The summer of 2021 has been an abysmal demonstration of Canadian media’s ability to properly address the issue of climate change. From the federal election, to a ground-breaking report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, to extreme weather events brought on by climate change, again and again the industry has failed to adequately inform the public on arguably the biggest challenge humanity has ever faced.

On Aug. 9, the UN IPCC released its most dire report to date, outlining current science and explaining the increasing gravity of the threat. The report detailed how international goals of limiting warming to 1.5 or 2 C are quickly slipping away from the realm of possibility. The 1.5 C threshold could be crossed as soon as the early 2030s.

Only days later, Canada entered in a federal election campaign. And yet, there has been very little dissection of party platforms on climate change policy.

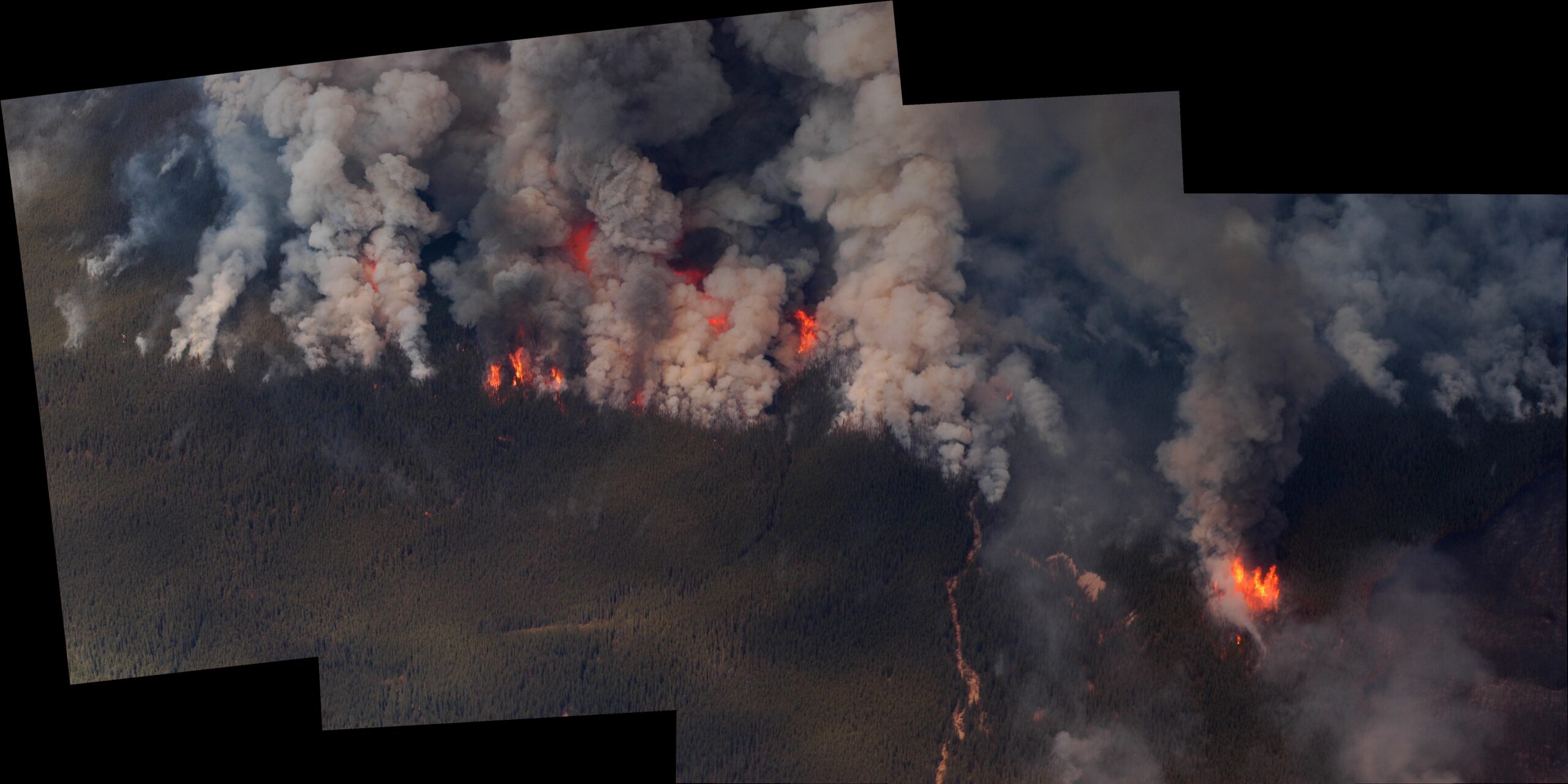

This all comes after weeks of Canadians bearing witness to the apocalyptic sights of unprecedented extreme weather events that will only increase in frequency and intensity as climate change becomes more severe in years to come.

But even after years of critiques and a mountain of analysis and resources surrounding best practices, Canadian digital media continues to fail to provide the public with the context needed to properly understand the situation at hand.

Of 100 articles randomly surveyed from local to international outlets reporting from British Columbia to Manitoba this summer between June 24 and Aug. 3, only 30 articles made any reference at all to climate change or global warming.

(That count excludes any instances where the only reference was in using the title of the federal government department Environment and Climate Change Canada.)

Even in articles where words like “unprecedented” are featured in headlines or the subject matter is record-breaking drought or heat conditions, references to climate change very rarely appear. Particularly curious are the articles where interviewees are clearly trying to put climate change forward as an explanation, and yet the article sidesteps the issue.

For example, a July 19 article by CBC News has a professor from the University of Calgary citing climate models, but the article neglects to explain that climate models are used to extrapolate how climate change is anticipated to play out as the world continues to warm.

