This series was funded by readers like you through donations to the J-Source Patreon and FutureFunder at Carleton University.

In the summer of 2018, Angela Long embarked on a 22,000-kilometre journey, traversing eight provinces and a territory – from Dawson City, Yukon, to Cape Breton, N.S. – to learn from residents, reporters and experts about journalism’s importance in rural markets. In this series, she tells the stories of local news survivors and the roles they play in bolstering their communities.

The Eastern Door is hard to find. “Just follow this line,” says a staff member at the Kahnawake Welcome Center. He draws what appears to be a simple route to the weekly community newspaper owned by journalist Steve Bonspiel with blue pen on a complimentary map.

When you cross the Honoré-Mercier Bridge, you cross more than just the St. Lawrence Seaway. Stop signs change from French to English and Mohawk. The ubiquitous Jean Coutus and Metros of Quebec are replaced by businesses with names like Iron Horse Wear House and Kambry’s Smoothies. The line on the map weaves through the town, past a monument with an 1812 Mohawk warrior holding a tomahawk and a rifle, a full parking lot in front of the Kahnawake Band Council – the spire of the 17th century St. Francis Xavier Mission rising above it all, into the grey sky.

Of a traditional homeland spanning approximately 36,000 sq. km. with the St. Lawrence River Valley forming its northernmost border, the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) of Kahnawake now reside on a 49 sq. km.- reserve. The First Nation forms part of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy – the People of the Longhouse – bound by the Great Law of Peace – a democratic form of governance in existence centuries prior to European contact. Because of their eastern location, the Mohawk are known as the Keepers of the Eastern Door.

It’s been nearly 350 years since Jesuit missionaries wrote about Kahnawake in accounts such as the Annual Narrative of the Mission of the Sault from Its Foundation until the Year 1686, in which Indigenous residents were referred to as “Savages.” In more recent centuries, mainstream media joined the chorus, with publications such as the Toronto Star using terms such as “squaw” and “red-skin” from the early 1900s throughout the ‘30s and ‘40s, according to Les Couchi, a member of the Nipissing First Nation who, in 2017, spent months sifting through the paper’s archive.

While the terms may have changed, “colonial stereotypes have endured in the press, even flourished,” say University of Regina professors Mark Anderson and Carmen Robertson in their 2011 book Seeing Red: A History of Natives in Canadian Newspapers. From an 1873 article in the Montreal Gazette describing Indigenous people as “an incubus not so easily removed” to a 2007 Magaret Wente column in the Globe and Mail saying “some cultures are too toxic to save,” the authors examine Indigenous representation in Canadian media until as recently as a decade ago. Backed by nearly 60 pages of notes and a 15-page bibliography, Anderson and Robertson provide evidence that mainstream media have “aided and abetted” in the marginalization of Canada’s Indigenous population, creating an enduring legacy of racism and “shaping the nation’s colonial story.”

Since 1981, the people of Kahnawake have been shaping their own media. It started with a radio station, then, a newspaper. Now the town, with a population of around 8,000, has two radio stations, a TV station and two weekly newspapers, all independently owned by members of the Mohawk Nation, with the exception of K103.7, a radio station owned by the community.

Kahnawake is not alone. The town’s thriving media scene forms part of a growing network of dozens of Indigenous-run publications, community radio stations and television broadcasters throughout the country. Such a network, according to author Valerie Alia in The New Media Nation: Indigenous Peoples and Global Communication, has been an example to a global Indigenous movement seeking platforms where historically underrepresented voices join “global choruses.”

On the front page of the latest Eastern Door – a newspaper founded by Kenneth Deer in 1992 as a response to the media’s handling of the 1990 Oka, Que. Crisis (also known as part of a long history of resistance) – a little boy wearing beaded moccasins smiles. “Rock your mocs!” reads the headline, a call to swap shoes for moccasins every Wednesday of Cultural Awareness Month in April.

