Many of us get our daily news from the internet. Running the gamut from real to fake to satire that is “proudly fake,” online news outlets gather and present stories for their readers.

While we may think there has never been a news era like this before, these “newsfeeds” are strikingly similar to newspapers in the early 1800s. We can learn a lot by seeing how things worked two centuries ago. We might even learn some lessons on how to help today’s news.

In my research, I looked at newspapers and society in the 1800s. I focused on papers published roughly between 1830 and 1840 in Lower Canada (Québec), Upper Canada (Ontario) and the United States from Vermont to Michigan. I was trying to learn how radical reform ideas were spread by these papers.

In the process, I also learned a lot about the newspaper business from the era: Who wrote for these papers? Where did they get their information? Who read them?

With the current closing and shrinking of local news, the rise of “fake news,” and the inability of traditional media outlets to make money in the digital age, we can draw lessons from the past to help us discuss the problems facing journalism today.

Old newspapers were like blogs

The newspapers I studied were usually around four pages. Most of them were published a few times each week, some less frequently. A select few were the first daily newspaper in their region.

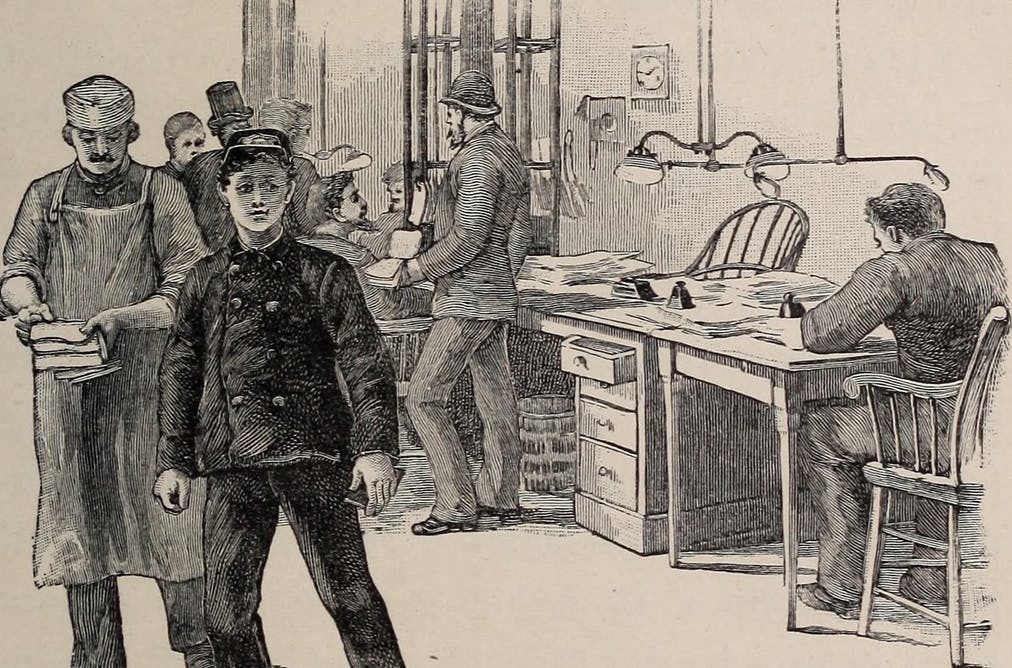

Many of the newspapers were similar to today’s blogs: Instead of drawing on skilled reporters, papers were produced by one or two people who often had other jobs or sources of income. One editor was also a public notary, another was a doctor and a third made money giving lectures.

Newspaper editors would copy, crib and comment on articles their peers had written. Instead of offering full and objective coverage of current issues, papers reflected the interests and politics of their owners and editors — who were, in many cases, the same person.

Most of these papers constantly struggled to make money. In an era before newspaper boxes, papers would be passed from family to family. As a result, many people would read every issue of a paper without ever paying for it.