In other instances, the issue is just a clear lack of context, such as in another CBC article that reads: it “must be hot when the picnic tables are melting.” The article explains that the strain on municipal infrastructure experienced during a summer heat wave isn’t common in Edmonton’s cool climate. But the article neglects to mention that the Prairie climate has already warmed by more than 1.7 C on average since 1948 and will continue to warm further with time.

Another article mentions the accelerated melting of glaciers changing a region’s water system, but again, no mention of climate change.

Two of the three outlets that wrote about Winnipeg having the driest July in 150 years neglected to mention climate change.

It’s as if journalists have forgotten to answer the question of “why” in their reporting.

“People seek information. They want information because they desire certainty and control about the world around them. And if we’re not providing the public with information about what they can do about climate change as part of coverage of climate disasters, we are leaving them in a situation of profound uncontrollability and lack of certainty,” said Sean Holman, a journalism professor at Mount Royal University.

“So we are not performing our service role, as journalists, when we do not include this information as part of our spot reporting on climate disasters.”

The Canadian Press advised in its most recent style guide edition to include information about the general relationship to climate change when reporting on extreme weather events, by including lines such as, “Scientists say climate change is responsible for more frequent and more intense storms, droughts, floods and fires.”

Some reporters and outlets have made a clear and concerted effort to make the connections for readers, backed either by interviews with experts, online resources, or both.

Camille Bains at the Canadian Press wrote this about the agricultural impact of drought in Saskatchewan. “Those parched fields are a ‘massive manifestation of climate change that was not predicted to occur this early in the century,’ University of Saskatchewan Professor John Pomeroy said in an interview.”

That’s the context readers need to properly understand the story. It is not a matter of debate; droughts, wildfires and heat waves all have direct links to climate change and these connections have been well documented by researchers around the world — from the IPCC to Canadian researchers hired by Natural Resources Canada to break down and document the impacts in this country by region.

But when journalists fail to make even the most basic connection between these extreme weather events and climate change, it means they also fail to take the next step in helping to document how climate change is already (and will continue) to impact human health, food security and livelihoods.

