From poorly watched propaganda channels to public office-journalist relations, we’ve got a few things in common.

By Sean Holman

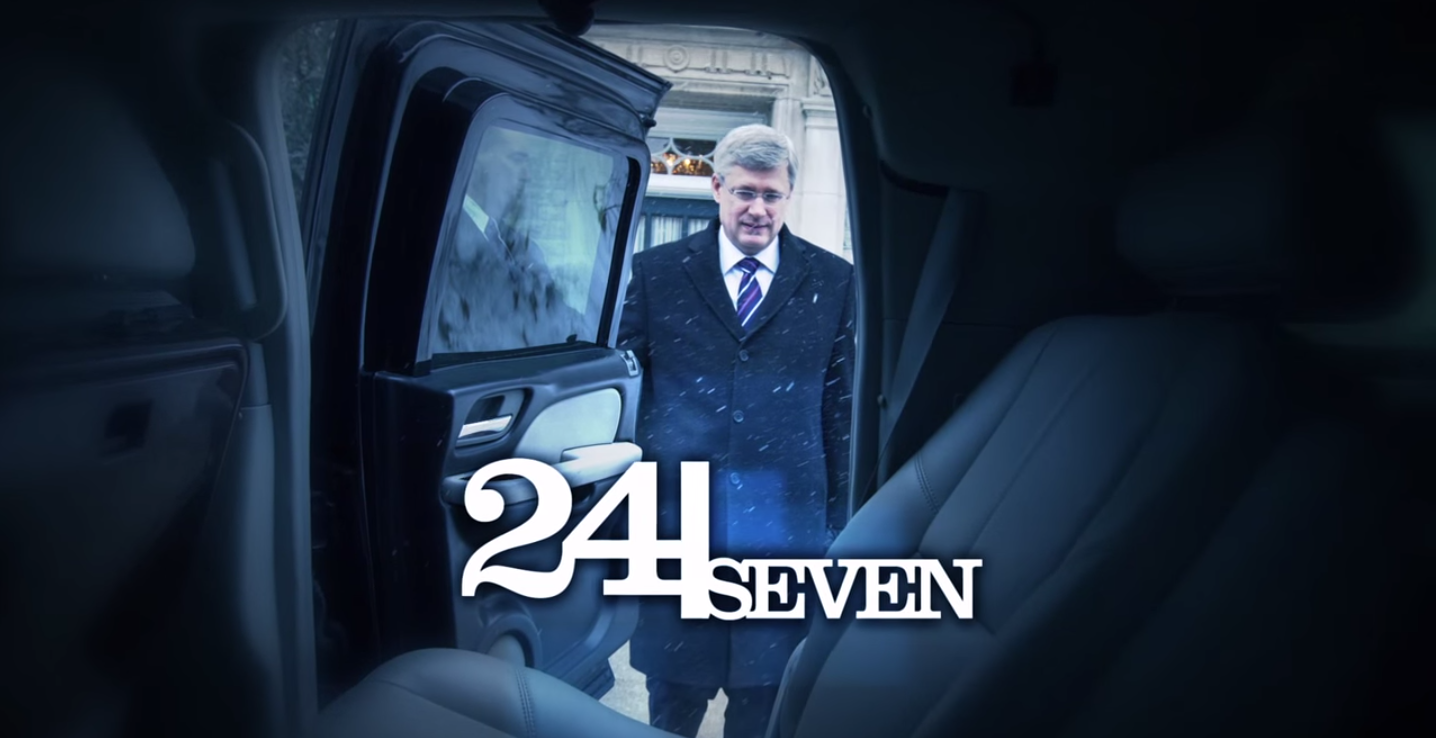

Stephen Harper’s taxpayer-funded 24 Seven Internet infomercial has been ridiculed for its minuscule audience. But the prime minister can take comfort in the fact a similar weekly program produced by United States President Barack Obama’s White House doesn’t seem to do much better with viewers.

24 Seven was launched just over a year ago to propagandize Harper’s accomplishments. Three bureaucrats in the Privy Council Office are usually responsible for producing that program, which—between Jan. 2, 2014, and Jan. 1, 2015—received an average of 2,592 YouTube views per episode as of this past Saturday.

That may seem small, working out to 7.3 views per 100,000 people in Canada. But, over a similar period, Obama’s West Wing Week received just 7.8 views per 100,000 people in the United States.

DEAFENING SILENCE

Last week, the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Public Integrity launched a new blog to shine a light on how often public officials refuse to answer questions from journalists—something that has “lately” become a problem in that country. But, even in a smaller country such as Canada, recording those refusals would be a voluminous task.

A search of newspapers in the Canadian Newsstand database shows that between Monday and Friday last week, journalists reported at least 24 instances of public officials not responding to questions or being unavailable to answer them. Those instances include:

• Aboriginal Affairs Minister Bernard Valcourt’s office not answering specific questions from the Canadian Press about a contract to come up with different ways of providing a food subsidy for northerners;

• Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne’s office not responding to a request for comment from The Globe and Mail about a decision to refuse the City of Toronto’s request for financial relief;

• Alberta Health Minister Stephen Mandel not responding to a request for comment from the Calgary Herald about a decision to shelve the building of a new cancer centre in Calgary;

• B.C. Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations Minister Steve Thomson being unavailable to answer questions from the Times Colonist about a decision to allow “hunting guides and their foreign clients a larger share of wildlife across the province” and

• B.C. Mines Minister Bill Bennett not being reachable by the Globe for comment on the upcoming release of a report into what caused the collapse of a tailings pond at the Mount Polley Mine.

