By Mitchell Thompson

Mark Latham says the cure for local media’s ills is voter-funded media—where voters decide which media outlets receive grants.

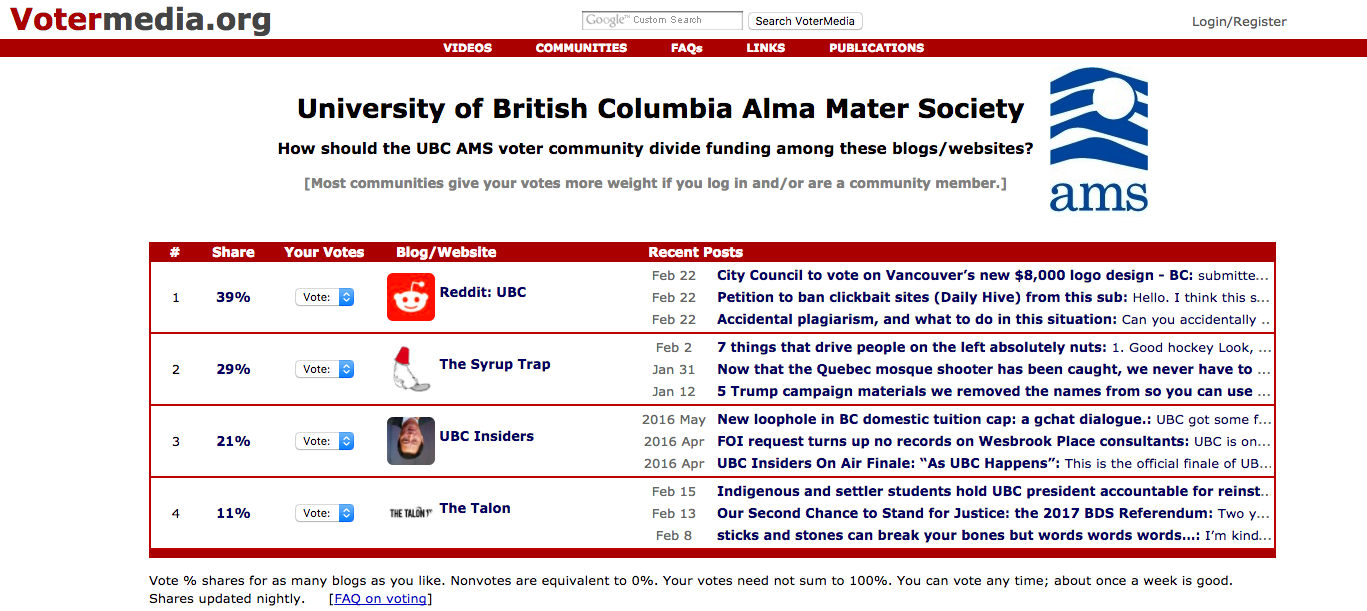

The economist and Votermedia.org founder says the University of British Columbia has been providing grants to media outlets covering the school’s student union and its elections since 2007. It allows voters to rank their prefered outlets to receive grants at the end of the ballot. In 2007, there were eight prizes to choose from, with the highest being $1500 and the lowest being $500. Latham says in his report “after the sections for voting on the President and other executive positions, the media contestants were listed with a box next to each, and voters could check any number of those boxes to indicate their support for awards. The contestant with the most votes got first prize, and so on.” Latham says any individual, media outlet or group can enter, provided they pay the $100 entrance fee, with 13 entering the first year.

In October, Latham presented the findings of his ongoing experiment at UBC to the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage. He argued voter-funded media, as pioneered at UBC, could be adapted to support local media covering municipal politics.

He says since municipal politics in small and mid-sized cities are usually “neglected by existing media,” and given the low cost of blogging, cities “can expect (a) significant improvement in coverage of city council meetings, policies and elections from as little as $20,000 to $40,000 of annual voter funded competition.”