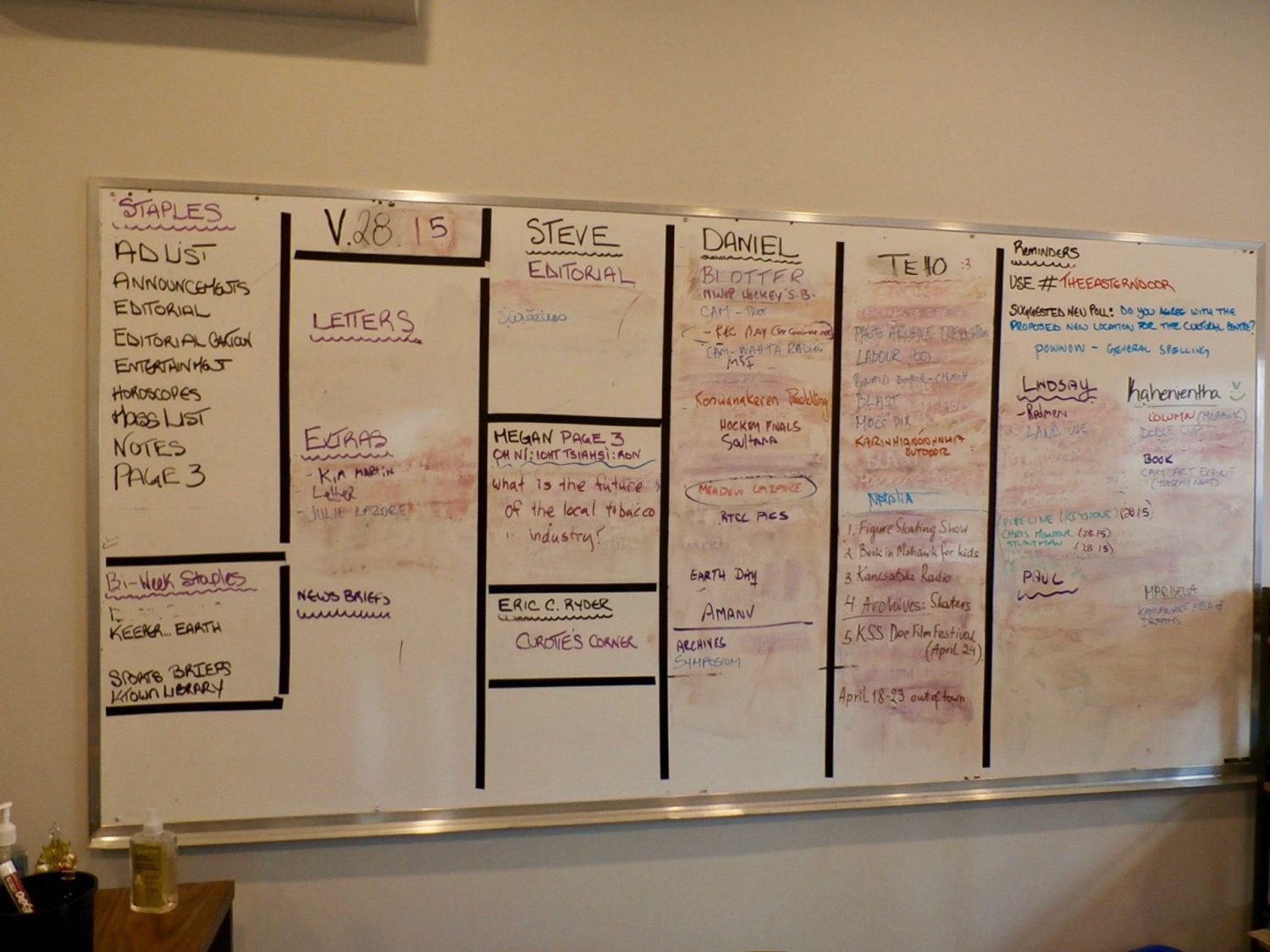

Bonspiel, who bought the 27-year-old, two-dollar-an-issue newspaper ($51 a year for a digital subscription) available at about 60 outlets throughout Kahnawake Mohawk Territory from Deer in 2008, has barely sat down at the conference table in the office’s basement when his phone lights up. For two hours, alerts of messages and calls arrive in a steady stream.