CENTRAL QUESTIONS

The blame for the federal government’s non-answers to reporters could have less to do with “department media relations officers and more the result of centralized message-control by the Privy Council Office, the bureaucratic arm of the Prime Minister’s Office.”

That analysis, which was penned by CBC News’s Kady O’Malley earlier this month, might leave Canadians thinking that, without such centralization, reporters would start getting real responses from the government. But in my estimation, that’s extremely unlikely likely.

Overly broad, boilerplate answers are also provided by local and provincial governments across Canada, as well as corporations and non-governmental organizations.

I got them for nine years as a reporter covering the British Columbia government, whose Public Affairs Bureau was jokingly known for serving PABlum to journalists. I also cooked up some of that PABlum myself as a communications adviser for the province’s Liberal and New Democrat administrations. Let me assure you: it wasn’t the bureaucratic arm of the Prime Minister’s Office that was behind that boilerplate.

Nor are such talking points and message boxes peculiar to Canada.

In a recent letter to Obama, 48 American journalism and open government groups complained that journalists are now getting “written responses of slick non-answers” rather than being allowed to communicate with federal government employees. Appropriately, White House press secretary Josh Earnest responded to those complains with his own non-answer, which failed to directly address the groups’ concerns.

Such public relations tactics threaten the public’s right to know. But no mere change in government, in this country or in the United States, will stop their deployment. They’ve become an embedded part of our political system—something that has just as much to do with departmental media relations officers as it does with centralization of that system.

[node:related]

FOI NEWS (FEDERAL)

• The Tyee reports a government “briefing on proposed anti-terror legislation was light on information and heavy on restrictions,” prompting protests from parliamentary reporters.

• According to the Globe, planners and researchers say, “The cancellation of the mandatory long-form census has damaged research in key areas, from how immigrants are doing in the labour market to how the middle class is faring, while making it more difficult for cities to ensure taxpayer dollars are being spent wisely.”

• The Ottawa Citizen reports, “The federal government has spent approximately $57 million on outside consultants over the past nine years to help decide which government records Canadians are allowed to obtain.”

• Information Commissioner Suzanne Legault is concerned Bill C-520 may have an impact on her ability to “recruit and retain the best and brightest.” That private member’s bill, which was introduced by Conservative MP Mark Adler, would require anyone working for or applying to work for an agent of Parliament to publicly disclose if they have held a politically partisan position in the last 10 years. Those agents include Legault, as well as Canada’s auditor general and its chief electoral officer. According to the information commissioner, that disclosure “could be used to assert the existence of a possible bias in the conduct of an investigation or audit” by her office. (Hat tip: BC Freedom of Information and Privacy Association.)

FOI NEWS (PROVINCIAL)

• According to Borden Ladner Gervais LLP counsel and privacy law expert Barbara McIsaac, “two recent decisions from the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario provide some guidance” about when aggregated or anonymized information can be released under the province’s access law.

FOI NEWS (LOCAL)

• In his most recent report on Ontario’s open meetings law, ombudsman André Marin has once again criticized its lack of teeth. The law, which was passed in 2008, requires municipalities to hold most of their meetings in public. But there’s no penalty for not following that rule. Moreover, just 196 of Ontario’s 444 municipalities choose to use the ombudsman’s free services to investigate open meetings law complaints. By comparison, “134 municipalities use Amberley Gavel, under contract with Local Authority Services, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Association of Municipalities of Ontario, an organization which promotes municipal interests.”

• The Record’s Luisa D’Amato writes that Waterloo, Ont., residents “love the idea of their city as being innovative, efficient and businesslike.” But after an “ill-advised decision” to “limit questions from elected officials, and cut down on public access to discussion on the city’s budget,” those residents have learned that being businesslike is “not as important as openness and public scrutiny.”

• The code of conduct for Waterloo city councillors means that one of them had to “seek a majority vote for council for detailed answers on budget questions.” The Record quotes Mayor Dave Jaworsky defending that code, saying, “[If] you want council or the board as a whole to function as one…you can’t have one person instructing staff to do work.”

• “A record number of access to information requests at [Waterloo] city hall last year may mean more staff could be required to handle the extra workload in the future,” according to the Waterloo Chronicle. The newspaper reports, “The majority of the requests are related to searches for private property information and staff believe the increase is partially driven by the city’s rental housing bylaw, passed in 2011. Under the program, landlords must apply for a licence and renew it annually by April 1. If a rental property sells, the new owner must apply for a new licence, which includes getting all the necessary documentation and inspections.”

• Neal Yonson, who contributes to a website covering the University of British Columbia, tweets, “Sigh. I want to like UBC’s FOI people, I really do. Delaying 60 days to send an $800+ fee estimate is not how we become friends.”

[[{“fid”:”3587″,”view_mode”:”default”,”fields”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:””},”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”attributes”:{“height”:”3776″,”width”:”2555″,”style”:”width: 100px; height: 148px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px; float: left;”,”class”:”media-element file-default”}}]]Sean Holman writes The Unknowable Country column, which looks at politics, democracy and journalism. He is a journalism professor at Mount Royal University, in Calgary, an award-winning investigative reporter and director of the documentary Whipped: the secret world of party discipline. Have a news tip about the state of democracy, openness and accountability in Canada? You can email him at this address.