It means journalists will fail to equip communities with the information and analysis they need to knowledgeably encourage good policy that will mitigate the impacts of climate change in the future — or how to properly evaluate election platforms.

Take, for example, the week-long heat wave that hit British Columbia in June. Reports show that at least 570 deaths in the province occured “as a direct result of the extreme temperatures.”

In B.C., it’s possible to estimate the number of deaths connected to the heat wave, as it was in Quebec when nearly 100 people died in connection to the heat wave in 2018. However, most other Canadian provinces make no effort to count the number of people that fall ill or die in extreme heat.

Heat-related deaths are one of the most direct human health impacts of climate change. The World Health Organization said that because climate change has increased the frequency, duration and magnitude of heat waves, the number of people who will be exposed to heat waves increased by 125 million between 2000 and 2017. The WHO roughly estimates that 166,000 people died between 1998 and 2017, with 70,000 dying in a single summer in Europe.

And yet, journalists in Canada aren’t holding government and public agencies to account for neglecting to track the number of people dying here.

“I think that the reality is that, for so long, the messaging around climate change was that it was a disaster for whales, or disaster for polar bears and disaster for tree frogs. But we really kind of glossed over the fact that in a lot of ways, it’s a disaster for humans, because we – like those creatures – live on this planet,” said Joe Vipond, outgoing president of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment.

“And granted, we have been, to this point, been more adaptable, but not everybody is equally adaptable. And the reality is that as the climate continues to alter, it’s going to continue to have an impact on our health and heat-related deaths just being one of those things.”

Vipond said much the way COVID-19 was found to have disproportionate health impacts on racialized, aging populations, so too will climate change.

In a similar vein, if journalists fail to properly understand and report on the basics of climate change, so too will they miss out on the more complex stories, such as how climate change is already impacting Indigenous communities and northern residents.

Susan Nerberg was a finalist for the Canadian Association of Journalists’ award for climate reporting this year, for her work documenting permafrost thaw in the Northwest Territories, where residents are already being forced to relocate their homes due to the ground disappearing beneath them.

“I think these stories should be on Page 1. Every day. And they’re not. They’re buried somewhere if they’re even in there at all,” Nerberg said.

“We need more of that coverage, not only to see what’s happening there, but also, as these changes become more and more noticeable at lower latitudes, we can learn from how scientists and local communities are learning to predict change, and also to adapt to that change. I mean, it sounds kind of crass, in a way, that we’re going to learn from the people whose lives we’ve shattered. But things will catch up with us.”

Nerberg said she’d love to see climate content become ubiquitous in the Canadian media; she imagines daily carbon emissions reported in the same way stock market numbers are listed every morning on the radio.

Ian Mauro, the director of the Prairie Climate Centre at the University of Winnipeg, said that over the years he believes coverage linking extreme weather events to climate change has improved over time. But he said even more stark is how absent the issue is between extreme weather events.

“We don’t have a consistency of climate reporting that keeps it at the level that it needs to be at, given the real crisis that it represents. It can’t be in fits and spurts. It needs to be done in a sustained way, a systematic way, and in a manner that really does create cultural and societal awareness around the need for bold action,” Mauro said.

“And that’s not advocacy. That is simple common sense; to create an informed and literate public around critical issues in society. I would say that’s good journalistic practice.”

For journalists looking for resources to help cover climate change and extreme weather events, the Prairie Climate Centre is a good place to start as the post-secondary department has published a Climate Atlas that breaks down climate trends by region using different emissions scenarios.

This summer, Natural Resources Canada published the National Issues Report that breaks down climate change impacts in Canada by topic and is based on research compiled from across the country over the course of many years.

Climate Central is an independent organization of science journalists that offers detailed data from the United States, but that often offers good local story ideas that would help organizations to incorporate climate change into daily reporting.

Covering Climate Now, a consortium of international media organizations, has a list of resources to help journalists cover climate change.