“It never ends,” he says. There’s always “a million things” to attend to. “If I don’t turn it off sometimes,” he says, “I’ll go nuts. I’ll lose my mind.”

Bonspiel is overseeing ad sales, producing a telephone directory, organizing a big fundraiser and the 23rd annual spring cleanup, participating in Cultural Awareness Month, waking up at 4 o’clock in the morning every Friday to deliver newspapers. He’s editing stories, taking note of story tips the community offers up 24 hours a day. “I received five tips just over the weekend,” he says, picking up his phone, now on mute. “They want me to do a business plan,” he says of the caller, sighing.

In addition to running a newspaper and overseeing a full-time editorial team of two, and, usually, four office staff (“I’m down my administrative/production assistant right now,” he says), along with a stable of contributing writers and cartoonists, Bonspiel is the resident troubleshooter for its newly constructed office. If it weren’t for things like the sump pump always going, he might be able to relax a little more on the back porch facing the forest line.

But sump pumps aren’t necessarily Bonspiel’s biggest drain. For years he has been fielding nasty comments about controversial stories published in the Eastern Door. While he rarely responds, he files these away, along with screen shots people send him of comments made elsewhere by those he calls the “Facebook tough guys” who like to threaten him on a regular basis.

“They want me dead,” he says. “They want me out of town.” They’ve threatened to burn down his house — on the same lot as the Eastern Door office — where he lives with his wife Onawa Jacobs, who has since given birth to a baby boy. (Once Bonspiel flew home early from a conference because of such a threat.)

Readers take issue with stories the Eastern Door doesn’t back away from, stories that don’t always cast the community in a positive light and where other media may “tread lightly,” says Bonspiel. These range from their coverage of the ongoing debate about Kahnawake Membership Law and residency – for which Bonspiel won a Michener Citation of Merit in 2010 – to those about drunk driving convictions and drug busts.

Bonspiel sees these kinds of stories as part of a bigger picture. “We stand up for the community,” he says. “We stand up for the little guy.” He sees the Eastern Door as the community’s “conscience,” its pages a place to “effect change.”

A quick glance at any edition of the Eastern Door will show that effecting change also includes positive coverage. Most recently this includes showcasing the latest works of a local artist, a group cycling for charity, the 45-year career of a community health nurse. In addition, the paper has donated hundreds of thousands of dollars over the years, says Bonspiel, either through free advertising or fundraising.

Nevertheless, some community members still get “pissed off,” says Bonspiel.

“They do all kinds of things to knock you down,” he says. “They share horrible memes, they call you all kinds of names. Those types of people don’t see me as a person. They just see me as the Eastern Door.” Bonspiel pauses, taking in the table covered with books and notepads and a sign that reads “support local news.”

“But I’m not Donald Trump,” he says. “I’m not the president of the United States. I’m not a celebrity, I’m not a movie star, I’m not a rock star. I’m just trying to run a little business here.”

For years this little business has been garnering a lot of attention.

In 2018, Bonspiel was named journalist-in-residence at Concordia University in the third year of the program. At the latest Quebec Community Newspaper Association awards, the Eastern Door took home more than a dozen awards, including best editorial page and best news story. In 2017, for the second year in a row, what was then called the Canadian Community Newspaper Association (in 2017 the Canadian Community Newspaper Association and the Canadian Newspaper Association merged to form News Media Canada) awarded the Eastern Door best overall newspaper for its circulation group in the country.

Such awards mean a lot to Bonspiel.

“They just show that we are on par with other newspapers that have totally different realities, totally different histories, totally different stories,” he says. “I’m proud because it shows that we are doing our job, we are doing good journalism.”

