This series was funded by readers like you through donations to the J-Source Patreon and FutureFunder at Carleton University.

In the summer of 2018, Angela Long embarked on a 22,000-kilometre journey, traversing eight provinces and a territory – from Dawson City, Yukon, to Cape Breton, N.S. – to learn from residents, reporters and experts about journalism’s importance in rural markets. In this series, she tells the stories of local news survivors and the roles they play in bolstering their communities.

The first thing Dennis Smyk did was apologize. “My voice is low,” he said, “because of all the radiation.”

The 73-year old co-owner of the Ignace Driftwood explained how a decade ago he was diagnosed with prostate cancer, and how just last winter he was given weeks to live. Months later, the sound of a July rain backdropped his voice. He struggled to get comfortable in his green swivel rocker, a handmade quilt draped on its back. “No,” he said to an offer to cancel our interview. “This is important.”

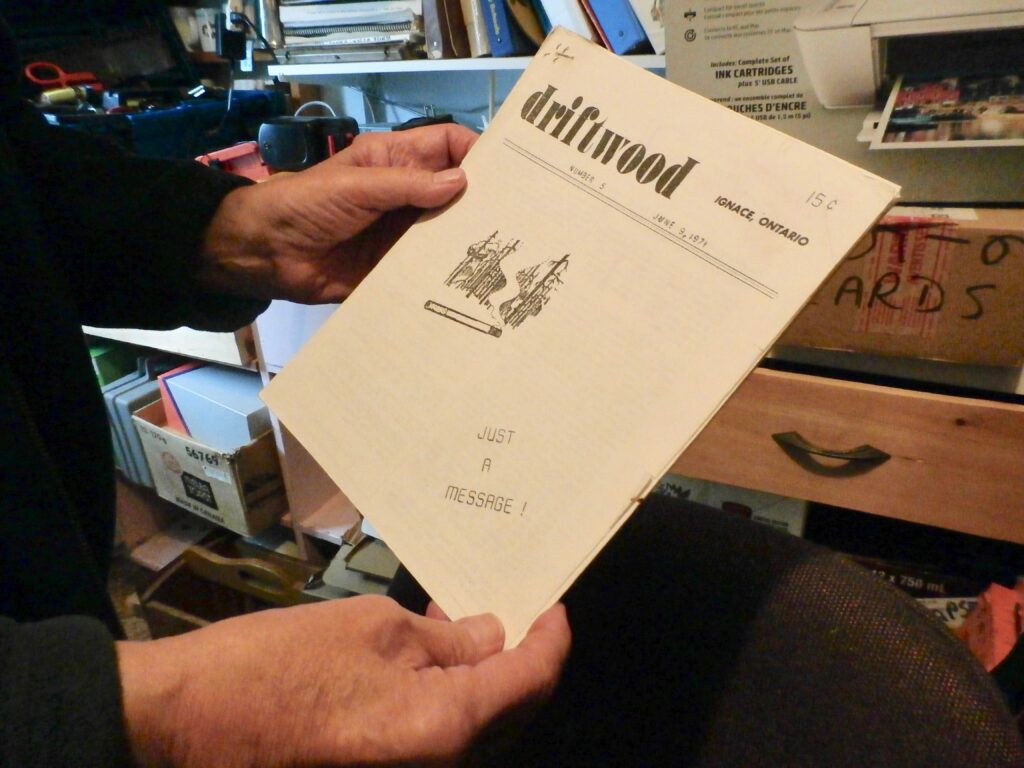

The Ignace Driftwood had been important to Smyk since he and his wife and business partner Jackie published its first issue on a Gestetner in 1971. So important that through a decade of chemotherapy treatments and chronic debilitating pain, Smyk had never missed an issue. Before he got a laptop, his son would bring Smyk’s desktop to the Thunder Bay hospital where he was receiving treatments so he could work. “I never realized how heavy that thing was,” said Smyk, “until I tried to carry it home.”

On Oct. 31, 2018, Smyk published the final issue of the Driftwood. One week later, he died.

While the Driftwood’s circulation was just over 300 and Ignace’s population hovers around 1,200, media outlets such as CBC Thunder Bay and the Dryden Observer paid tribute to Smyk’s life. Dozens of locals and politicians, including Kenora MP Bob Nault, expressed their condolences.

But Smyk left this world with the fate of the Driftwood in limbo. After a few promising bites, no one has stepped forward to continue publishing the paper, which hadn’t missed an issue in four decades.

