Award-winning Egyptian-Canadian journalist Mohamed Fahmy, with the help of Carol Shaben, nails the art of pacing.

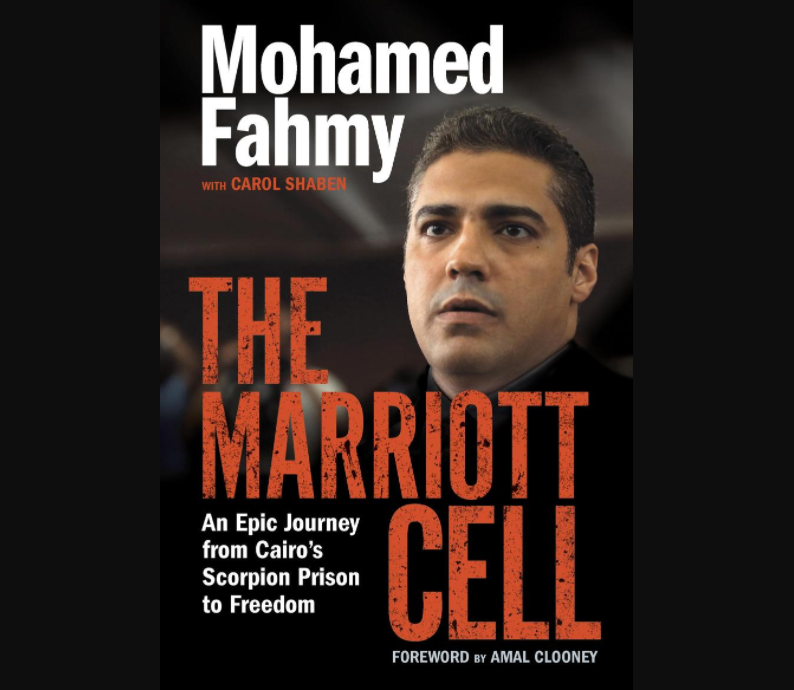

Mohamed Fahmy and Carol Shaben. The Marriott Cell: An Epic Journey from Cairo’s Scorpion Prison to Freedom. Random House Canada, 2016. 432 pages, $34.95.

By Jane Gerster

The Marriott Cell is a gripping, fast-paced read, as one would expect from a story about a journalist in Egypt who suddenly finds himself terrifyingly and wrongfully incarcerated in a notorious prison next to the very people about whom he had been reporting. But it’s worth pausing to recognize how masterful storytelling can add momentum to an already engrossing narrative.

Award-winning Egyptian-Canadian journalist Mohamed Fahmy, with the help of Carol Shaben, nails the art of pacing. The team’s ability to maintain momentum is a rarity among books written by journalists about their experience reporting on — even being caught up in — moments of intense conflict. Too often, such books are engaging and interesting, but squander their momentum by devoting giant chunks of text to providing background detail without any sustaining narrative. Not The Marriott Cell.

Fahmy’s story sets the stakes in the very first paragraph: he’s been arrested. He’s injured, with his arm in a sling, but receives no pity, no special treatment from the guard. These types of moments are ones with which Fahmy is familiar. As a veteran reporter, he got his start in 2003 as an assistant reporter and interpreter for the Los Angeles Times during the war in Iraq. From there, he worked as an assistant reporter and stringer for the New York Times in the UAE. In early 2011, when he flew to Cairo, he was leaving a job in the UAE as a senior producer and manager at a television station.

People, especially journalists, may remember the “Journalism is Not a Crime” campaign in 2014 to press for the release of Fahmy and his three colleagues at Al Jazeera (Fahmy was made bureau chief just months before his arrest). Whole newsrooms posed for photos holding signs saying, “#FreeAJStaff” with tape covering their mouths. But what happened between the day Fahmy arrived in Cairo, just three days before the beginning of Egypt’s Arab Spring, and that day in late December when he was arrested nearly three years later, is revealed slowly over the course of the book.

The Marriot Cell goes back and forth in time, a tactic that works well because of the markedly diverse tones employed to tell the story. In one part, Fahmy is an injured journalist in jail clinging to the naive hope that this is all a mistake and will all be over soon. In the other, he’s an eager journalist who left a well-paying job because he wanted to trade the “opulent, apolitical bubble of the UAE” for “the gritty, real-world journalism I’d grown to love.” He’s in Egypt, home after nearly two decades away. There’s an engaging sense of optimism and purpose in the backstory belied only by the knowledge that Fahmy’s been locked up in Cairo’s notorious Scorpion prison.

Fahmy may have been jailed, but he wasn’t idle. Some of The Marriott Cell’s most absorbing scenes happen in small cells. He turns his considerable gifts as a reporter and investigator on his new surroundings. Fahmy writes notes and letters and Tweets on toilet paper with pens smuggled into the jail, he hides a cell phone on his body in order to tap out messages to his family and his lawyer. Along with his colleagues, Fahmy hosts an evening “radio show,” interviewing fellow inmates who never would have accepted an interview request if not for the fact they were behind bars.

In total, Fahmy spent more than 400 days behind bars. The Marriott Cell is a compelling rendering of that time and the journalism politics he blames for his imprisonment. Fahmy is currently suing Al-Jazeera in Canadian court for $100 million, alleging that negligence on the part of the network ultimately led to his arrest. Fahmy’s thoughts about journalism — why he values it, why he tried to step away from it, why it pulled him back — are sprinkled liberally throughout the book. At times grim and at times inspiring, these small additions make it difficult not to reevaluate one’s own relationship with the profession.

Jane Gerster is a reporter at the Winnipeg Free Press. Her work has appeared in the Toronto Star, the Globe and Mail, Vice, and Makkavik Magazine, among others.