Last year, COVID-19 escalated to one of Canada’s leading causes of death. Gradually, and then with a gripping feeling of permanence, everyday life slowed to a halt, enveloped in uncertainty, as the death toll climbed steadily upward. Today, more than 22,000 people in Canada have died of COVID-19.

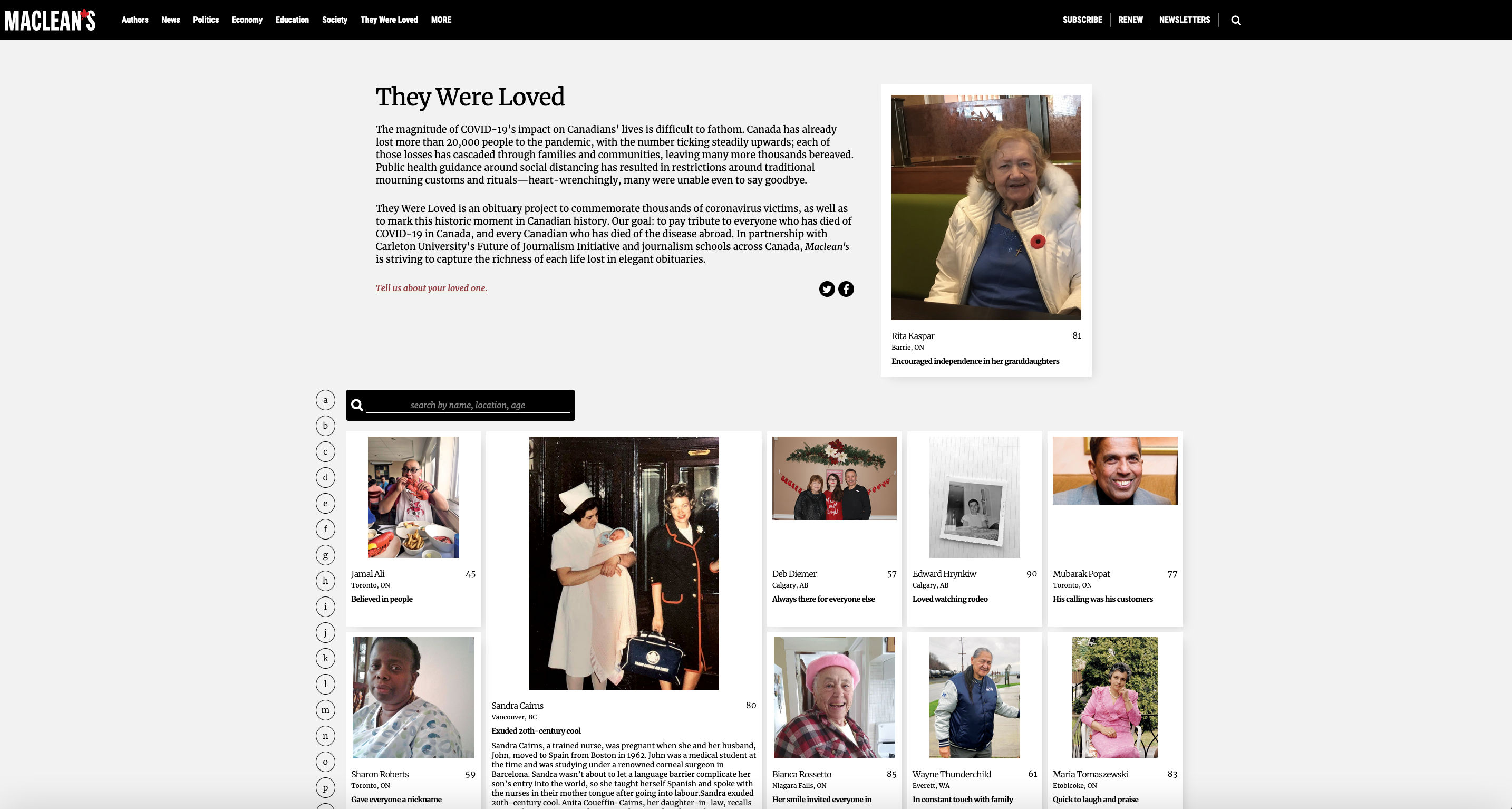

As enormous as that number is, statistics can be desensitizing. They’re shocking until they aren’t anymore. Alison Uncles, editor-in-chief of Maclean’s, wanted to put faces to the numbers, to humanize the pandemic and honour its victims. She set out to publish an obituary for every life lost to COVID-19 in Canada, as well as every Canadian life lost abroad.

“It was an impossible undertaking,” said Brett Popplewell, assistant professor of journalism at Carleton University. “She quickly realized that their newsroom couldn’t handle that. She was looking to figure out how to essentially mobilize an army of journalists.” He stepped forward with Carleton’s Future of Journalism Initiative, a collaborative research hub bringing journalists, academics and students together for projects in the field.

Popplewell co-ordinated with J-Schools Canada/Écoles-J Canada to recruit journalism students from across the country to write the obituaries. Meanwhile, support from the Giustra Foundation (and more recently, Mindset Social Innovation Foundation), made it possible to engage a journalist-in-residence.

Katherine Laidlaw has been tasked with building a database of the COVID-19 casualties: the names behind the numbers, as well as the loved ones left in the wake. She then sees the obituaries (800, to date) through from the classroom to publication.

“One thing I try to impress on [the students] … these are not stories about how someone died, there are a lot of stories about that already. These are stories about what a person poured their time into, their passions, where the love in their life came from, who they cared about, the things that they pursued,” she said.

