In newly reopened Kamloops, B.C., an afternoon spent selling street newspapers is a slow one.

Pre-pandemic, The Big Edition vendor Leo says he would have made $200 a month handing out the paper. He’s now raking in around $50 in the same period. He’s found relative luck distributing copies around residential streets, where he finds familiar faces spending their days in their gardens, “pruning their fruit trees,” and otherwise sheltering in place.

But his usual distribution spots are no longer fruitful. The downtown core of Kamloops, once bustling with foot traffic, is now mostly barren (“It’s like there’s tumbleweeds going down the street,” Leo says.) And the churches outside of which he once set up shop are no longer open for in-person worship; pre-pandemic, he found success in catching people immediately before and after Sunday morning service, while they were “feeling, you know, love your neighbour and all that kinda stuff,” he says.

The Kamloops street paper only recently restarted its vendor distribution services as B.C. began testing the waters of reopening in phases after two months of COVID-19 lockdown. Like all street papers in Canada — one of four within the International Network of Street Papers (INSP) — written and distributed primarily by homeless, precariously housed and low-income community members, The Big Edition made the wrenching decision to stop sales on the street mid-March.

Albeit necessary to guarantee their safety amid a global pandemic, the decision to cease print distribution left vendors at Canada’s street papers — also in Vancouver (Megaphone Magazine), Edmonton (Alberta Street News), and Montreal (L’Itinéraire) — without a crucial source of income. Treated as independent contractors, vendors buy copies of the paper from their editors on a wholesale basis for a low cost — around 50 cents per copy — which they then distribute to the public on a pay-what-you-can basis (a minimum donation of a few dollars is often suggested.) They keep all profits they earn from these sales.

While all four street papers continued publishing online content throughout COVID-19 lockdown, they were mostly forced to halt the presses, with rare exception (The Big Edition, for example, continued selling papers in bulk to large clients, like real estate management companies, who placed them in stands in the lobbies of buildings they rent). And while some have begun distributing in-person again, vendors and editors alike fear it may be a while before readership returns to its typical levels. Any anti-homelessness stigma vendors faced before COVID-19 is now compounded by widespread fear of physical touch and a collective tightening of purse strings in response to a severe and extended economic decline.

Leo remains hopeful that incoming warm weather will make things easier, though. For almost three months, he’s had to get creative about finding alternative sources of income, turning to busking and hauling jobs. Alberta Street News writer-vendor Vivian Risby has had to do the same — she’s spent her days collecting used bottles to return to retailers for small cash deposits while paper sales were on pause.

While Risby says she was scared of catching the virus through distribution, among other activities that could’ve placed her at risk, she was reliant upon the income. Not having cash from paper sales coming in regularly has been difficult.

“That’s my work,” Risby says. She also hopes to start contributing to the paper again soon, but with libraries closed, finding a stable internet connection has proven challenging. She has one story in the works, which she’s writing by hand and plans to submit on paper.

Her editor-in-chief, Linda Dumont, has continued collecting these pieces and publishing them online while in-person distribution is shuttered. But Dumont says she worries about the financial bind COVID-19 has put vendors like Risby in.

As sole head of the paper, Dumont has kept it afloat without taking pay (on top of her full-time job) for almost two decades. And while that comes with its obstacles, few have proven as difficult as this pandemic: Dumont was among the first to be laid off in March when gyms and fitness centres shut down. She had been putting a portion of her own income into printing the Alberta Street News, but when her salary disappeared, she resigned to the fact that she had no option but to temporarily cease printing.

“If I can’t afford it, I just realized I can’t do it, and that’s it,” Dumont says. “If you can’t do it you can’t do it.”

While print copies are currently out of commission, Dumont adds that it’s important to her to continue offering her writers a place for their work. She says halting publishing altogether was never an option: “Quitting, you can’t just do that to people. Because people, they depend on you for support.

“It’s so important for the writers to continue to write the stories and to feel good about writing their stories,” Dumont says. “If I don’t publish they don’t have that outlet, and especially when they’re stuck at home like this, it’s even more important that they have that outlet.”

She has also continued to check in with her vendors by phone and at nightly soup kitchen service at the Refuge Mission Hall, where she volunteers.

In Montreal, Luc Desjardins, editor-in-chief of L’Itinéraire, has been doing the same. He’s kept his team of 14 staff busy calling their roughly 200 vendors every day to ensure their well-being and offer financial and medical support where needed.

A relatively large operation that also includes a café, L’Itinéraire has been well-poised to protect vendors as its province experiences the highest rates of COVID-19 in the country, undoubtedly putting Montreal’s vulnerable populations — primarily low-income, Indigenous and residents of colour — at the greatest risk.

