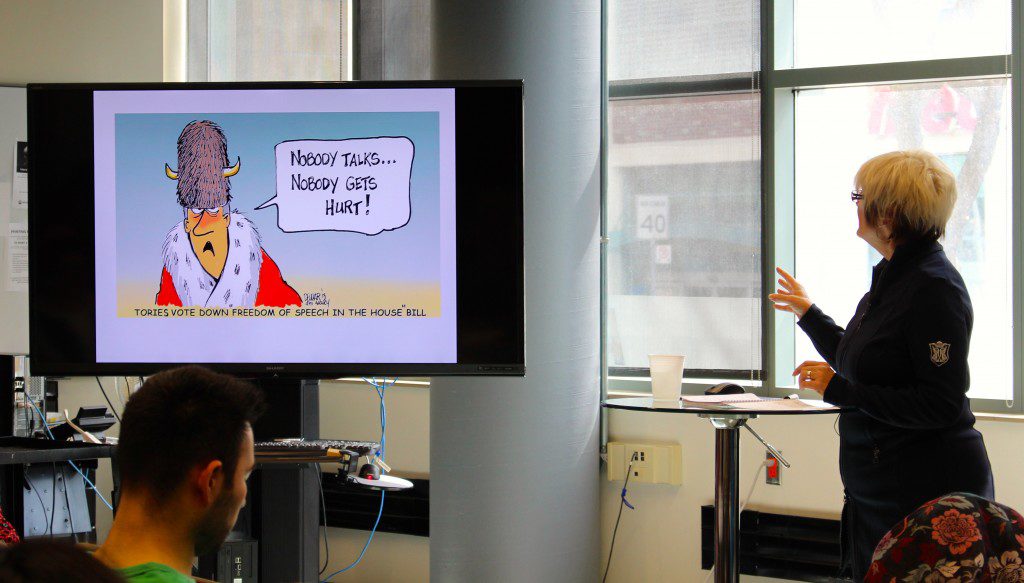

Cartooning is not for the faint of heart, Sue Dewar told attendees at the 2015 Atkinson lecture at the Ryerson University School of Journalism.

[[{“fid”:”4135″,”view_mode”:”default”,”fields”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:””},”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”attributes”:{“height”:”583″,”width”:”1024″,”style”:”width: 400px; height: 228px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px; float: right;”,”class”:”media-element file-default”}}]]By Lindsay Fitzgerald, for the Ryerson Journalism Research Centre

Sue Dewar’s “trial by fire” was a 1995 cartoon of a beaver gnawing on the prosthetic leg of Bloc Québécois leader Lucien Bouchard. The cartoon, published after sovereigntists lost Quebec’s referendum vote, resulted in more than 6,000 death threats against the Toronto Sun editorial cartoonist. In the House of Commons the cartoon was condemned by all parties, while Bloc members sat with her cartoon on their lap as a form of protest.

Cartooning is not for the faint of heart, Dewar told more than 100 students, faculty and members of the public gathered to hear her deliver the 2015 Atkinson lecture at the Ryerson University School of Journalism.

“You have to have the courage of your convictions with your drawings.”

Dewar, in a speech entitled “Colouring outside the lines,” said that despite Canada’s freedom of speech guarantees and tolerance of dissent, there are subjects she is wary of drawing. Nudity, for instance, is a no-no and she says she would not draw Muhammad without a pressing reason.

Dewar, whose cartoons appear across the country in Sun newspapers, paused occasionally to draw images of politicians she loved to torment over the years. For Brian Mulroney, every time he “put his foot in his mouth I’d draw a bigger chin,” she explained, laughing as she recreated the former prime minister’s cartoon image on a whiteboard. In the case of former Ontario Premier Dalton McGuinty, she extended his nose every time he fibbed. And Dewar began adding a toilet paper roll onto Harper’s headgear after a press release from his office spelled Iqaluit as Iqualuit in a press release. When it’s spelled correctly, it means “plenty of fish;” when it’s spelled incorrrectly it means people who don’t wipe their bums.

On a more serious note, Dewar outlined the extent to which cartooning was a high-risk business in many countries even prior to the January 2015 Charlie Hebdo attacks, which provoked widespread debate over the power of political cartoons and limits to free speech.

While there are few women who work full-time at newspapers as editorial cartoonists, Dewar said the internet makes it possible for a growing number of female cartoonists to get their messages out. Many of them are paying a high priced for their satirical commentary. Among them are:

Iranian artist Atena Farghadani who has been on a hunger strike in a Tehran prison since February to protest her incarceration for a cartoon that allegedly depicted members of parliament as apes. She was protesting against the government’s attempt to restrict access to contraception.

Palestinian cartoonist Majda Shaheen, who has received constant death threats for the cartoons she publishes on her Facebook page that criticize the military strikes in Yemen. There was also a major online campaign mounted against Shaheen to stop her from cartooning because her drawings were critical of Hamas. In 2014, Shaheen was the co-recipient of Cartoonists Rights Network International’s (CNIE) Courage Award.

Egyptian cartoonist Doaa El Adl, who is well known for speaking out against political parties. She was charged in 2012 with blasphemy for a cartoon published by the independent Egyptian newspaper Al Masry Al Youm. Though El Adl is constantly under threat, she told the online magazine Sampsonia Way that “these strong reactions to the cartoon is a good thing, whether the reaction is acceptance or rejection.” She added that the challenge of being a female cartoonist in a male-dominated industry has only made her “determined to carry on.”

Molly Norris, a cartoonist with the Seattle Weekly, who was placed on Al Qaeda’s “hit list” in 2010 after depicting Muhammad and launching an “everyone draw Muhammad” day. Since then, she has received FBI protection because she has been the target of so many death threats.

Kanika Mishra from India, another 2014 CNIE Courage award, who is known for her criticism of Asaram Bapu, a high-profile religious leader in India accused of rape. Despite many death threats against her, she continues cartooning to bring attention to the widespread problem of rape in that country.

Arwa Moukbel from Yemen, who is unable to cartoon about anything social or political in her own country, but distributes cartoons criticizing the military actions by the Saudi Arabian regime on Facebook.

Dewar said cartoonists are driven by the opportunity to “make some kind of contribution towards change.”

“These [cartoons] are necessary – we do these to keep the people in power at bay,” she observed. “And you can see what happens if you do that in a country where you can’t do that.”

In Canada, the Association For Canadian Editorial Cartoonists (ACEC) has historically brought together cartoonists from various mediums across the country. Dewar, a previous head of the association, says Toronto will be the host of a spring international gathering of cartoonists that coincides with Comic-Con Festival 2016. The goal of the meeting, she said, is to bring cartoonists from around the world into one society.

Lindsay Fitzgerald is a fourth-year student in the Ryerson University School of Journalism.

Illustration photo by Robert Liwanag.

This article originally appeared on the RJRC’s website, and is reprinted with permission here.