As an Indigenous reporter, Bonspiel’s path to such success was different than most mainstream non-Indigenous journalists, he says.

“We grew up in a different reality,” he says. “I grew up on a reserve where, let’s face it, nobody really had money when I was a kid, you know. I grew up in Kanesatake where we don’t have any infrastructure because we barely have any businesses. There’s nothing to look up to. There’s very few role models.”

As a result, says Bonspiel, he wasn’t encouraged to go on to higher education and only has a high school diploma. He spent part of his early 20s working in downtown New York City as an ironworker (an occupation shared by numerous Mohawks since 1916), building skyscrapers. He also worked as an electrician’s assistant in Florida, sleeping on a friend’s floor, earning less than $1,000 a month.

“But I knew somehow — all that stuff had to add up to something later.”

If Bonspiel compares himself to other non-Indigenous journalists who often come from more affluent backgrounds, he sees they’ve always had a “failsafe.” They have family who will bail them out, he says.

“Starting out as an Indigenous journalist I didn’t have any failsafes,” he says. “If I had failed, especially early on, I didn’t know where I’d get my next meal, you know? If you fail? You’re done. That’s it. See you later.”

What some Indigenous journalists sacrifice to get where they are makes them stronger, Bonspiel says. “Not to mention the fight that we have,” he says. “We have to fight all the time to prove our rights, to sometimes prove our lineage. We’re fighting the white guys. We’re fighting the guys on the reserve. You’re fighting everybody. So, because of that,” he says, “you make a good journalist. You know what it is to fight for what you want. You’re telling the stories of those people. You see yourself in them, regardless of their opinion.”

In the end, says Bonspiel, even though he’s sometimes exhausted, even though some years they’re barely in the black (if there are any rich listeners out there, he jokes), what keeps him going is a belief in himself and a belief that this fight is worth it.

“Running a newspaper is hard and telling the truth is hard,” he says, “and nobody in the world ever made a difference without adversity.”

The more the merrier

Back in the heart of Kahnawake, Greg Horn sits in the office of Iorì:wase –“news” in the Mohawk language – coincidentally the original office of its main competitor, the Eastern Door.

Horn has spent most of his 22-year career as a journalist in this office, he says. After having worked at the Eastern Door as a summer student from Concordia in 1997, Horn switched from history to journalism. For 11 years he worked at the Eastern Door until its sale to Bonspiel in 2008. That year, Horn saw the potential for an online news source in Kahnawake and branched out on his own.

In 2012, after his website reached a million hits, Horn started to consider expanding into what many media outlets were downsizing or eliminating altogether – print. For years, says Horn, readers and advertisers were asking for a print product. Horn listened. In 2013, he launched the twice-a-month Iorì:wase. In 2015, he went weekly.

In a town of such a small size, Horn isn’t concerned about competing with the award-winning Bonspiel, he says in a May 2019 phone interview. Horn refers to his Google Analytics stats, which he says records between 5,000 to 10,000 unique visitors a week “from all over the place.” Both papers have thousands of Facebook and Twitter followers and weekly print circulations of a 1,000 or more.

“We’re all here, really, to keep our community informed,” Horn says, “and I think the more media outlets we have, the better.”

Iorì:wase espouses the philosophy that there are a lot of good things in the community, and in sister communities, “that don’t always get told,” he says.

Horn also experiences blowback from the community for some of the more “uncomfortable” and “polarizing” stories that involve incidents such as arrests or murders, or who is legitimately a member of the Mohawk community.

“It’s been a while since I’ve received a really good death threat,” he says, “but, I mean, it’s happened. I don’t know any journalist really that hasn’t had something like that happen.”

While Horn knows it’s their job to report on those kinds of stories, he would rather focus on the more positive elements of the community, he says.