For years, the magazine has offered aid to its vendors in finding and maintaining affordable housing — something many fear losing without widespread rent freezes and protection from eviction. Desjardins says they’re still doing this work, even as the city’s lockdown continues.

“We follow our vendors through all the process, and make sure that they pay rent, and they receive the money from the government to pay the rent,” Desjardins explains.

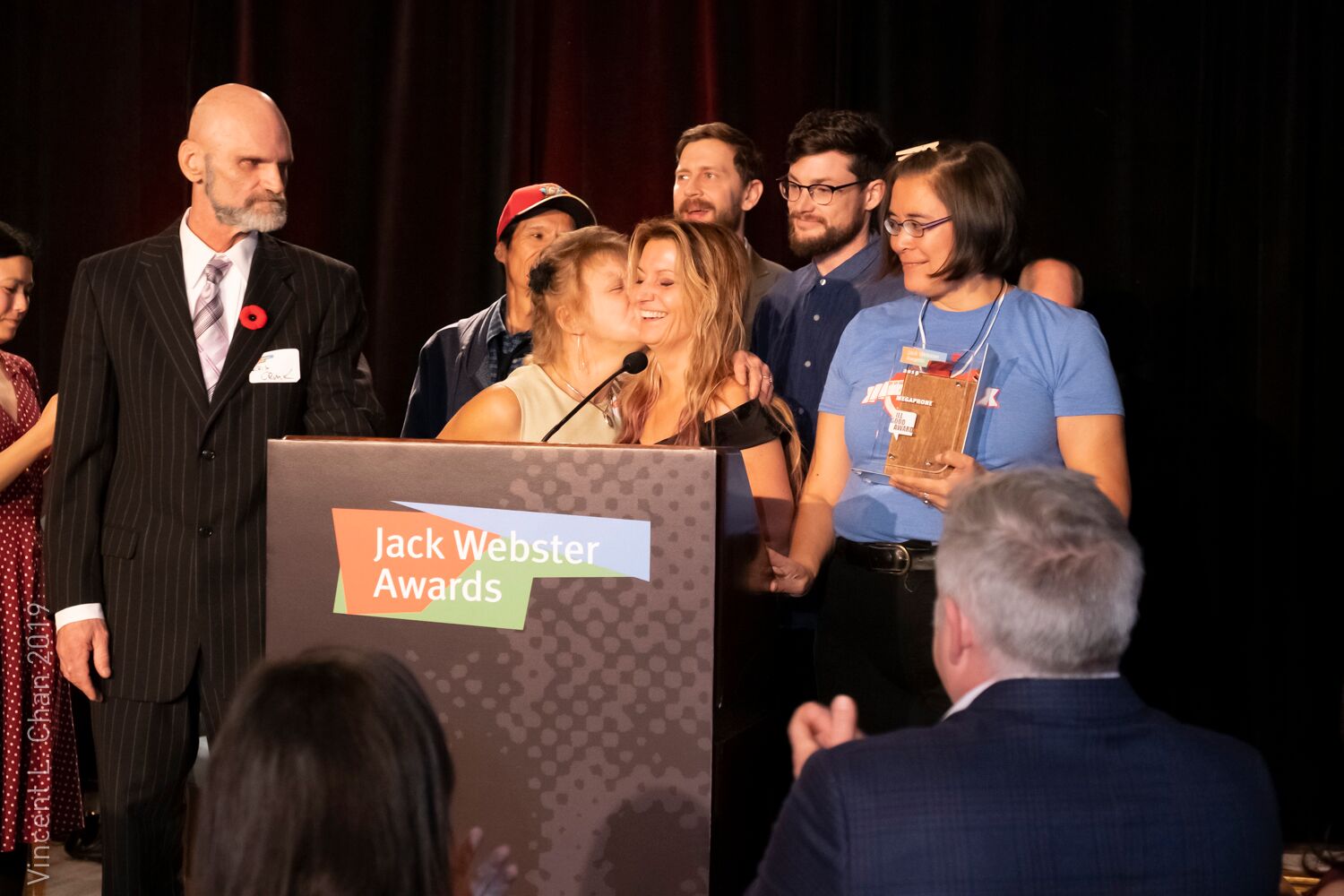

The magazine’s leadership has also released $40,000 in emergency funding and grocery gift cards to help vendors fund the basics while they are without income from paper distribution. Meanwhile, in Vancouver, staff at Megaphone have worked around the clock to secure additional funding for vendors through fundraising drives, publishing grants, and citywide aid. They also moved quickly to add a page to their website to facilitate online magazine sales midway through March, as soon as lockdown orders came into place. Julia Aoki, the magazine’s executive director, says she’s “relatively confident” that online donation levels, as a result, have been on par with what they were pre-pandemic (though Megaphone and other street papers typically don’t collect data on donation levels because vendors, who keep all of their profits, are not required to report what they make).

