The New York Times and Washington Post are two of the world’s most influential newspapers. Every day, they battle over sources and jostle for a better story. So it’s extraordinary that the two rivals have teamed up to create software to run comment sections.

The alliance began in 2013, at a news industry conference where Aron Pilhofer, the Times’ interactive news editor, and Cory Haik, the Post’s executive director of emerging news products, bumped into each other. The two shared troubles their papers were experiencing with comment sections and decided to work together to fix them.

That conversation would grow into the Coral Project, a collaboration between the two journalism giants, and later Mozilla with its open-source software know-how. The New York-based project aims to use this software to improve comment sections.

In 2015, Andrew Losowsky, a journalist, became the project’s lead. He says, “It came down to everyone seeing the problem, and the problem being too big for any one organization to solve.”

But why keep them at all? Comment sections can give a voice to the voiceless and hold institutions and individuals accountable. They can help journalists write better stories. But now – because of abuse by commenters, the dominance of social media, and the cost of hiring moderators – many high-profile news outlets such as the Toronto Star and Vice are shuttering their comment sections.The future of comments is uncertain. But clues as to what the future might look like can be found both in the ways news organizations use comments today, and in how comments have been used in journalism’s history.

Useful, useless or just plain ugly?

Before comment sections, there were letters to the editor. Both give readers a chance to share their knowledge and opinions, a journalism norm hundreds of years in the making.

Karin Wahl-Jorgensen, a journalism professor at Cardiff University, wrote Journalists and the Publicin 2007, a book about the history of letters to the editor. In it, she identifies two functions of letters to the editor: “Debates over specific issues in the paper on journalism ethics and … engagement in broader public debates.” Modern comment sections also perform these functions.

Letters from the public have been published in papers since the 1600s. They have had a section of the paper devoted just to them since 1851, when the New York Times pioneered the practice.

After hundreds of years, letters and comments from readers are probably here to stay. The question now is whether online comment sections will be the main way readers share their ideas.

Jake Batsell, a journalism professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, says that comment sections are a great way to facilitate the changing relationship between journalists and readers. He explored the issue in his 2015 book Engaged Journalism: Connecting with Digitally Empowered News Audiences.

In this evolving relationship, readers can question a news outlet’s ethical decisions. They can debate each other. And readers with specialized knowledge can add value to an article.

“Journalists need insights from their audience,” Batsell says. “They don’t know everything.”

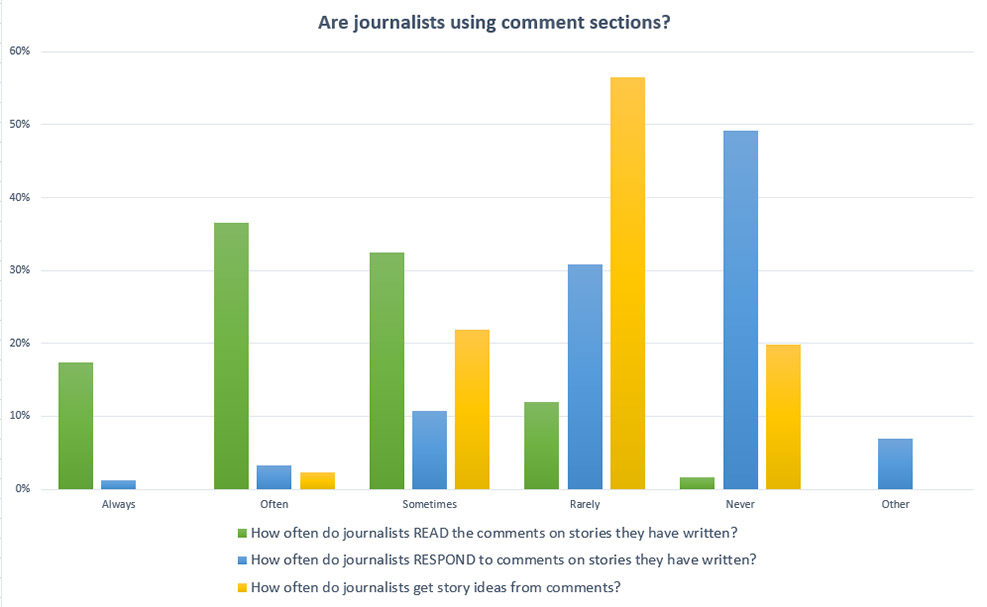

Audience members can also point journalists toward story ideas. A 2011 study in the Newspaper Research Journal, an American publication run by journalism professors across the country, found that 22 per cent of U.S. journalists sometimes got a story idea from comment sections.

And from a business angle, loyal commenters are more likely to buy a subscription.

As compelling as these reasons are, there are serious problems with comments. For one, comments can get ugly.

A 2015 study in the Howard Journal of Communications, published by Howard University in Washington D.C., found that commenters are quick to polarize even neutral topics. One-quarter of all articles that do not deal with race have at least one race-based comment.

Another problem is that many comment sections are underused. For example, Bloomberg Businessditched its comment section partially because “less than one percent of the overall audience” was commenting.

Even if the comment section isn’t often used, it’s still expensive to run. News outlets are businesses, no matter how civic-minded they are. For comment sections to survive, they must help pay the bills – or at least not add to them.

When news organizations look at the pros and cons of comment sections, they generally come to two conclusions. Some decide to ditch their sections and engage readers differently. Others elect to keep them, and invest time and money to improve them.