“There’s nothing sadder than a town without a newspaper”

While researchers continue to analyze reasons for newspaper closures across North America – corporate mergers, shifts to online and free news, the decimation of traditional advertising models – sometimes there’s a simple reason. An owner dies and there is no one to take their place. And when a paper dies in a town of around 1,200 in northern Ontario where it takes an hour driving along the Trans-Canada Highway to get anywhere, some say the voice of the entire community dies with it.

The subject of death comes up often in rural journalism. In a 2016 interview with the owner of the Fort Frances Times, a community 224 kilometres southwest of Ignace, Jim Cumming, who was 66 years old at the time and had no children interested in taking the reins, worried about the future of his more than 120-year old paper. Despite flood, snowstorm, power outage, the paper had never missed an issue. But something so simple as his death, he said, could change all that.

“I worry about small papers in rural Canada,” Cumming said, “their ability to continue to exist to be the glue of the communities.” He wondered if anything would be there to replace them. “You’ll be able to see it,” he said. “I won’t.”

Chad Stebbins, executive director of the International Society of Weekly Newspaper Editors, an organization based out of Missouri Southern State University with more than 313 members (including 27 Canadians), also worried about small-town papers. He worried about members growing older, those in their late 60s and early 70s who were ready to retire but not ready to sell to a chain.

“They’d like to find a local buyer, someone who can carry on the tradition of a quality newspaper, but often it’s difficult finding someone who wants to work that hard,” he said during a 2017 phone interview.

Stebbins pointed to the Hardwick Gazette’s 71-year old owner, Ross Connelly, who had resorted to an essay contest in the summer of 2016 to find a new owner for the then 127-year old Vermont paper. Due to a lack of entries, Connelly turned to a Kickstarter campaign. Finally, nearly a year later, one of the original essay writers stepped forward to purchase the paper.

“There is nothing sadder than a town without a newspaper. It’s the glue of the community,” Stebbins said. “What happens to a community when it loses its newspaper? Who fills the information void?”

The local paper – an ‘all-in-one’ package

Nearly six months since Smyk’s death, these are exactly the types of questions the residents of Ignace are asking.

“There has not been one place yet to fill that void,” said recently retired business owner Karen Greaves in a March 2019 phone interview. While there have been efforts to disseminate community information through the Ignace Area Business Association, the Facebook-based Ignace Discussion Group and Ignace Classifieds, and more old-fashioned methods like posting on bulletin boards or calling house-to-house, Greaves worries people are missing events.

“In the Driftwood, events weren’t just in a bubble and nobody knew about them,” she said.

Information, which can get lost in an ever-changing stream of Facebook feeds, said Greaves, can be inaccessible to seniors. Seniors, about a quarter of the population, don’t all have computers. Bulletin boards and phone calls also don’t guarantee residents will be informed. Having an “all-in-one” package for everything – the newspaper – was something Ignace just took for granted, she said.

But the void left by the paper can mean much more than just missing a few events, said Greaves, who subscribed for 33 years.

“We could take pride in the paper,” she said, “and I think that’s what it really fostered, pride in the community for all ages – from preschool to seniors – everything was covered.”

Linda McIntosh, a former cabinet minister from Manitoba who retired in Ignace in 2004, is also missing the Driftwood.

“It was a holy little thing somehow,” she said in a March 2019 phone interview. “It wasn’t big and it wasn’t really fancy, but the photographs, the articles, and the covering of events in a little town like ours … “

McIntosh said she’s already missed hearing about some events – a tea hosted by the Silver Tops Senior centre, a snowmobile derby on Agimak Lake. She talked about the kinds of stories Smyk would cover that had the power to change locals’ perspectives. The story of Joe Roberts comes to mind, she said, the 44-year old who walked nearly 9,000 kilometres across Canada in 2017 pushing a shopping cart to raise awareness for youth homelessness.

“If it weren’t for Dennis,” McIntosh said, “that guy would have just kind of walked through town.”

As a former politician, she spoke of the importance of letters to the editor and political engagement. In a town in the midst of economic transition, one of the Nuclear Waste Management Organization’s five remaining contenders for a nuclear waste repository, the Driftwood provided a forum for community debate.

The death of Dennis Smyk, however, means more than the death of the local paper, said McIntosh. It’s something much more personal.

“It’s like one of the family members has left home, left a gap,” she said. “The paper was a vehicle for communication, but it was almost like a glue that kind of helped keep the family intact.”

A paper without a home

At home on Balsam Street, which doubled as the Driftwood’s office, Jackie Smyk, Driftwood co-owner and Dennis Smyk’s wife of 48 years, is feeling that gap more than anyone.