Popplewell brought the project into his classroom of 17 students, producing 34 obituaries. “For the students, it’s been a positive experience because it’s pretty powerful journalism. It’s putting faces to a pandemic that, in the minds of some, is an invisible pandemic,” he said. “These are just statistics until they are brought to life. And that’s what the obituaries do.”

In August of 2020, the first of what will eventually be thousands of obituaries were published through Maclean’s They Were Loved series. Each month, a selection of obituaries will be run in print, and all will be catalogued online.

“We’re starting to get some feedback now from readers who are being touched by what they’re reading. You’re starting to see families reaching out to mention to us that they have lost somebody too and they would like to be part of this,” said Popplewell. “There is something for the historical record here. And the fact that it is digital is an added strength because it’s more accessible.”

The Maclean’s initiative is one of a few large format obituary projects that have been created to memorialize loved ones in a time of immense and sprawling grief.

In May of 2020, about two months after COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, the Montreal Gazette’s obituary section spanned eight pages, up from its usual three. This was following a 45 per cent spike in obits published between March and April 2020, as well as a 38 per cent spike from the year prior.

When faced with mass mortality events like the opioid crisis and the coronavirus pandemic, obituaries are a way to make sense of human impermanence. They have the ability to give closure, even if the manner of death has not.

The Globe and Mail, the Ottawa Citizen and the Toronto Star have all reported increases in the number of death notices requested since the outbreak began.

In the United States, where COVID-19 has claimed the lives of more than 500,000, projects such as Those We’ve Lost (the New York Times) and The Loss (NBC News) exist to honour the country’s growing number of coronavirus fatalities.

Meanwhile, Poynter has compiled a running list of journalists and media professionals, hailing from all over the world, who’ve lost their lives to the virus, alongside excerpts from their obituaries and links to each piece.

There is also an emerging trend of lengthier, more detailed obits and death notices, akin to eulogies, as family members mourn from afar and find solace in storytelling. The Globe and Mail, for instance, reports that the average length of their death notices increased by 50 per cent between April 2019 and April 2020.

When faced with mass mortality events like the opioid crisis and the coronavirus pandemic, obituaries are a way to make sense of human impermanence. They have the ability to give closure, even if the manner of death has not.

In spite of the important part obits play in the grieving process, the trade of obituary writing has been in flux for some time. Obituaries are one of the world’s most enduring literary conventions, predating the invention of the printing press, but veterans of the craft are nearing the ends of their careers, with no proteges to speak of.

Sandra Martin, journalist and author of Working the Dead Beat, wrote the bulk of the Globe and Mail’s obituaries for 10 years. When she phased out of her full-time role in 2014, the paper opted against hiring a dedicated obit writer to replace her. Today, it is commonplace for obituary columns to be assigned to freelancers or to staffers as supplementary work. You’re also more likely to read an obituary written by friends and family — or the deceased themselves.

Ordinary people writing obituaries is what led David McConkey to found his website obituaryguide.com in 2007. McConkey, a freelance columnist with the Brandon Sun, was prompted to create his virtual guide after perceiving an increased awareness of death-related issues and conversations surrounding mortality.

“More people are thinking about being prepared for their own deaths,” said McConkey. “I think today there’s a darkness in the world that we’re all more aware of and I think that’s reflecting in obituaries. Obituaries reflect the age we’re in, that’s inevitable.”

Obituary conventions have evolved significantly throughout the ages. Death announcements date back to as early as 59 BC in the Roman Empire, when official notices would be distributed on carved stone.

But the lengthier, narrative-style obituaries we see today can be traced back to the Daily Telegraph, under the editorship of English journalist Hugh Massingberd, in the late 1980s. Massingberd subscribed to the school of thought that an obituary should relay details about a person’s life, not just their death. He championed the importance of truth in obituaries, no matter how peculiar or painful.

More than 30 years later, technology has given rise to new and innovative ways of reporting on death, to a much larger audience than ever before. Today, social media and digital memorial pages, where users have greater control over things like narrative, editing, sharing, and privacy, make it possible to create a virtual bookmark in honour of the deceased.

And with more readers to relate to the idiosyncrasies of human behaviour, there’s more occasion than ever for frankness when it comes to dishing about the dead.

And though the nature of Canada’s death beat is shifting, people mourning in relative isolation have brought the responsibility of the obituary into sharper relief.

Perhaps most significantly, the digital age has given way to a new manner of catharsis and a commemorative way of mourning. For friends and family of the deceased, digital avenues provide a unique and interactive way to grieve, share stories and chime into the conversation where there wasn’t the option for a conversation before.

The modern obituary is, understandably, vastly different from its historical form. Obits plucked from various points in history might possess a distinctly religious tone or a glorified reverence or even a theatrical quality, but today’s obituaries celebrate the shape of a life; what the deceased loved, who they loved and how they lived.

“Obituaries are an opportunity to be almost mindful of someone’s life. They can be part of a meditative experience,” saids McConkey. “I see the craft as only improving in the future, because I think it still fulfills a real need that we have as human beings to mark our lives and mark the lives of other people around us. And for society to mark the lives of people in our world.”

And though the nature of Canada’s death beat is shifting, people mourning in relative isolation have brought the responsibility of the obituary into sharper relief.

“One thing that’s happening right now is that the usual rites of grief that we have set up to process death … are not available because we’re in such an isolated time,” said Laidlaw. Many families have not been afforded a proper funeral, or even the chance to say goodbye. She added that, for some, obituaries have stood in for those traditional manners of bereavement, even if in a small way.

“I believe there’s a nobility to this kind of journalism. It’s powerful, it’s personal, it’s empathetic and it’s important,” said Popplewell. “Somebody told me once … that you never really lose someone when they die. And I do believe in that. And these stories really are examples of that, because even though the person is gone, the life has been lost, the stories don’t need to be lost. They live on in the people who retell them.”