“The old journalism adage that ‘if it bleeds, it leads’ — I think that when news happens you have to report it, but I also think it’s always better for people to know that it’s not just bad things that are happening,” he says. Horn thinks it’s important for communities to acknowledge the “people that are working hard to make sure that all these good things that are happening,” he says. “There’s people behind these things that are making their community go — do you know what I mean?”Horn says he sees part of his role as telling these stories, and helping out local, grassroots organizations such as Skátne Tsi Tewaie’wen:ta – Together We Will Heal, an “inclusive collective based in Kahnawake focused on raising awareness about substance abuse and addictions within all Onkwekonwe communities,” according to its website. Horn partners with them to “help them tell their stories,” he says. He also partners with Iakwahwatsiratátie, otherwise known as the Language Nest — a non-profit immersion program for parents or caregivers of children under four — offering online, biweekly Mohawk lessons by video, accompanied by a print version in the Iorì:wase.

With a focus on embracing technology — offering a free Iorì:wase app, free online access, and including as much video as possible — Horn says they will strive to “stay ahead of the curve.”

In addition to the challenge of staying current, accessible and newsy, Horn says he also thinks about the role he occupies given the history of mainstream media coverage of Indigenous communities.

“They tend to cover Indigenous issues when it’s controversial or something bad has happened so that creates an issue of trust between our communities and the mainstream media,” he says. “If mainstream media is only coming here when something bad is happening, it shows they only care when bad things are happening and not talking about the good things that are happening, all the things that happen in communities every day that are newsworthy.”

One example of mainstream media paying Kahnawake a visit for a good news story occurred just a couple weeks ago, says Mohawk Council political press attaché Joe Delaronde in a May 2019 phone interview. Global News picked up a story that originally appeared in local media about a Kahnawake Sports Complex’s Zamboni driver who was retiring after 33 years.

“People just loved that story,” he said.

While recently mainstream media, for the most part, has worked towards being “more balanced in their coverage,” says Delaronde, who deals with the media on a daily basis, this hasn’t always been the case. The Oka Crisis, he says, whose aftermath affects their community to this day, provides a perfect example.

Numerous researchers have analyzed media coverage of the 78-day standoff at the site of a proposed golf course which saw the deployment of 3,700 troops. A 1996 thesis paper by Elizabeth A. Keller analyzed 1,674 articles written by the Gazette and La Presse where nearly 100 per cent of the summer of 1990’s front pages featured “war zone” images of Oka. While some coverage portrayed the Mohawk’s historical land claims in a positive light, Keller noted, negative terms such as “professional terrorists,” “English warriors,” and “foul-mouthed exhibitionists” frequently described the Mohawks.

“We didn’t always feel like we had a fair shake,” Delaronde says, “so by having our own media, our own people are reporting on issues and it has worked to our advantage.”

The release of the final report from the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigneous Women and Girls provides a more recent example of skewed media coverage. A Canadaland article deems mainstream media’s debate about the report’s use of the word genocide characteristic of a “dismissive, systemically racist, settler-colonial state.” Indigenous-run outlets tended to focus on other matters, such as the report’s 231 Calls for Justice. An article in the Eastern Door included the perspective of local activist Cheryl McDonald, whose sister disappeared and was found dead in 1988. “It comes (as) no surprise from Indigenous people across Canada that the report has identified MMIWG as a ‘Canadian genocide,’” reads an editorial in Iorì:wase.

Holding the Mohawk Council “to the fire”

As someone “born and bred” in Kahnawake, who was one of the first people on the air at K103.7 in 1981 and has been at his current post for 15 years, Delaronde has experienced the advantages of Indigenous-led media first-hand.

“The media acts as the voice of the people in many ways,” he says.

He calls his community “well-informed,” citing an example of the public meetings of the past where the Knights of Columbus Hall, which seated nearly 350 people, used to be filled to capacity. Now, he says, they see 40 or 50 people at the same kinds of meetings, sometimes less. Why?

“People feel that they’re informed,” Delaronde says, “so they don’t need to be there holding council to the fire.”

