By Charmaine Millaire for The Signal

On the crisp winter morning of February 17, 2009, Peter Mansbridge walked off the elevator towards the main doors of the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C. Before reaching the doors he noticed his reflection in a full body mirror, and realized he had paired the wrong coloured pants with his suit jacket. Stunned, he raced towards the elevator to go back up to change. As the doors sealed he thought, “Wow, I really dodged a bullet there.”

After changing Mansbridge began the three-block walk to the White House. Upon arrival he was escorted to the Map Room, a room commonly used for television interviews. Quickly, the room filled with the president’s communications staff, and the press. At 9:13 a.m., U.S. President Obama walked through the crowded room towards Mansbridge with his arm out-stretched for a handshake. “Hi Peter, welcome to the White House.”

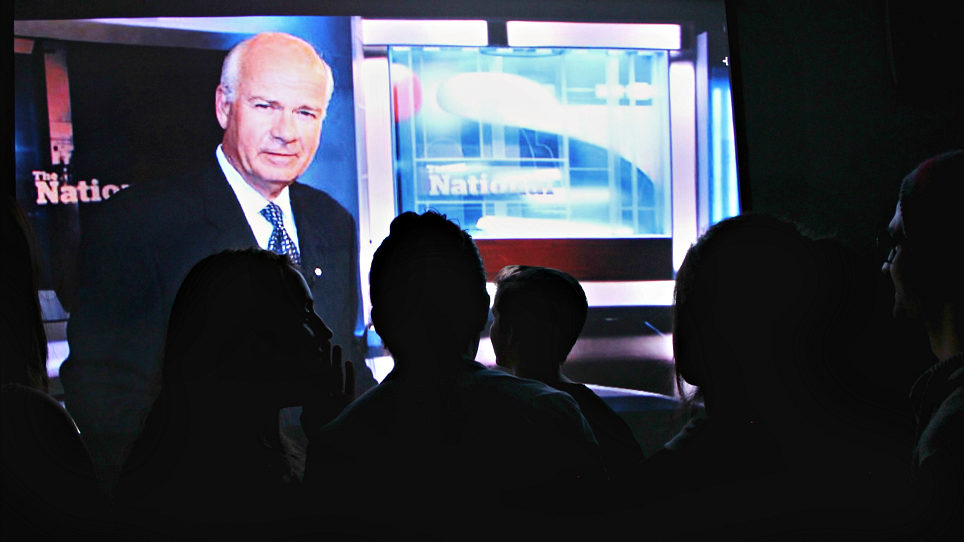

The only Canadian journalist who has interviewed President Obama one-on-one is Mansbridge. He has interviewed numerous leaders, including former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, and His Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan, the spiritual leader of the world’s Ismaili community. CBC estimates 68-year-old Mansbridge conducted over 15,000 interviews in his 48-year career.

There are also controversies. Critics say some of Mansbridge’s decisions have allowed Canadians to question him. This includes giving powerful people, like then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper, a weak interview, and accepting $28,000 to speak at an event for an oil sands group. These decisions may affect the reputation of all journalists, and diminish Canadians’ trust in journalism. It may also affect how some journalists conduct themselves.

So what exactly is Peter Mansbridge’s legacy? How will he be regarded? And how does he regard himself?

An unusual start in journalism

In 1968 the unforeseen happened to a 19-year-old baggage handler in the Churchill, Manitoba airport. The young man was asked to fill in on the intercom to make a flight announcement for Transair. To his surprise, he was approached by the station manager from the local CBC radio station, Gaston Charpentier, and offered a job as host of CHFC’s late night program.

You guessed it – that baritone voice echoing over the intercom belonged to Peter Mansbridge.

After that life-changing moment, Mansbridge spent 20 years as a journalist in Winnipeg, Saskatchewan, and Ottawa. In 1988 he succeeded Knowlton Nash as news anchor for The National and became the Chief Correspondent of CBC.

Friend or Foe?

Friends of Canadian Broadcasting, formed in 1985, is a non-profit, independent watchdog for Canadian programming. Friends’ mission is to defend and enhance CBC programming’s quality and quantity. The main spokesperson, Ian Morrison, has met Mansbridge on more than one occasion, but says he does not “recall” any of these moments. Unexpectedly, Morrison has never been a fan of Mansbridge. Morrison believes Mansbridge has been submissive in interviews, giving powerful people easy questions. The interview with Harper comes to mind. Mansbridge, he says, is “just not throwing his best pitches.”