Israel Bayer, director of INSP North America, says Desjardins and Aoki are far from alone in their overtime efforts to support vendors financially through difficult times. In parts of the United States, he’s seen papers with the available funds release as much as $100,000 in vendor support, while banding together with smaller papers to share resources and tools. This agility through unprecedented widespread challenge is promising, Bayer says — but it’s in no way surprising.

“Street papers are extremely resilient,” he says. “We’re nimble. Street papers existed in an already irrational environment pre-COVID. Knowing that homelessness itself is not rational, and that people were already experiencing dangers and health concerns and people dying on the streets … in many ways we’ve just shifted our priorities.”

Among Bayer’s current priorities is preparing for the likely incident of a second wave of COVID-19 throughout North America. He hopes the lessons editors at street papers have learned through the first wave can serve as preparation for another one.

But before that can happen, a number of papers are looking critically at what it will mean to restart distribution of hard copies in a new, socially distanced normal. Street paper sales is a game that depends upon readers forging unique, authentic connections with their local vendors: running into the same friendly face at the same corner on your walk to or from work every day, around the same time, offers readers a sense of routine and rapport, which many vendors rely upon to get their papers sold. But those connections are tested from two metres away.

“What gets [people] to take the papers is the fact that they’re putting money directly into some recognizable person’s pocket,” Alex McGilvery, layout editor of Kamloops’ The Big Edition says. Under new socially distanced conditions, friendly faces, behind masks, are no longer recognizable, and online sales are a tough replacement.

Desjardins, Aoki, Dumont, and McGilvery all say they fear, in one way or another, that their vendors will have difficulty getting papers in the hands of readers in a world where touching is taboo and proximity is prohibited. Desjardins even contacted health experts to find out the likelihood of virus transmission through magazine paper: The odds are slim, he says, but that doesn’t guarantee that L’Itinéraire readers won’t be afraid. “We have to think about how people [are] going to see us, interpret us,” Desjardins says.

Aoki notes that any fear around virus transmission is rightfully a two-way street. Many of Megaphone’s vendors have pre-existing health conditions that make them uniquely vulnerable to COVID-19, she says — so helping them feel safe delivering papers in-person will be a process of “reacclimation.” The paper plans to equip all vendors with hand sanitizer as a starting point, and hopes contactless purchases through their donation app can help fill in gaps. (She notes that Megaphone saw a spike in app donations at the start of the pandemic, but as time went on, “giving fatigue” set in for many Canadians. “That’s really what keeps me up at night,” she says.)

Meanwhile, Dumont says her vendors have toyed around with various touch-free systems for money collection: One vendor has a bucket she sets a few feet away from her, into which Alberta Street News buyers can drop cash. Leo plans to do the same with his sales of The Big Edition in Kamloops — it’s a trick he says he picked up from busking, where dropping tips into a hat or a guitar case is the norm. “You throw money at me, we don’t have to touch, and then I’ll just have the paper stacked over to one side,” he says. “You know, ‘help yourself.’”

While The Big Edition has yet to create an online platform for donations and sales transactions like its counterparts in Vancouver and Montreal, Leo adds that virtual payments are far from ideal for the vendors most street papers employ, regardless. “Cash is still king among the poor,” he says. (Some street papers, like Megaphone, are set up to handle this: vendors can collect payments digitally through the magazine’s app, then collect their earnings in cash in-person at the editorial office).

But regardless of collection method, asking readers for cash requires that they have bills to dole out in the first place. As a growing number of restaurants and retail shops shift away from cash in an effort to reduce the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission between staff and customers, fewer and fewer Canadians are carrying it with them. This broader shift in societal norms around payment could leave street papers behind.

“Prior to COVID-19 we were already moving toward a cashless society, which presents a huge problem for people who rely on those extra dollars to survive,” says Emily Mathieu, former affordable housing reporter at the Toronto Star. She predicts that a post-COVID world will largely be a cashless one, and street papers will have to get creative to keep up.

She notes that any challenge the diminishing use of cash poses to vendors will be coupled by general hardship print journalism is already facing across the whole of Canada’s media landscape. Street papers are not immune to the decline of print news, of course, and some have long since questioned how sustainable the business model is in a world now dominated by digital media.