Some people, however, aren’t always allowed to be there. Steve Bonspiel was kicked out of a community meeting in 2014 “because they didn’t agree with my opinions,” he says. He’s still not permitted to attend. At a Mohawk Council Candidates Night this past February, local media were told “they didn’t want white guys there,” says Bonspiel. While the entire Iorì:wase staff is Mohawk, one Eastern Door reporter and two radio employees would not have been permitted to attend the meeting. Bonspiel just finished writing a submission saying that what he calls a “ridiculous” rule needs to change.

Despite what might seem like an effort to keep certain reporters at bay, Delaronde values the media’s watchdog role. The public like it when media “grill the council,” he says. “Because, yeah, somebody’s keeping them honest. They appreciate that.”

When something controversial is happening, he says, the media has usually been covering it for weeks beforehand.

“There’s enough of a run-up and commentary in the local media that when a decision finally gets made people now understand,” he says.

Decisions are made easier by this process, he says. “The council makes less mistakes, and I think we’ve learned a lot over time, we’ve learned from our mistakes.”

When mistakes are made, however, local media is vigilant. Delaronde cites a recent housing scandal where local media “sunk their teeth in.”

The story, which Bonspiel said they spent a year investigating, uncovered a fraud scheme within the local social-housing administration. The Eastern Door’s Friday April 12th headline read “Housing bill shoots to $695K missing from books.”

Despite some of these stories being “uncomfortable for a while for some people,” Delaronde sees the thriving local media scene in Kahnawake as a “blessing” and says their loss would be “devastating.”

“We’re so used to it,” he says. “There’s a whole generation of people who have, since they were born, have only known that we’ve had media.”

He attributes the success of local media to a community that’s traditionally very politically motivated, known throughout what he calls “Indian Country” for their activism.

In addition, local media can play an important role in educating the non-Indigenous population, he says, acting as a “training ground of sorts.” Because of the town’s reputation, aspiring or student journalists come here to train. This leads to “a better understanding of what this community means,” he says.

Kahnawake also sends journalists of its own out into mainstream media. Jessica Deer joined the team at CBC Indigenous in the summer of 2018. As a staff reporter for the Eastern Door from 2015 to 2018, Deer covered everything from kinesthetic desks to a satirical fashion show to the plight of ‘60s Scoop Survivors.

Non-Indigenous journalists who spend time in Kahnawake “understand our philosophies a lot more,” Delaronde says, mentioning Montreal Gazette journalist Chris Curtis who made the effort to “get us” when he interned with the Eastern Door in the past.

“We trust him,” he says.

When it’s 2019, not 1920

Back at the office of the Eastern Door, Bonspiel checks his phone. He talks of reporters from mainstream media who don’t make the effort to get them. They call him, several times a week, asking for sources or his take on certain issues.

“I always say, ‘Come to the community,’” he says. “Sit at The Rail and eat some food. Go to a café. There’s places you can hang out. Go to the Magic Palace, go to 207 Steakhouse, and just talk to people.

“Why is it so different here?” he asks. “Why are they so scared to ask our people? Who do we talk to, they say, and, oh my God, where do we start? And, holy shit, can we just go into the community? Of course you can just go into the community,” he says.

“Did you see anybody walking down the street with shotguns killing people?” This is 2019 not 1920, he says.