Morrison thinks Mansbridge is a credible journalist who has covered “great stories.” His coverage from the underground Goodman Subway tunnel at Vimy Ridge in 2014, and his D-Day anniversary coverage are two of Morrison’s favourite Mansbridge moments. But the best way to measure Mansbridge’s legacy, according to Morrison, is to look at the “erosion of viewers” tuning into the National. “His departure at this time is appropriate,” says Morrison. “Like food off the grocery shelves – we are getting close to the ‘best before’ date.”

Through the eyes of a critic

In a third floor office in the Globe and Mail building, hidden behind the screen of a large Mac desktop, sits television critic John Doyle. He spends the work day surrounded by the dull green and beige walls of his office, and watches TV. The TV critic for the Globe and Mail for almost 17 years, he writes columns on shows that range from TV dramas like The Walking Dead to news programs like the National.

Doyle believes a typical, respectable news anchor needs to have a down-to-earth personality to give viewers the sense that he/she is not just an authority figure, but also a human being with whom they can identify. He believes Peter Mansbridge (who Doyle calls Pastor Mansbridge) is the opposite. “He has that pompous quality a pastor might have,” says Doyle. “Built into that demeanor are elements of smugness and remoteness.”

Doyle applauds Mansbridge for one thing: being good at anchoring live events. Doyle believes it’s not a skill everybody in the business has, and it’s notable. But, like Morrison, Doyle believes Mansbridge has failed to ask powerful people tough interview questions. He flashes back to Mansbridge’s interview with former Toronto mayor Rob Ford.

“You just sense there is a tone of deference and obsequious,” said Doyle. “I can’t cite a time where I thought he was exceptional in an interview – and I think that says something.”

Canada’s most trusted man

Stephen Ward, a lecturer in ethics at the University of British Columbia, believes Mansbridge has set the journalism standard for Canadians. In Ward’s eyes, Mansbridge is the Walter Cronkite of Canada. He believes Mansbridge’s strength has always been the ability to convey a sense of fairness and trust to the public. “I admire his even-handed approach,” says Ward. “Even when all hell is breaking loose out there – he always manages to pull you back in.”

The general manager and editor-in-chief of CBC News, Jennifer McGuire, shares a similar opinion. She says Mansbridge has always had a passion to chase good stories, and is “in his element” while doing live-coverage. “There is nobody in the country who comes close to bringing the depth and context of live events like Peter,” she said.

In fact, she believes his best work is in elections, and in times of fast-paced crisis, like 9/11 and the shooting on Parliament Hill in 2014. “He remained so grounded – in a way that built trust with the audience.”

Critics say Mansbridge has had some controversial journalism moments, including referring to one of the world’s most famous models, Gisele Bündchen, as “Mrs. Tom Brady” during his 2016 Rio Olympic coverage. But they say his most controversial moment was when he accepted a $28,000 speaking fee to speak at an event by the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers.

When an audience detects a bias or a conflict of interest in a journalist’s reporting, it drags down the audience’s confidence in the news, and in journalism. Since Mansbridge’s speaking fee incident, followed by CBC’s Amanda Lang accepting speaking fees and appearing to have a conflict of interest with the Royal Bank of Canada, CBC’s policy on accepting speaking fees has been updated.

Doyle feels taking money from an organization compromises a journalist. “I think it’s very foolish for someone in Mansbridge’s position to do speaking engagements with major corporations.”

The end of an era

Mansbridge believes being criticized creates a healthy atmosphere. He says he receives legitimate criticism from viewers, and sometimes goes the extra mile to phone them to discuss their criticisms, no matter where they are in the country. Regardless of the critiques, he says he has no problems at all, including ethically, with anything he’s ever done.

“If I were to regret anything at all,” said Mansbridge. “It’s that I wish I was a better storyteller than I am.”

After Mansbridge announced, early this September, he was going to step down from the National on Canada’s 150th birthday, July 1, 2017, Doyle wrote a column titled It’s about time: We’ve put up with Mansbridge and his pompous ilk for too long. Doyle said about 50% of readers agreed with him, and the other half did not.

Mansbridge’s legacy may be similar. Many Canadians will be nostalgic, and will continue to respect him. Others will see it as the end of the “father figure delivering the news” era.

Mansbridge hopes Canadians will regard him as being honest, fair, and accurate. “Those three things have always been my guiding lights,” he said.

“At the end of the day, I’m just a journalist – that’s all I am.”

This story was originally published on the University of King’s College The Signal, and is republished here with the author’s permission.