Susan Jose, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, New Canadian Media

The federal government’s Online News Act, also known as Bill C-18, could lead some social media platforms to block Canadian access to news if passed. While Google has already tried limiting news access for some users in Canada in response, critics of the bill worry it neglects smaller media, including ethnic outlets, and fails to provide a sustainable solution for a disrupted industry.

The legislation aims to support Canadian news businesses through compensation from large tech companies such as Google or Facebook — now the beneficiaries of massive advertising revenues — when those platforms share links to Canadian news content. While messaging services are exempt, the platforms will be subject to discussion, mediation, and arbitration in cases when parties can’t reach an agreement.

But Rajinder Saini, president and CEO of Parvasi Media Group, an ethnic media organization based in Mississauga, Ont., said he feels excluded in the discussion surrounding the bill.

“Nobody has approached us so far, and we don’t know how to participate in this debate or conversation or dialogue or whatever,” he said.

Likewise, most ethnic media operate on a smaller scale and usually find it difficult to engage with federal authorities, said Ronny Chowdhury, editor of the Bangla-language newspaper Aaj Kal published in Toronto.

‘Hard to sell’

Google and Meta (Facebook’s parent company) garner no small share of digital advertising revenues “that used to be spent on Canadian publications,” which makes public interest news increasingly difficult to fund, according to a press statement from the office of Pablo Rodriguez, federal Minister of Canadian Heritage who sponsored the bill.

Google and Facebook together accounted for about 79 per cent of the estimated $12.3 billion online advertising revenue in 2021, and just over half of total advertising spending across all media ($17.5 billion), according to a 2022 report from the Global Media and Internet Concentration Project, an effort based out of Carleton University in Ottawa involving more than 50 scholars around the world.

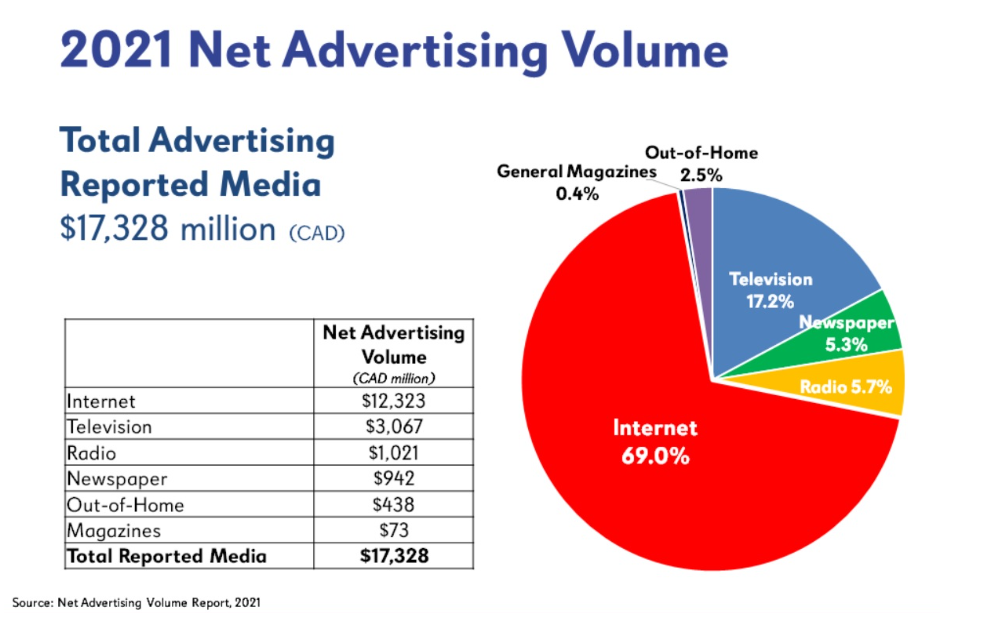

Moreover, internet media had the highest volume of advertising revenue in Canada in 2021 ($12.3 billion), followed by television ($3.1 billion), radio ($1 billion) and newspapers ($942 million), according to News Media Canada, an advocacy group for print and digital media.

With its continued growth, internet advertising had the highest net advertising volume in Canada in 2021. (Source: nmc-mic.ca)

The appeal of online media isn’t lost on Saini, who said his company has converted one of its print newspapers to a web publication.

“Online is very popular, there is no question about that,” he says. “But in ethnic communities, it is very hard to sell (digital ads).”

Saini said it costs about $10,000 per month to pay four employees to run one of his websites, The Canadian Parvasi, which only generates about $200 per month in advertising revenue through Google’s AdSense program for publishers. While Google pays publishers to feature ads on their websites, it also receives payment from advertisers via a program called Google Ads. Similar models are in place for platforms of other tech giants.

“Even if the website does very well, I may get $400 to $500 per month,” Saini says. “But will that eventually serve the purpose (of sustaining the website)? No.”

The survival of journalism

Micheal Geist, a University of Ottawa professor and Canada Research Chair in internet law, is calling out the bill for widening the gap between smaller media players and big conglomerates.

According to Geist, the effects of tech companies blocking news media would be felt most dramatically by independent and smaller ethnic media outlets, which often depend on social media or discovery by search engines to generate greater web traffic.

“For the big players, Google searches or Facebook is relatively unimportant. They’ve already got larger audiences,” Geist said. “Yes, it would be a loss to them, but it’s not going to threaten their existence.”

Having tech companies pay publishers for posting or linking to their news content challenges the basic concept of capitalism, said Victor Ho, retired editor-in-chief of Sing Tao Daily, a Canadian Chinese-language news outlet.

“News content on platforms such as Google and Facebook benefits both the platform as well as the news organizations,” Ho said. “The news reaches more people through online channels. It is a win-win situation.”

While Ho sees value in the intention of supporting Canadian media through Bill C-18, he’s also convinced that its mechanism for compensating news businesses isn’t a sustainable solution to help traditional news media to thrive in a digitized world.

Rather, he adds, any solution or bill needs to consider journalism’s survival as audiences turn to advancing technology such as artificial intelligence for information, Ho said, referring to developments such as the popular AI chatbot ChatGPT.

What’s more, the media industry has been disrupted with technology and digital advancement, and Bill C-18 won’t fix the current ecosystem, Ho said. As a result, news outlets will continue to fold, allowing other players with ideological agendas to fill the void with propaganda.

Call for better reforms

Ho said Bill C-18 is trying to protect a traditional model of news media, but a consensus should be reached on how to make a modern model work.

An alternative could see Google and Facebook contributing some percentage of their Canadian-based ad revenue towards a fund for journalism, Geist says.

“That takes away the issue of paying directly for (news) links … because what you’re funding is journalism,” he explained.

On the other hand, ethnic media could benefit with larger revenues earned via corporate and government ads, Chowdhury said.

“If there is a channel that could connect us to (those advertisers) so that we can show our target audience — make them understand our reach — it would potentially benefit us,” he said.

Saini, too, felt that government-issued advertisements for ethnic media would be a sustainable model for financial support.

“The federal government is giving advertisements aimed towards immigrants to mainstream media,” Saini said, adding that ads for English language classes, for example, may be better directed to ethnic media audiences. “You will only listen to these news items if you already understand English,” Saini says.

However, Rodriguez’s office was careful to note that government assistance isn’t a silver bullet for the industry’s problems.

“Existing initiatives like the Local Journalism Initiative, which allows news media in underserved communities to hire journalists, have helped stabilize several news organizations,” reads the statement, referring to another program funded by the Canadian government. “But direct government support alone will not solve the fundamental problem affecting the health of the news media today.”