Ford’s relationship with the media gave rise to a host of ethical questions.

By H.G. Watson, Associate Editor

There are few media events like ones that involved former Toronto Mayor Rob Ford.

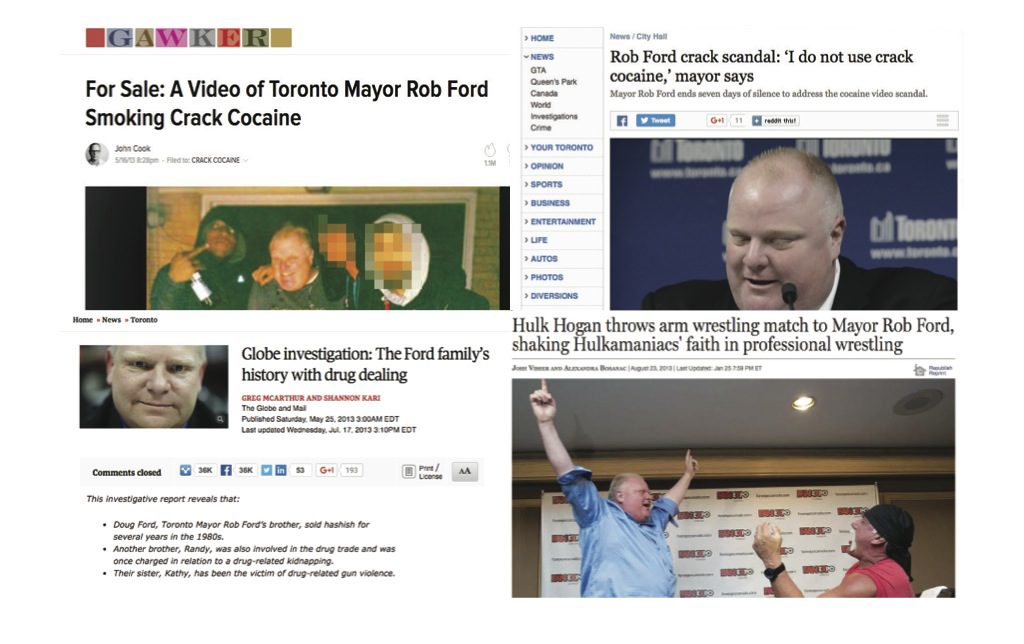

There was the one where, at a hotel just around the corner from comic and sci-fi convention Fan Expo, he arm wrestled Hulk Hogan while people in superhero costumes milled about outside. Or, almost a year later, when Mike Tyson visited Ford’s office and said he was the “best mayor in Toronto’s history.”

Each press conference and scrum seemed more outrageous from the first one he held after news broke of the existence of a video in which he smoked crack-cocaine, to the one months later in which he told reporters: “You asked me a question back in May, and you can repeat that question” and then admitted that he had smoked crack-cocaine.

Ford died on Mar. 22 from pleomorphic liposarcoma, a type of cancer, at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto. His legacy will be debated for a long time to come. But, undeniably, he drew media attention in way that was unlike anything Toronto, or Canada, had seen before, raising questions about how journalists do their jobs.

Recall that, at the outset of the story, the city hall beat was not necessarily the most desirable for a young reporter, according to then-Toronto Star reporter Robyn Doolittle who came to it from the crime beat. “As I envisioned long days of boring committee meetings and agendas and debates about sidewalk widths and tree removal, I boxed up the contents of my office at Police Headquarters and began the grieving process,” she later wrote in Crazy Town, her book about Ford.

But toward the end of Ford’s term, Toronto City Hall was where everyone wanted to be, with international media scrambling to cover the twists and turns Ford’s story took. After Ford returned from rehab and the mayoral election got under way, camera crews camped outside his office, swarming him when he made the quick, barely 12-foot walk from his door to the elevator.

At the centre were Toronto-based reporters. In 2012, Toronto Star reporter Daniel Dale went to city-owned land near Ford’s house in the course of writing about a parcel of land the mayor wanted to buy to expand his own lot. Ford found him outside and accused him of peering over his fence, a claim Dale denied. While later being interviewed by Conrad Black for Vision Television, Ford insinuated that Dale was a pedophile, leading Dale to sue Ford for libel. He later dropped the suit after Ford sent him a two-page apology.

Dale stayed on the city hall beat until early 2015, when he left to become the Star’s Washington correspondent just as the presidential election began to heat up—with a candidate not dissimilar to Ford. Dale recently told Toronto Life that his experience covering Ford made him take Donald Trump seriously as a presidential candidate earlier than other journalists did.

However, the reporter most often associated with covering Ford was then-Star reporter Doolittle. Gawker first broke the news that a video of Ford smoking crack-cocaine existed, the Star went into high-gear to get its own story, the one Doolittle and investigative reporter Kevin Donovan had been working on, out to the public—though calling it an exclusive in the process ruffled a few feathers.

The Toronto Star, and Doolittle, endured months of slams from members of the public who felt they were unfairly maligning the mayor—as well as from Ford and his brother, Doug, themselves. But in Nov. 2013, when then-Toronto police chief Bill Blair announced that police had recovered a video consistent with the one reported by both Gawker and the Star, the tide changed.

The Canadian Press later reported that Ford coverage helped the Toronto Star stabilize fourth-quarter profits in 2014, even if, according to editor Michael Cooke, they lost subscribers. As for Doolittle, she wrote her book, appeared on The Daily Show and eventually took a job as an investigative reporter for the Globe and Mail in April 2014.

The media’s relationship with Ford and his brother provided case study after case study about media ethics. Did libel chill have an impact on why the Star waited to publish the story? Did Ford himself have a case for suing the Star? Did the media treat Ford fairly?

In Jan. 2014, J-Source published the work of Ryerson University students who took on a six-week project looking at some of those very questions. The same students briefly became part of the story themselves—Doug Ford spoke to their class as Rob admitted to using crack-cocaine, according to their professor, Ivor Shapiro.

Would it have been worth it to pay for the video? Some journalists were divided on the topic. Later, in 2014, the Globe paid $10,000 for still photos of the mayor smoking what was described as crack-cocaine. The Canadian Association of Journalists eventually published a report on the topic, advising that the risks involved in paying for photos and videos are high, but that it needs to be looked at on a case-by-case basis.

The Ontario Press Council, after receiving complaints about stories in the Star and the Globe about the Ford family’s history of drug dealings, eventually ruled that both were ethical.

It’s difficult to say definitively what reporters and editors learned from covering the often-times strange and outlandish story of Ford. But as more populist political leaders who share Ford’s penchant for being both folksy and controversial emerge worldwide, journalists will continue to have to ask themselves these same questions.

Perhaps the best lesson to take away is the simplest one. In 2013, a month after Ford admitted his drug use, J-Source ideas editor David McKie noted that one of the lessons had to be how doggedly reporters pursued the story. After all—there would be no Ford story as we know it if it weren’t for the journalists.

H.G. Watson can be reached at hgwatson@j-source.ca or on Twitter.