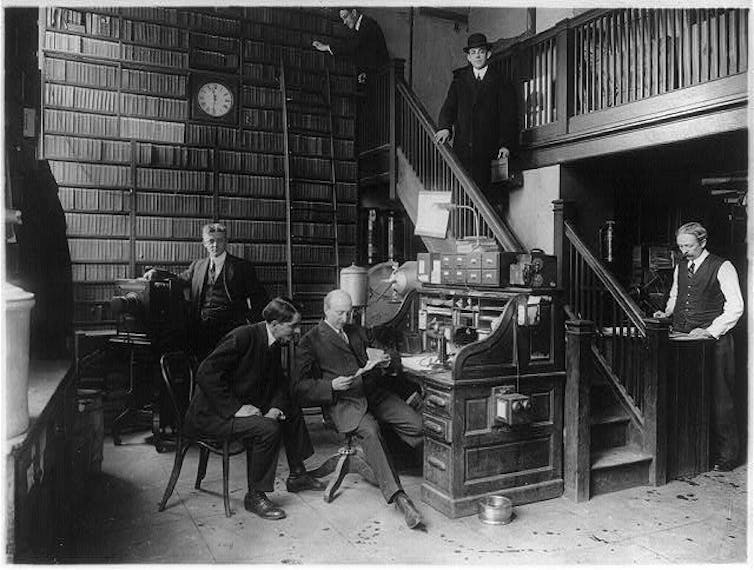

Toward the end of the 1800s and the start of the 20th century, newspapers began to consolidate and grow into big businesses. A good example was the Whig in Kingston, Ont.

In the 1830s, a local Kingston doctor, Edward John Barker, owned and managed the Kingston British Whig. Today, its successor, the Kingston Whig-Standard, is the property of Postmedia — a large Toronto-based company staffed by trained reporters and supported by global investors.

From four-page spreadsheets to Facebook

There are links between cash-strapped editors of the 1830s and the torrent of online articles on sites like Facebook.

Facebook and other social media platforms with “newsfeeds” take on the modern-day role of that long-gone four-page editor, cutting and sorting news stories.

In the 1830s, editors did not copy everything they found in print. There were clear, if unwritten, rules on the “cutting and stealing” of news from one another.

By the standards of the 1830s, Facebook is a bad editor. The site and its algorithms do not copy and share the “right” stories. What happened to those unwritten rules? Should we put money into regulating journalists and determining what stories people see?

Government support as part of the solution

It turns out that newspapers in the 1830s had extensive government support.

A local editor could not get a paper circulated or gather news from other locations without the postal system. The U.S. postal system was “a nationally subsidized information infrastructure.”

Newspaper owners in that era had another big advantage over their counterparts of today: They could ship their papers across the U.S. at deeply discounted rates. It cost one cent to send a newspaper 100 miles; it cost 24 cents to send a letter or package — with the same weight as the newspaper — only 30 miles.

Upper Canada also had a large postal service. By 1841, there was a post office for every 1,800 inhabitants. The colony’s postal service also had a preferential rate for newspapers that was about eight to nine times lower than for a letter. On top of that, “editors could also send a copy free of charge to their colleagues.”

These highly subsidized arrangements also applied to international newspapers. Starting in 1834, a British newspaper arriving by ship in Halifax would be shipped to its destination anywhere in Canada free of charge.

Think about what this level of support would mean today: Unlimited free bandwidth? Free domain names? Free servers and routers? A newspaper shipping and delivering its paper across Canada for pennies on the dollar?

True believers

Another lesson we can gain from the editors of the 1830s involves values. Many of the papers I studied were money-losing ventures and yet editors would continually start and restart papers in the face of riots, financial failure and imprisonment.

Newspaper owners spoke of the great importance of newspapers to the public and truly believed in the capacity of news and knowledge to improve society. Newspapers of the time were filled with such quotes as “the printing fraternity, ever the ardent friends of Liberty.”

Consider Dr. Barker and his Whig. In 1837, in retaliation for Dr. Barker’s reform positions, opponents poisoned his dog. Yet, Barker remained at the Whig until 1871.

Most modern media owners may be less willing to put values before profits.

However, some extreme-right media outlets have managed to receive private funding to produce biased news that is, doctored or involves outright lies and quack conspiracy theories.

Because of their deep pockets, they operate without needing to look at profits. Breitbart media is one example: The billionaire Mercer family provided $10 million to operate the website and provided material support to its contributors.

We have seen these problems before. The journalists of almost 200 years ago dealt with a media landscape with surprising similarities to today’s internet age.

They met it, however, with two things today’s media need more of: Government support and a commitment to get out the news, and a commitment held not just by the beat reporter but by head office as well — no matter what the barriers.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.