“I’m still in mourning,” she said in a March 2019 phone interview.

She did everything “you couldn’t see” at the Driftwood, Smyk said – bookkeeping, billings, “basically just being an office person.” Occasionally she would also report stories and write editorials. She said she misses this life “like crazy” and struggles to fill days once filled with the ringing of the phone and the buzz of living with the town reporter. She knits, she quilts. She hopes that someone will call one day and offer to buy the paper. She remembered Dennis sitting in his chair after he finished the Oct. 31 issue, so weak and shaky.

“‘I just can’t do this anymore,’ he said, ‘this has to be the last issue,'” Smyk recalled. “He was heartbroken.” There’s a long pause on the other end of the line. “I’m trying not to cry.”

Beyond the pit stop

Back in July, birdsong started up as the rain stopped. Dennis Smyk started to cough. “That’s the sad part,” he said after clearing his throat, “no one is interested in taking it over.”

He reminisced about a career spent covering the stories of a place that at first glance “looks boring,” he said, nothing but a pit stop along the Trans-Canada highway. But what people don’t see is what awaits them off the beaten track.

“I don’t fish. I don’t hunt. I just explore,” Smyk said of his canoe trips throughout these lands, where, as a licensed avocational archaeologist, he had documented more than 600 archaeological sites and 150 pictographs.

He cherished writing about such explorations in the Driftwood, and also about the history of the town where his father settled in the early 1930s after leaving Poland. “He did the usual things,” said Smyk, “railway in the summer, bush worker in the winter.”

Smyk was a firm believer in history. “It’s important to recognize people in the community, and who they were, and what they did,” he said.

After more than an hour of talking, Smyk scarcely acknowledges what he did. These things are discovered months later. Ignace’s museum was named after Smyk in 2018 – the Dennis Smyk Heritage Centre. A pictograph site featuring a rare multi-coloured image – the Smyk Site – pays tribute to his archaeological contributions. In 2013, he received the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal for more than 50 years of volunteer service in northwestern Ontario. At one point or another, he served as mayor of Ignace, as councillor, as volunteer firefighter, as fire chief. Since his death, a plaque at Ignace Public Library recognizes Smyk for his contributions to the community.

With such a large presence in his community, Smyk’s vision of a small-town newspaper followed suit. This was cemented, he said, when he attended a conference several years ago.”‘What do you want, is it a newspaper or a yearbook?’” he recalled a speaker saying, “and he meant it with all sincerity. I’ve been thinking about it.”

“We are a yearbook,” he said. “Yes, it’s news, but I can look back at our paper for over forty years and say ‘This is what happened then.'”

When asked what he felt his role was as a newspaper publisher in rural Canada, Smyk struggled to get out of his chair.

“Well, I was supposed to be dead so they had a surprise party for me,” he walked out of the room, returning a few moments later with an off-white sash, unraveling it across his chest. Red letters spelling Mr. Ignace were sewn onto the fabric. “So, I guess that’s my role,” he said.

Smyk didn’t sit back down. “I suppose you want to see my office,” he said.

Quilted placemats and wall hangings marked with vibrant colours and scenes of nature decorated the living room and kitchen. Houseplants filled every blank space of the pine-clad rooms. Photographs of all sizes – a little boy on the beach, a little girl on Santa’s lap, black-and-white wedding photos, a young man wearing a graduation cap, birthday cakes alight with candles – plastered the hallway walls.

“There are so many memories here,” Smyk said, opening the door to his office. “It’s cramped,” he said of shelves filled with books, a calculator, a wooden carving shaped like a bunny, a Heritage Ontario poster, VHS tapes, two Mac computers, “but it’s cozy.”

What Smyk wanted to show me more than anything else were his photos of pictographs. One in particular, that of a red-ochre handprint on a mottled-grey rock, fascinated him. ”I think that might be a sacred spot, where the Maymaygwayshi live,” he said of the beings who live along shorelines in crevices in cliffs, stories he’d learned from First Nation elders. “They say the handprint marks a gateway to another world.”

Smyk asked the time. He’d heard Science North’s Science En Route outreach program was in town today, at the library, and he promised the librarian he’d cover it. Yes, he had time for one or two photos outside the house in front of the Driftwood sign, but then he’d have to go.

Smyk stretched out his hand, gently touching the wooden sign. He gathered up his notebook and camera, opened his silver van door, and waved goodbye.

Editor’s note: This story was updated at 1:15 p.m. ET to clarify Jackie Smyk’s role with the Driftwood.