Mathieu says in her own reporting on housing, she relied primarily upon podcasts (like Crackdown, on Canada’s overdose crisis, or Out of the Blue, on housing and homelessness) and e-newsletters (like Homeless News by Haven Toronto, a drop-in centre for housing insecure and socially isolated men). Like street papers, these forms of digital media have developed loyal, niche audiences, and are well-regarded for their willingness to hand the microphone over to communities with lived experience that are otherwise marginalized by mainstream news media.

“They’ve created this platform where they can elevate those voices in a way that allows them to have the authority that they deserve,” Mathieu says.

Street newspapers — which offer exclusive reporting on issues affecting homeless communities, possible primarily because of their unique proximity to the issues — accomplish the same goal. Many also offer e-newsletters and podcasts of their own, including Megaphone, which has also hosted online Q-and-As about homelessness and the Canadian incarceration system during COVID-19 lockdown.

In theory, these sources of news should be able to coexist — not compete — in a media landscape with a long history of getting homelessness wrong. The 2011 paper “Framing Homelessness for the Canadian Public: The News Media and Homelessness” published in the Canadian Journal of Urban Research found that the majority of stories position unhoused communities as “deviant,” “dependent,” or “other,” focusing on crime, conflict, or a reliance on social support systems within these communities. Reporting like this “fortifies the boundaries between ‘us’ and ‘them,’” the authors write.

They go on to argue that because the majority of North American journalists come from relatively affluent backgrounds, and thus have no lived experience with homelessness, they’re likely to display loyalty to the systems that have privileged them, in turn neglecting to give income inequality and its causes the nuanced criticism that they deserve.

Similar to podcasts such as Out of the Blue, and newsletters such as Homeless News, street papers set out to fix a long legacy of reporting on marginalization in the third person. “It’s important not for us to speak on behalf of, but to provide a means for people to speak for themselves,” Aoki says of Megaphone’s work.

They play an invaluable role in our media landscape as such, informing the work of social justice and equity reporters whose words have larger mainstream reach. Among those reporters is Katie Hyslop, education, youth and social justice reporter at B.C.’s The Tyee, who says Megaphone offers “the most consistent reporting from the point of view of people who are low income or living without housing,” that she draws from for her own work. (Disclosure: Hyslop worked at Megaphone from 2011 to 2016).

But printed papers have been shuttering across the country for decades now, and COVID-19 only places additional pressure on a media form already under strain. Digital media may have better chances of surviving, Mathieu posits, so the trick for street papers will be figuring out how to pivot (and in a way that keeps vendors paid without requiring that they set up bank accounts with hefty fees).

It’s a challenge most are up for, though — if anything, this period has given editors the chance to rejig their websites, work out the kinks of their app-based payment systems and secure additional emergency funding where needed. “Being nimble, being able to survive in this world that is not rational also provides us the opportunity to be stronger than ever,” Bayer says.

He remains firm that street papers will continue to survive even as legacy media across North America drastically reduce their print offerings. In part, it’s because their readership is driven by a range of motivations: while traditional news media readers buy papers primarily in the interest of news consumption, readers of street papers do so not just for an interest in news on housing, but also out of interest in philanthropy and a desire to support the vendors they’ve cultivated close, face-to-face relationships with.

“On one side there’s the media aspect and on the other side there’s the social entrepreneurial side of things,” Bayer says. “Due to the relationship [between] readers and people on the street, we don’t expect that we’re going to face the decline in a way that other major media outlets are.”

He also notes that economic inequality is only slated to rise as a result of COVID-19, and homelessness is predicted to increase by 45 per cent. A post-pandemic world may be one where touch is taboo, but it will also be one where street papers (and the news they provide, both by and for unhoused communities) are more essential than ever.

“We’re seeing every inequity that exists around people of colour, racism, immigration, the criminal justice system, I mean, everything right now is on full display,” Bayer says. “We’re expecting a tidal wave of people to hit the streets. And so we’re going to have to adjust to a new reality.”

In the meantime, vendors like Leo await safer conditions and heavier foot traffic. He’s sure that this work will continue to require him to pivot, but he’s up for the task. “If anyone can do it,” he says, “it’s … homeless people.

“We’re used to having plan X,” he continues. “You know, like ‘plan A, that didn’t work, how about plan B? Oh, guess not.’ You get pretty creative.”

Editor’s note: This article originally described Julia Aoki’s title as editor-in-chief of Megaphone and was corrected on July 16, 2020 to reflect her position as executive director.