April Lindgren is a professor at the School of Journalism at Toronto Metropolitan University and principal investigator for the Local News Research Project.

Expressions of shock, concern and loss were widespread recently after Postmedia Network Canada Corp. and Torstar Corp. announced a newspaper swap and the closing of three dozen publications.

Local politicians worried aloud about who would keep them honest and citizens informed. Business owners fretted about the loss of an affordable advertising option. Citizens took to social media to mourn the closings.

The angst is consistent with research that suggests Canadians value local news: Sixy-nine per cent of respondents in a recent poll said they would consider it a “very serious” consequence if the decline in news organizations resulted in less local reporting. Ninety-two per cent said news about their communities is either very important (45 per cent) or somewhat important (47 per cent).

This love affair, however, isn’t quite what it seems.

Unwilling to pay for it

There’s a significant disconnect between the value Canadians say they place on local news and their willingness to actually pay for it.

Torstar’s announcement last January that it was closing the Guelph Mercury prompted devotees to shed tears, hug the building that housed the 149-year-old daily and wallpaper the Mercury’s front door with sticky notes bearing farewell messages. Yet only 22 per cent of Canadians have print or digital newspaper subscriptions.

More chilling was an Abacus poll released in June that suggests the majority of people are blasé about newspaper closings: Eighty-six per cent of respondents said they will still get the news they need if their local daily goes out of business.

The results were consistent across regions, age groups, among men and women, political party supporters, urban and rural respondents, homeowners and renters.

“Even among those who only have one newspaper in their community, 84 per cent think they would still be able to get the news they feel they need,” the pollsters noted.

What all of these contradictions point to, in fact, is a relationship in trouble.

Public misunderstanding about the news business is partly responsible. The lamentations after the Torstar/Postmedia announcement, for instance, suggests that many Canadians don’t realize the extent to which the availability of local news is already compromised. While newspaper closings are not typically announced by the dozen, the reality is that the death knell has been sounding with disturbing regularity.

Hundreds of lost media outlets

The Local News Map, a crowd-sourced tool I created with Jon Corbett at the University of British Columbia to track changes to local news outlets across Canada, now displays 234 markers recording the loss of newspapers, broadcast outlets and digital news sites since 2008.

While the closings point to a broken business model — online advertising just doesn’t generate the dollars needed to support robust newsrooms — nearly half (48 per cent) of respondents in a recent pollhad not recently heard, read or seen anything about news organizations facing business or financial difficulties.

Online local news sites are emerging in some places to replace disappearing traditional news sources, but progress is slow and the future uncertain. To date, only 28 markers on the map indicate the launch of new digital sites. Another 13 document the demise of digital startups.

The relationship Canadians have with local news also suffers from complacency — never has it been so easy to access so much news.

A closer look, however, reveals that most of that news isn’t local. It also reveals that despite the dwindling number of subscribers, newspapers still play a key role in local political coverage. As the largest news operations in most communities, they report on stories that other news outlets ignore and their reporting sets the news agenda and influences the content produced by smaller competitors.

Newspapers cover more political news

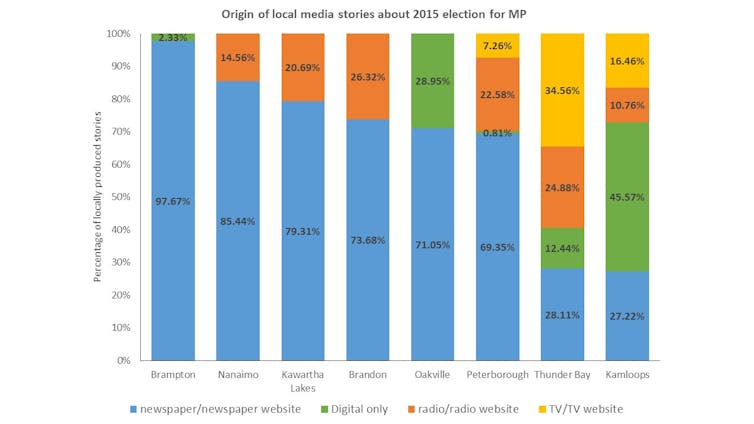

Research I conducted with Jaigris Hodson at Royal Roads University on how the races for local MPs were covered by respective local media during the 2015 federal election found that newspapers produced most of the stories in six of the eight places we studied.

In two of the communities, the post-election deterioration of the local news environment illustrates what’s lost when a news organization shuts down. The Nanaimo Daily News, the daily newspaper that generated almost half of all local reporting on the race to represent Nanaimo, B.C., ceased publication in January 2016. In Kamloops, B.C., where digital news sites dominated the local coverage, the NewsKamloops site closed on Sept. 30, 2016. It provided about a quarter of all reporting on the local race for MP in that community.

Deception has also frayed Canadians’ relationship with local news organizations. If they haven’t closed shop, most news outlets have slashed the number of newsroom employees and been less than transparent about the consequences.

When layoffs are announced — if they are announced — proprietors do not spell out which beats will no longer be covered or how many reporters are actually left running the operation. But they do expect loyal subscribers to keep subscribing and businesses to keep advertising.

The erosion in news coverage is gradual but over time it becomes apparent to all. Critics dismiss the local newspaper as fish wrap and suggest nobody will miss it when it’s gone. Those critics have a point.

Glimmers of hope?

The disappearance of timely, verified news means having to rely on the police department’s version of events in a police corruption scandal.

It means being vulnerable to fake news and propaganda from sketchy blogs and on Facebook produced by unknown authors with hidden agendas.

And it raises the spectre of greater polarization as substantive stories that explore issues, solutions and potential compromises are replaced by news briefs that summarize the opposing sides in black-and-white terms.

For all the misunderstanding, complacency and deception, however, there is reason to believe reconciliation is possible.

Multiple polls suggest Canadians still value local news, that at some level they recognize the role journalists play in holding power accountable, in building community by telling stories that people share and discuss, and in equipping citizens with the information they need to act collectively.

On the journalism side of things, innovators are emerging to meet the public’s local news needs.

Promising startups

The Sprawl, a crowd-funded pop-up digital news outlet launched in September to cover Calgary’s municipal election, took a break, and is now reporting on the city’s budget process.

Vancouver-based Discourse Media is inviting individuals to purchase $250 shares in the enterprise.

In Toronto, the West End Phoenix newspaper is pinning its survival on subscribers and generous patrons.

All of these startups have given up on the old advertising model and embraced new business strategies. But they still need money to survive.

And so we come to a final contributing factor to the dysfunctional relationship between Canadians and local news providers: One of the partners is a cheapskate used to getting something for nothing.

If we want accurate, up-to-date information about employment opportunities, health risks, problems in our schools, decisions made by city council and what to do during a natural disaster — good local journalism is the answer. But it doesn’t come cheap.

Whether it’s through donations, subscriptions or crowd-funded campaigns for specific investigations, we need to pay for it. Public declarations of love, devotion and commitment are much appreciated — but they don’t cover the bills.

This story was originally published by The Conversation, and is republished here with the author’s permission.