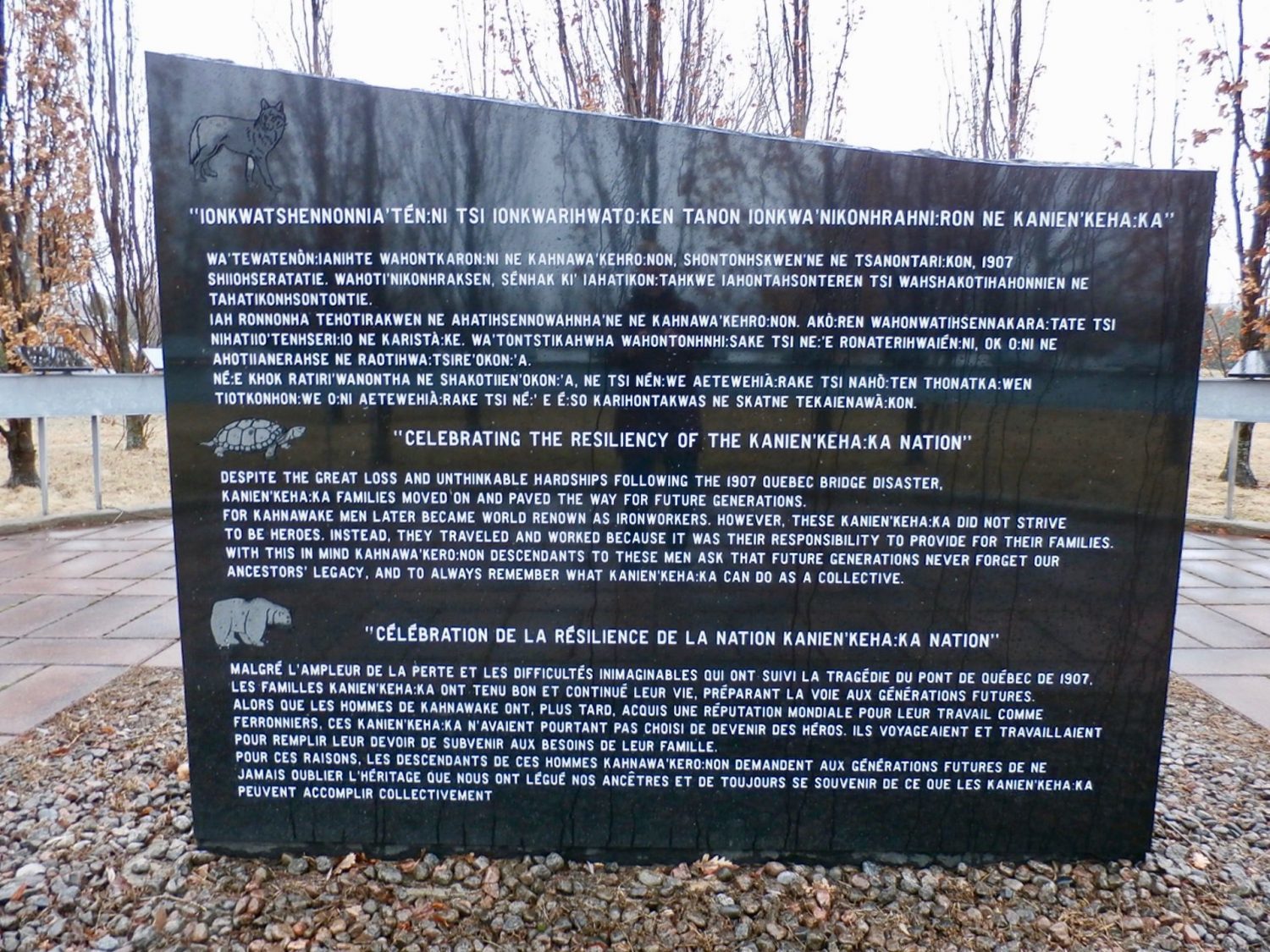

Just past the Bayview Restaurant, where the biggest threat may very well be a giant bowl of fettuccine alfredo followed by a slab of Boston cream cake, a walking path weaves alongside the canal. A memorial for the 1907 Quebec Bridge Disaster, which killed 33 locals, rises against the backdrop of Tekakwitha Island.

Here, the last traces of winter ice float down the narrow channel, merging again with the wide swath of the St. Lawrence. Waves lap against the shore. A bed of reeds blows in the cold wind.

Celebrate “the resiliency of the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation,” the memorial reads. “Always remember what Kanien’kehá:ka can do as a collective.”

Update: This story was updated to clarify two details: first, that the radio station K103.7 is community owned; and second, to specify that Chris Curtis interned at Eastern Door.