J-Source reached out to Latham to ask him about his experience with the committee, voter-funded media at UBC, and how it could be extended.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

J-Source: How does your consensus voting model eliminate some of the problems of subsidizing news?

Mark Latham: It’s a vote on which media outlets did the best job.

It’s a consensus decision process, where the media supported by the largest number of voters will win the first the prize. The first time we had eight prizes and 13 media outlets entered. The top eight vote-getters got the top prizes. We eventually developed a system whereby voters could determine how much goes to each outlet.

Consensus voting means if you appeal to less than five per cent, then you basically get nothing. t requires that you appeal to the widest base, very much like in municipal politics, where there may be various projects up for a vote but each is only accepted if the majority voters say yes.

That’s best for me, as an economist. If we are trying to support public benefit, it’s reasonable to use public funds, but only if a large percentage of voters support it.

J-Source: How is the funding determined, exactly?

ML: You get voters to say a number.If one says $100, one says $5,000 and one says $0 and you take the average, the voter has an incentive to go to extremes. Instead, if you take the median, there is no incentive to go to extremes—a vote can only pull it down by one vote regardless of how high or low you go. If the median is $5,000, that means 50 per cent voted for more than that and 50 per cent voted for less. So if you modified it to, “should we give them $5,000 or $6,000?” you would get 50 per cent saying $5,000, since they voted for less. These are steps I went through to work out the consensus-algorithm behind voter-funded media.

Then, we shifted that to fit the set budget and calculated it by per cent of the budget and then, overtime, per cent of the flow, since the funding isn’t a one-time lump-sum.

J-Source: What qualitative effect did this have on the student run media at UBC? Would that be the same at a municipal or national level?

ML: Based on the UBC example, it takes a few election cycles for it to catch on. The first year, voters, to many people’s surprise, didn’t vote for the best media. A lot of it depended on having name recognition the first time. But, the second year in, it came second and since then, it’s been the winner and has been the highest quality journalism and I think anyone looking at them would agree.

Generally, I think if we have a system that supports more intelligent information that actually serves the public, it doesn’t take long for voters to realize that.

J-Source: How did it change the election cycle at UBC?

ML: We saw an increase in the quality of the candidates pretty immediately at UBC. People from other media outlets said this is because they had to work harder because there was more media coverage. Even the head of UBC’s competitor student paper said this is because voter media is running circles around it in election coverage.

J-Source: Did student engagement increase at UBC?

ML: Before I pitched voter media, in January 2006, I watched UBC’s All Candidates Meeting in a big theatre and, aside from the MC and two other people, the room was empty.

Later, when the voter media were there— grilling the candidates and reporting— more students showed up to find out what the candidates were like and how they should vote. And, in the years since, those theatres have been less empty and the media there is asking tougher questions.

J-Source: If this were applied elsewhere, how might that change voter behavior?

ML: It could cut down on the sort of populist rebellions we’ve been seeing. The reason we get Brexit and this populism is because the systems we have in place have not been functioning well.

We all know there are serious problems with journalism and it is not, speaking as an economist, the journalists’ fault. It’s because we don’t pay you folks the way we should to serve the public. Some of you will do it anyway, whether you are paid well for it or not, but that’s no way to run a journalism business, let alone, have a career.

J-Source: So, it would cut down on populist backlash?

ML: Voter-funded media might create a more intelligent backlash.

[[{“fid”:”7288″,”view_mode”:”default”,”fields”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:false,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:false},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“1”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:false,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:false}},”link_text”:null,”attributes”:{“height”:300,”width”:300,”style”:”width: 100px; height: 100px; margin-left: 5px; margin-right: 5px; float: left;”,”class”:”media-element file-default”,”data-delta”:”1″}}]]Mitchell Thompson is a third-year journalism student at Ryerson. He is also the ideas co-editor for Folio and a contributor at Disinformation. He has previously written for Rabble, Canadian Dimension, Dissident Voice and others.