Trevor Adams, the senior editor at Halifax Magazine, chose option one. Earlier this year, his lifestyle magazine cut its comment section.

No one seemed to care.

“Not one person said, ‘Hey, where did your comment section go?’,” says Adams.

This didn’t surprise him at all — his magazine’s comment section was rarely used. And when it was, it often “vandalized the story” with statements that were sometimes inaccurate and other times hateful.

Adams also found that people were commenting on the magazine’s Facebook and Twitter far more than in the comment section.

Many news organizations have made this migration to social media. When they close the dedicated comment section, they’re simply being pragmatic, Batsell says. “They’re deciding to go where the fish are, and the fish are on social media increasingly.” Organizations like NPR closed their section for this reason.

And Adams says nothing is lost when this happens. “I don’t see any news outlets’ comment section doing something that their social media isn’t already doing better.”

Other news organizations see things differently.

The CBC values its comment section because it has the ability to create a national conversation.

Jack Nagler works at CBC as the director of journalistic accountability and engagement. His job is to manage the corporation’s relationship with readers across the country.

“What better opportunity is there for folks to come together and find out what each other thinks than to be able to comment on stories and engage in debate?,” he says.

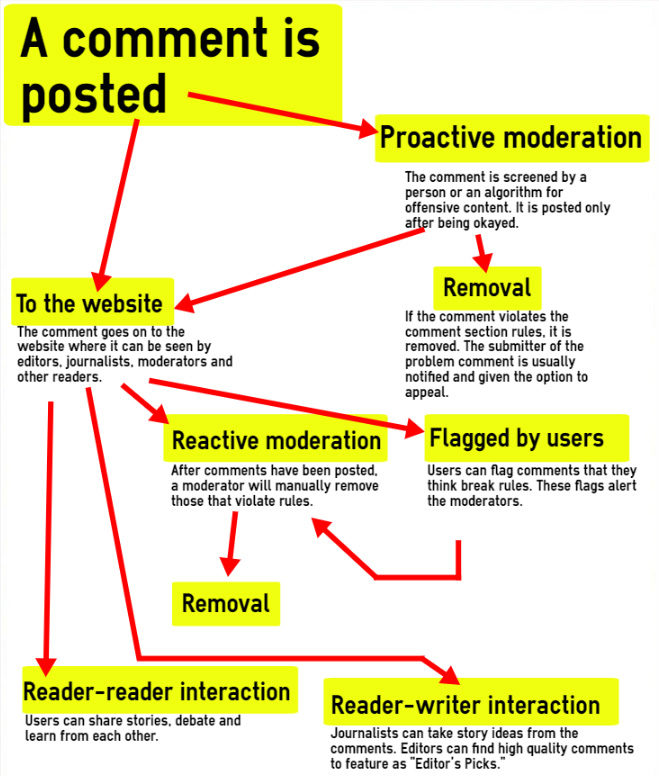

Seeing value in comments doesn’t mean being blind to their flaws. The CBC is constantly experimenting to make its comment section more productive. At times it’s used reactive moderation, when comments are moderated after being publicly posted. Currently it uses proactive moderation, when comments are screened beforehand. It’s tried adding accountability by forcing commenters to attach their names. And it’s tried closing comments on sensitive topics like indigenous or transgender issues.

These strategies have been tried by news outlets across North America. They often make comments more civil, but there is still room for improvement. And improvement requires time and money.

The Coral Project is the result of a great deal of this money – $3.89 million U.S. The financial basis for the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Mozilla to build on was granted by the Knight Foundation, which funds U.S. journalism and arts initiatives.

The Coral team conducted interviews in 150 newsrooms in 30 countries to identify common problems with comment sections.

“The real problem with comment sections is that we don’t know what we want from them,” says Andrew Losowsky, the project’s lead. “We go in with no strategy, and what we get back is what happens when you just say, ‘Do whatever you like’.”

Civil and on target

The project aims to clarify what sort of comments a news organization wants. Instead of leaving readers to comment in a blank box, Coral software can prompt readers by offering a specific topic or question. Trials by the Washington Post have found that this keeps comments more civil and on topic.

The project also wants to make it easier to highlight quality comments. Losowsky says that while news organizations are quite good at removing comments which break site rules, they’re not so good at showcasing quality comments.

Coral plans to change this with software that allows news organizations to see a commenter’s history. They are able to see how often a user comments, how many likes or replies they get, and the average length of their comment. By searching using parameters like these, editors can much more easily find quality comments to feature. Losowsky says this kind of encouragement is key to building a community of readers.

The Post started using Coral software earlier this year. Since then, 15 other newsrooms in the Americas, Europe and Australia who have also installed the software, which is free to use. The project’s software is free because people at the project, like Losowsky, think that the more newsrooms with functioning comment sections, the better. They could play a crucial role in improving journalism’s relationship with the public.

A 2016 Gallup poll put U.S. public trust in journalism at its lowest point in polling history. Only 32 per cent of people had a great or fair amount of trust in the news. One of the hopes of the Coral Project, Losowsky says, is that readers will feel a part of the news-making process, and so will have more trust in it.

“Trust isn’t a thing that you sell once and then you’re done. It’s a relationship that requires ongoing interaction.”

This story originally appeared in the University of King’s College Signal, and is republished here with the author’s permission.