations.

Here in B.C., Castanet, a very successful online-only news site in the Okanagan, has 13 reporters and editors. Metro, the free weekly, has plans to hire a bunch of reporters in Vancouver. And, after a rather brutal round of consolidation and closures, it appears some community papers in the Lower Mainland have started hiring journalists again.

There are also all sorts of niche publications that, while small, do employ actual journalists. Like Modern Dog magazine (based in Vancouver) or The Growler, a quarterly magazine all about B.C. craft beer.

An increase in funding to the CBC hasn’t hurt either, with many ex-newspaper employees now doing stellar reporting for the public broadcaster.

The good news doesn’t completely outweigh the bad, of course (indeed, statistically, it falls short by about 10 percent). But there is good news out there. It just tends to come in lots of small doses that may go unnoticed when compared to the big layoffs at big newsrooms.

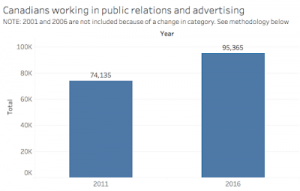

Because at the same time as journalism jobs have declined slightly, jobs that require similar skills — like public relations and photography — have grown substantially.

Indeed, for every job lost in journalism since 2011, there have been 17 jobs added in public relations and advertising (-1,230 vs. +21,320).

That’s probably not great for democracy — I’d rather have more watchdogs than spin doctors — but it should soften the blow for journalism students looking for work.

The surge in jobs in related fields like PR should also be good news for journalists who have been laid off (or fear being laid off): Rest assured, there’s ample demand out there for your research and writing skills.

I still think we should worry about the decline of newspapers, and other “legacy” news organizations, which serve an important role in democracy.

But these figures at least give me some hope that it’s not all bad news in the news business. And that there’s at least a chance that new business models will help us figure out a way for journalists to continue to do important work in our communities.

This story was originally published on Chad Skelton’s blog. It has been edited for length and republished with the author’s permission.